Dedekind’s Psi-function $\Psi(n)= n \prod_{p |n}(1 + \frac{1}{p})$ pops up in a number of topics:

- $\Psi(n)$ is the index of the congruence subgroup $\Gamma_0(n)$ in the modular group $\Gamma=PSL_2(\mathbb{Z})$,

- $\Psi(n)$ is the number of points in the projective line $\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/n\mathbb{Z})$,

- $\Psi(n)$ is the number of classes of $2$-dimensional lattices $L_{M \frac{g}{h}}$ at hyperdistance $n$ in Conway’s big picture from the standard lattice $L_1$,

- $\Psi(n)$ is the number of admissible maximal commuting sets of operators in the Pauli group of a single qudit.

The first and third interpretation have obvious connections with Monstrous Moonshine.

Conway’s big picture originated from the desire to better understand the Moonshine groups, and Ogg’s Jack Daniels problem

asks for a conceptual interpretation of the fact that the prime numbers such that $\Gamma_0(p)^+$ is a genus zero group are exactly the prime divisors of the order of the Monster simple group.

Here’s a nice talk by Ken Ono : Can’t you just feel the Moonshine?

For this reason it might be worthwhile to make the connection between these two concepts and the number of points of $\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/n\mathbb{Z})$ as explicit as possible.

Surely all of this is classical, but it is nicely summarised in the paper by Tatitscheff, He and McKay “Cusps, congruence groups and monstrous dessins”.

The ‘monstrous dessins’ from their title refers to the fact that the lattices $L_{M \frac{g}{h}}$ at hyperdistance $n$ from $L_1$ are permuted by the action of the modular groups and so determine a Grothendieck’s dessin d’enfant. In this paper they describe the dessins corresponding to the $15$ genus zero congruence subgroups $\Gamma_0(n)$, that is when $n=1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,12,13,16,18$ or $25$.

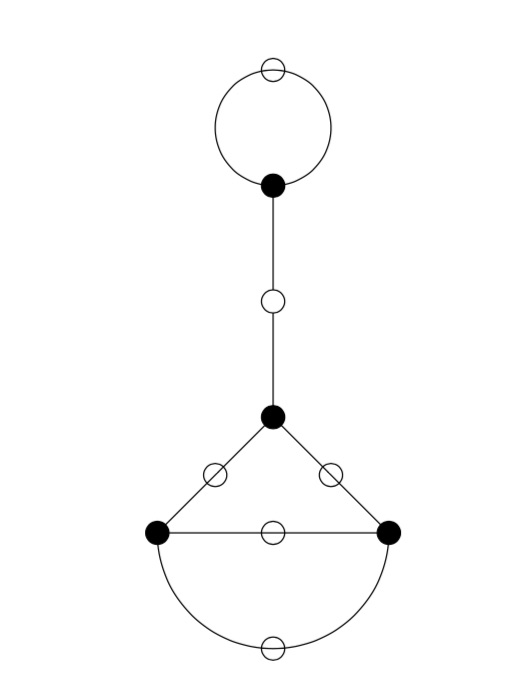

Here’s the ‘monstrous dessin’ for $\Gamma_0(6)$

But, one can compute these dessins for arbitrary $n$, describing the ripples in Conway’s big picture, and try to figure out whether they are consistent with the Riemann hypothesis.

We will get there eventually, but let’s start at an easy pace and try to describe the points of the projective line $\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z})$.

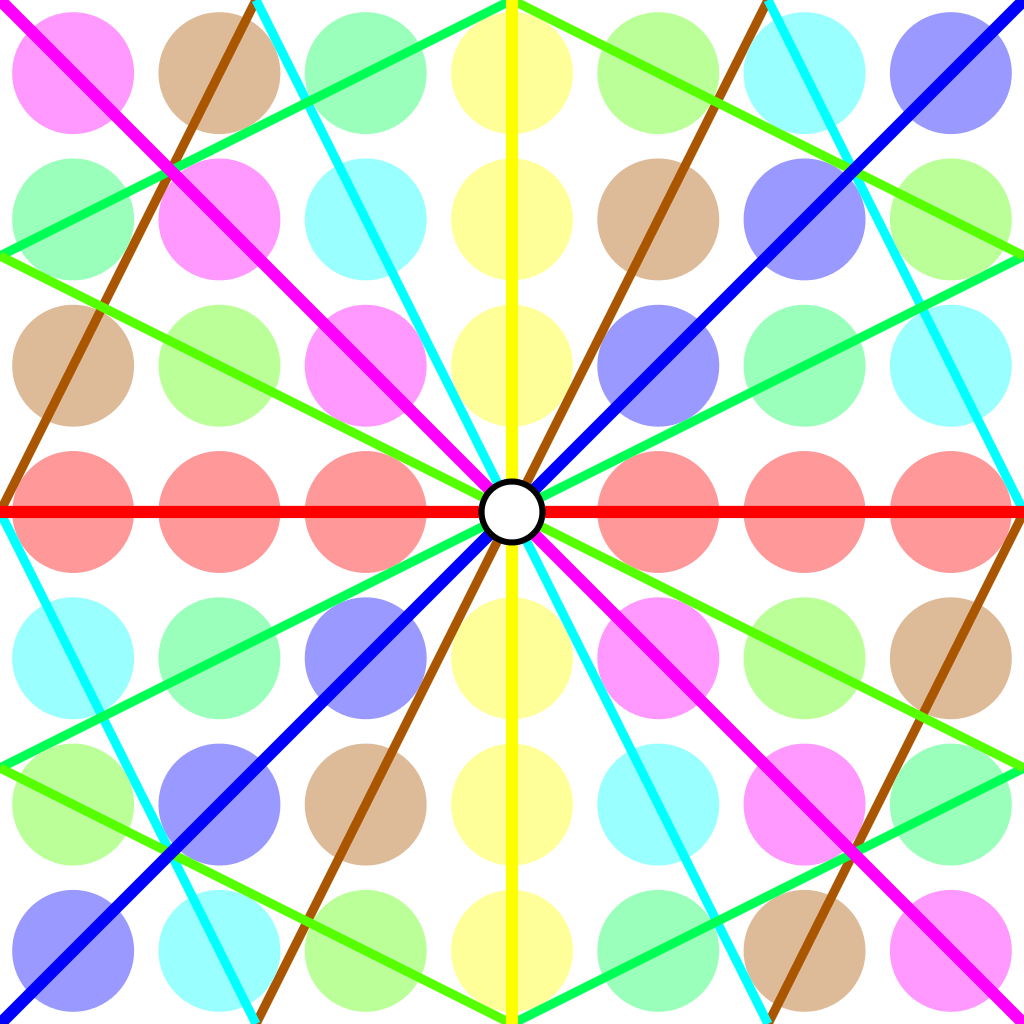

Over a field $k$ the points of $\mathbb{P}^1(k)$ correspond to the lines through the origin in the affine plane $\mathbb{A}^2(k)$ and they can represented by projective coordinates $[a:b]$ which are equivalence classes of couples $(a,b) \in k^2- \{ (0,0) \}$ under scalar multiplication with non-zero elements in $k$, so with points $[a:1]$ for all $a \in k$ together with the point at infinity $[1:0]$. When $n=p$ is a prime number we have $\# \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}) = p+1$. Here are the $8$ lines through the origin in $\mathbb{A}^2(\mathbb{Z}/7\mathbb{Z})$

Over an arbitrary (commutative) ring $R$ the points of $\mathbb{P}^1(R)$ again represent equivalence classes, this time of pairs

\[

(a,b) \in R^2~:~aR+bR=R \]

with respect to scalar multiplication by units in $R$, that is

\[

(a,b) \sim (c,d)~\quad~\text{iff}~\qquad \exists \lambda \in R^*~:~a=\lambda c, b = \lambda d \]

For $\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z})$ we have to find all pairs of integers $(a,b) \in \mathbb{Z}^2$ with $0 \leq a,b < n$ with $gcd(a,b)=1$ and use Cremona’s trick to test for equivalence:

\[

(a,b) = (c,d) \in \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z})~\quad \text{iff}~\quad ad-bc \equiv 0~mod~n \]

The problem is to find a canonical representative in each class in an efficient way because this is used a huge number of times in working with modular symbols.

Perhaps the best algorithm, for large $n$, is sketched in pages 145-146 of Bill Stein’s Modular forms: a computational approach.

For small $n$ the algorithm in $\S 1.3$ in the Tatitscheff, He and McKay paper suffices:

- Consider the action of $(\mathbb{Z}/n\mathbb{Z})^*$ on $\{ 0,1,…,n-1 \}=\mathbb{Z}/n\mathbb{Z}$ and let $D$ be the set of the smallest elements in each orbit,

- For each $d \in D$ compute the stabilizer subgroup $G_d$ for this action and let $C_d$ be the set of smallest elements in each $G_d$-orbit on the set of all elements in $\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z}$ coprime with $d$,

- Then $\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/n\mathbb{Z})= \{ [c:d]~|~d \in D, c \in C_d \}$.

Let’s work this out for $n=12$ which will be our running example (the smallest non-squarefree non-primepower):

- $(\mathbb{Z}/12\mathbb{Z})^* = \{ 1,5,7,11 \} \simeq C_2 \times C_2$,

- The orbits on $\{ 0,1,…,11 \}$ are

\[

\{ 0 \}, \{ 1,5,7,11 \}, \{ 2,10 \}, \{ 3,9 \}, \{ 4,8 \}, \{ 6 \} \]

and $D=\{ 0,1,2,3,4,6 \}$, - $G_0 = C_2 \times C_2$, $G_1 = \{ 1 \}$, $G_2 = \{ 1,7 \}$, $G_3 = \{ 1,5 \}$, $G_4=\{ 1,7 \}$ and $G_6=C_2 \times C_2$,

- $1$ is the only number coprime with $0$, giving us $[1:0]$,

- $\{ 0,1,…,11 \}$ are all coprime with $1$, and we have trivial stabilizer, giving us the points $[0:1],[1:1],…,[11:1]$,

- $\{ 1,3,5,7,9,11 \}$ are coprime with $2$ and under the action of $\{ 1,7 \}$ they split into the orbits

\[

\{ 1,7 \},~\{ 3,9 \},~\{ 5,11 \} \]

giving us the points $[1:2],[3:2]$ and $[5:2]$, - $\{ 1,2,4,5,7,8,10,11 \}$ are coprime with $3$, the action of $\{ 1,5 \}$ gives us the orbits

\[

\{ 1,5 \},~\{ 2,10 \},~\{ 4,8 \},~\{ 7,11 \} \]

and additional points $[1:3],[2:3],[4:3]$ and $[7:3]$, - $\{ 1,3,5,7,9,11 \}$ are coprime with $4$ and under the action of $\{ 1,7 \}$ we get orbits

\[

\{ 1,7 \},~\{ 3,9 \},~\{ 5,11 \} \]

and points $[1:4],[3:4]$ and $[5,4]$, - Finally, $\{ 1,5,7,11 \}$ are the only coprimes with $6$ and they form a single orbit under $C_2 \times C_2$ giving us just one additional point $[1:6]$.

This gives us all $24= \Psi(12)$ points of $\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/12 \mathbb{Z})$ (strangely, op page 43 of the T-H-M paper they use different representants).

One way to see that $\# \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z}) = \Psi(n)$ comes from a consequence of the Chinese Remainder Theorem that for the prime factorization $n = p_1^{e_1} … p_k^{e_k}$ we have

\[

\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z}) = \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/p_1^{e_1} \mathbb{Z}) \times … \times \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/p_k^{e_k} \mathbb{Z}) \]

and for a prime power $p^k$ we have canonical representants for $\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/p^k \mathbb{Z})$

\[

[a:1]~\text{for}~a=0,1,…,p^k-1~\quad \text{and} \quad [1:b]~\text{for}~b=0,p,2p,3p,…,p^k-p \]

which shows that $\# \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/p^k \mathbb{Z}) = (p+1)p^{k-1}= \Psi(p^k)$.

Next time, we’ll connect $\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z})$ to Conway’s big picture and the congruence subgroup $\Gamma_0(n)$.

Comments