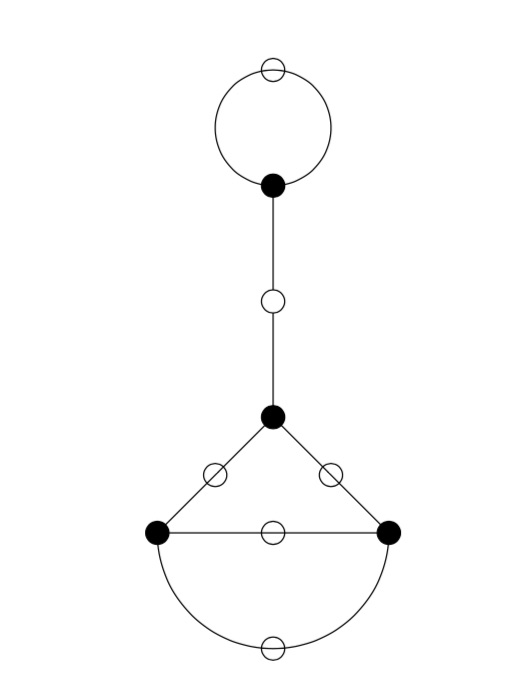

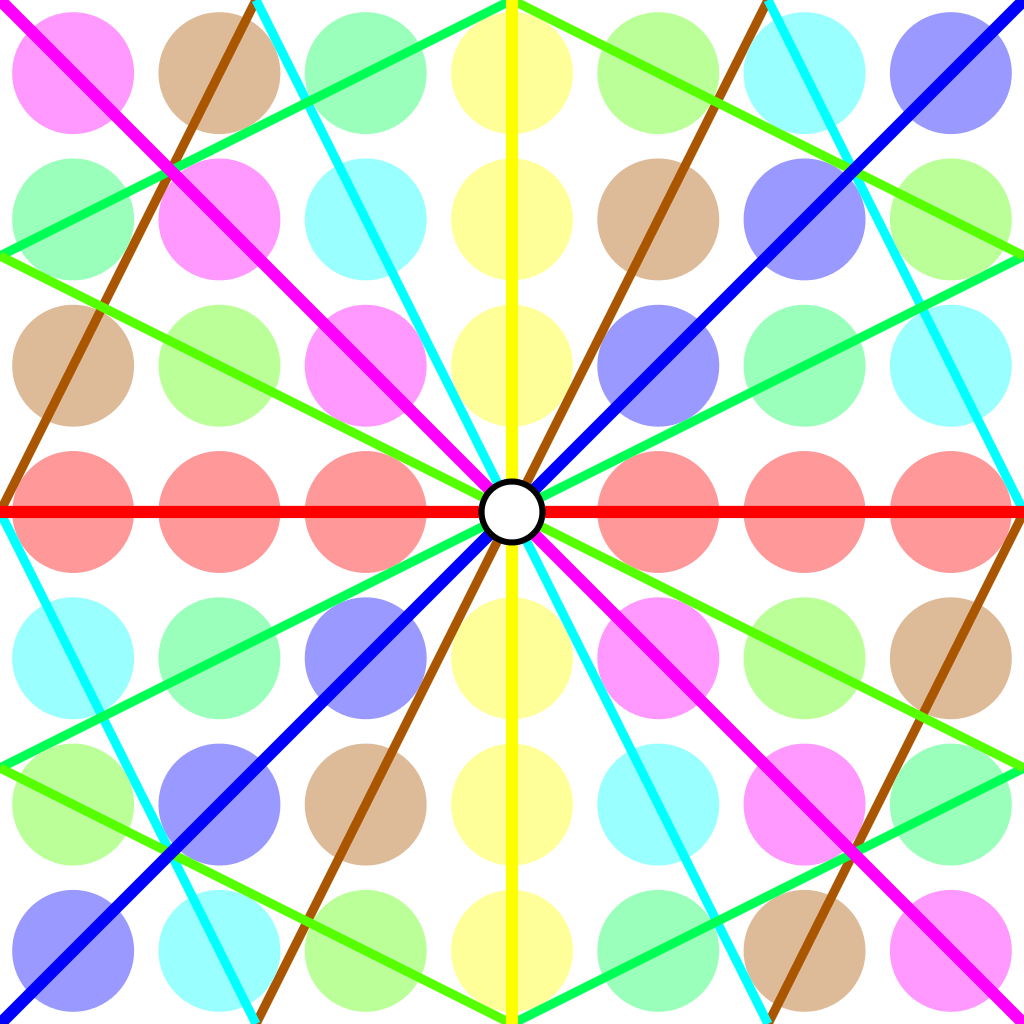

Whenever I visit someone’s YouTube or Twitter profile page, I hope to see an interesting banner image. Here’s the one from Richard Borcherds’ YouTube Channel.

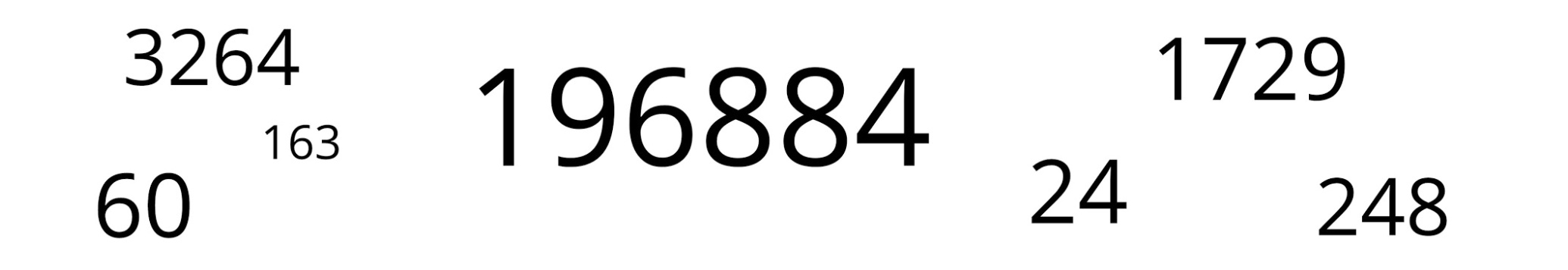

Not too surprisingly for Borcherds, almost all of these numbers are related to the monster group or its moonshine.

Let’s try to decode them, in no particular order.

196884

John McKay’s observation $196884 = 1 + 196883$ was the start of the whole ‘monstrous moonshine’ industry. Here, $1$ and $196883$ are the dimensions of the two smallest irreducible representations of the monster simple group, and $196884$ is the first non-trivial coefficient in Klein’s j-function in number theory.

$196884$ is also the dimension of the space in which Robert Griess constructed the Monster, following Simon Norton’s lead that there should be an algebra structure on the monster-representation of that dimension. This algebra is now known as the Griess algebra.

Here’s a recent talk by Griess “My life and times with the sporadic simple groups” in which he tells about his construction of the monster (relevant part starting at 1:15:53 into the movie).

1729

1729 is the second (and most famous) taxicab number. A long time ago I did write a post about the classic Ramanujan-Hardy story the taxicab curve (note to self: try to tidy up the layout of some old posts!).

Recently, connections between Ramanujan’s observation and K3-surfaces were discovered. Emory University has an enticing press release about this: Mathematicians find ‘magic key’ to drive Ramanujan’s taxi-cab number. The paper itself is here.

“We’ve found that Ramanujan actually discovered a K3 surface more than 30 years before others started studying K3 surfaces and they were even named. It turns out that Ramanujan’s work anticipated deep structures that have become fundamental objects in arithmetic geometry, number theory and physics.”

24

There’s no other number like $24$ responsible for the existence of sporadic simple groups.

24 is the length of the binary Golay code, with isomorphism group the sporadic Mathieu group $M_24$ and hence all of the other Mathieu-groups as subgroups.

24 is the dimension of the Leech lattice, with isomorphism group the Conway group $Co_0 = .0$ (dotto), giving us modulo its center the sporadic group $Co_1=.1$ and the other Conway groups $Co_2=.2, Co_3=.3$, and all other sporadics of the second generation in the happy family as subquotients (McL,HS,Suz and $HJ=J_2$)

24 is the central charge of the Monster vertex algebra constructed by Frenkel, Lepowski and Meurman. Most experts believe that the Monster’s reason of existence is that it is the symmetry group of this vertex algebra. John Conway was one among few others hoping for a nicer explanation, as he said in this interview with Alex Ryba.

24 is also an important number in monstrous moonshine, see for example the post the defining property of 24. There’s a lot more to say on this, but I’ll save it for another day.

60

60 is, of course, the order of the smallest non-Abelian simple group, $A_5$, the rotation symmetry group of the icosahedron. $A_5$ is the symmetry group of choice for most viruses but not the Corona-virus.

3264

3264 is the correct solution to Steiner’s conic problem asking for the number of conics in $\mathbb{P}^2_{\mathbb{C}}$ tangent to five given conics in general position.

Steiner himself claimed that there were $7776=6^5$ such conics, but realised later that he was wrong. The correct number was first given by Ernest de Jonquières in 1859, but a rigorous proof had to await the advent of modern intersection theory.

Eisenbud and Harris wrote a book on intersection theory in algebraic geometry, freely available online: 3264 and all that.

248

248 is the dimension of the exceptional simple Lie group $E_8$. $E_8$ is also connected to the monster group.

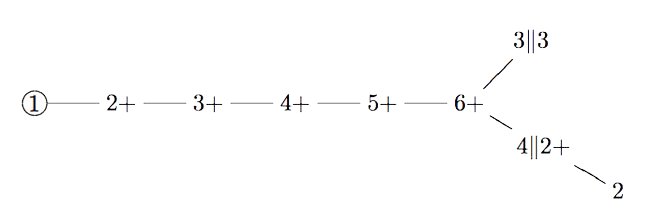

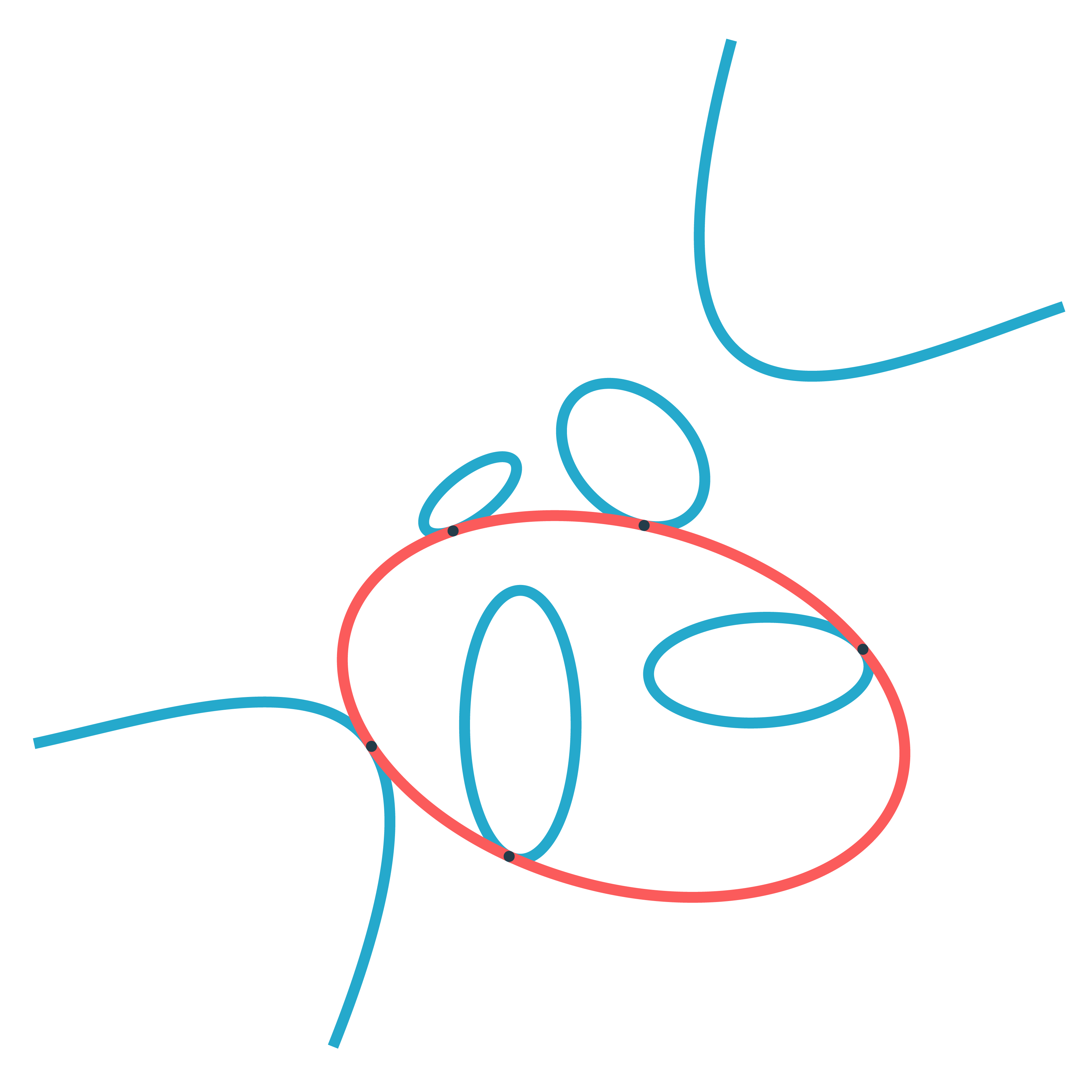

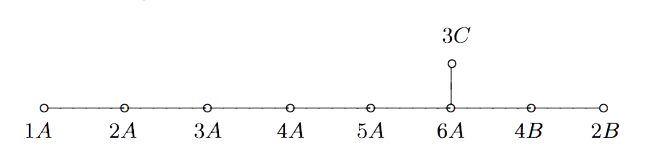

If you take two Fischer involutions in the monster (elements of conjugacy class 2A) and multiply them, the resulting element surprisingly belongs to one of just 9 conjugacy classes:

1A,2A,2B,3A,3C,4A,4B,5A or 6A

The orders of these elements are exactly the dimensions of the fundamental root for the extended $E_8$ Dynkin diagram.

This is yet another moonshine observation by John McKay and I wrote a couple of posts about it and about Duncan’s solution: the monster graph and McKay’s observation, and $E_8$ from moonshine groups.

163

163 is a remarkable number because of the ‘modular miracle’

\[

e^{\pi \sqrt{163}} = 262537412640768743.99999999999925… \]

This is somewhat related to moonshine, or at least to Klein’s j-function, which by a result of Kronecker’s detects the classnumber of imaginary quadratic fields $\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{-D})$ and produces integers if the classnumber is one (as is the case for $\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{-163})$).

The details are in the post the miracle of 163, or in the paper by John Stillwell, Modular Miracles, The American Mathematical Monthly, 108 (2001) 70-76.

Richard Borcherds, the math-vlogger, has an entertaining video about this story: MegaFavNumbers 262537412680768000

His description of the $j$-function (at 4:13 in the movie) is simply hilarious!

Borcherds connects $163$ to the monster moonshine via the $j$-function, but there’s another one.

The monster group has $194$ conjugacy classes and monstrous moonshine assigns a ‘moonshine function’ to each conjugacy class (the $j$-function is assigned to the identity element). However, these $194$ functions are not linearly independent and the space spanned by them has dimension exactly $163$.

One Comment