In 1982, the BBC ran a series of 10 weekly programmes entitled de Bono’s Thinking Course. In the book accompanying the series Edward de Bono recalls the origin of his ‘L-Game’:

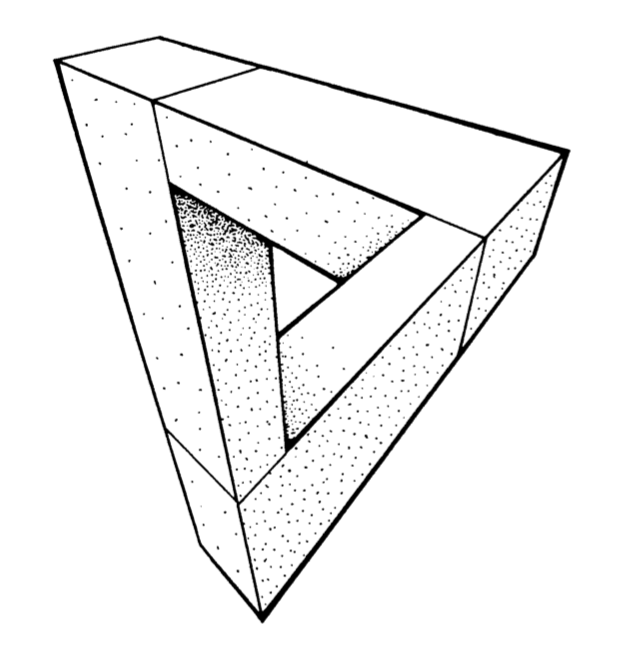

Many years ago I was sitting next to the famous mathematician, Professor Littlewood, at dinner in Trinity College. We were talking about getting computers to play chess. We agreed that chess was difficult because of the large number of pieces and different moves. It seemed an interesting challenge to design a game that was as simple as possible and yet could be played with a degree of skill.

As a result of that challenge I designed the ‘L-Game’, in which each player has only one piece (the L-shape piece). In turn he moves this to any new vacant position (lifting up, turning over, moving across the board to a vacant position, etc.). After moving his L-piece he can – if he wishes – move either one of the small neutral pieces to any new position. The object of the game is to block your opponent’s L-shape so that no move is open to it.

It is a pleasant exercise in symmetry to calculate the number of possible L-game positions.

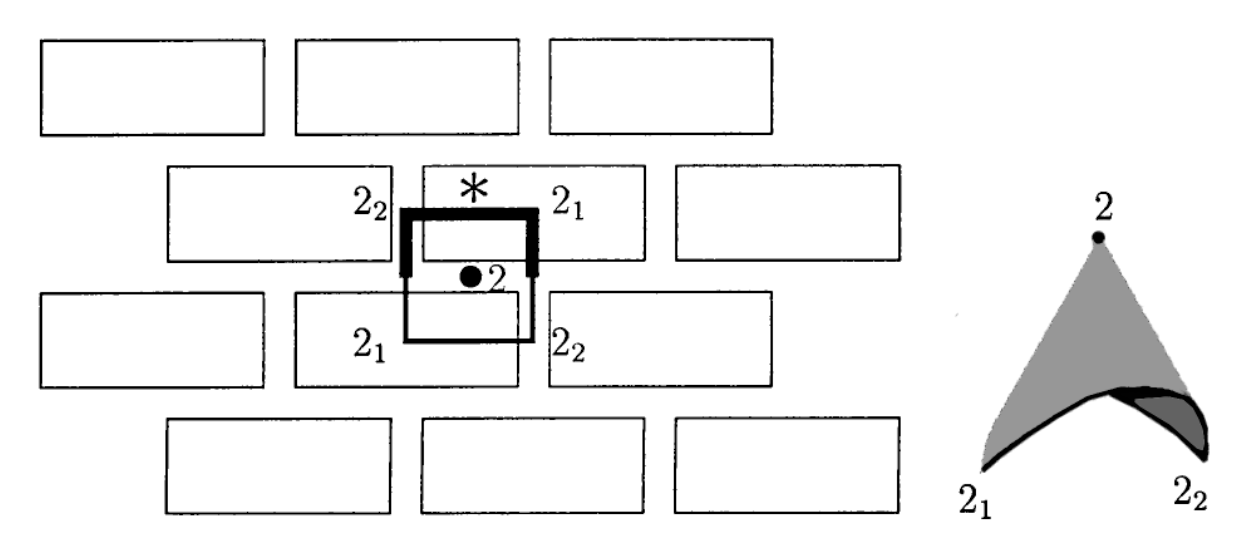

The $4 \times 4$ grid has $8$ symmetries, making up the dihedral group $D_8$: $4$ rotations and $4$ reflections.

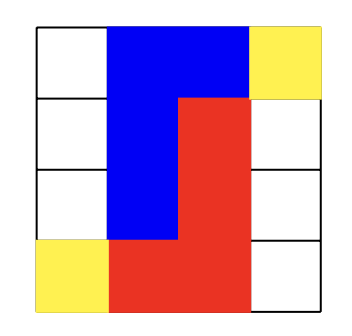

An L-piece breaks all these symmetries, that is, it changes in form under each of these eight operations. That is, using the symmetries of the $4 \times 4$-grid we can put one of the L-pieces (say the Red one) on the grid as a genuine L, and there are exactly 6 possibilities to do so.

For each of these six positions one can then determine the number of possible placings of the Blue L-piece. This is best done separately for each of the 8 different shapes of that L-piece.

Here are the numbers when the red L is placed in the left bottom corner:

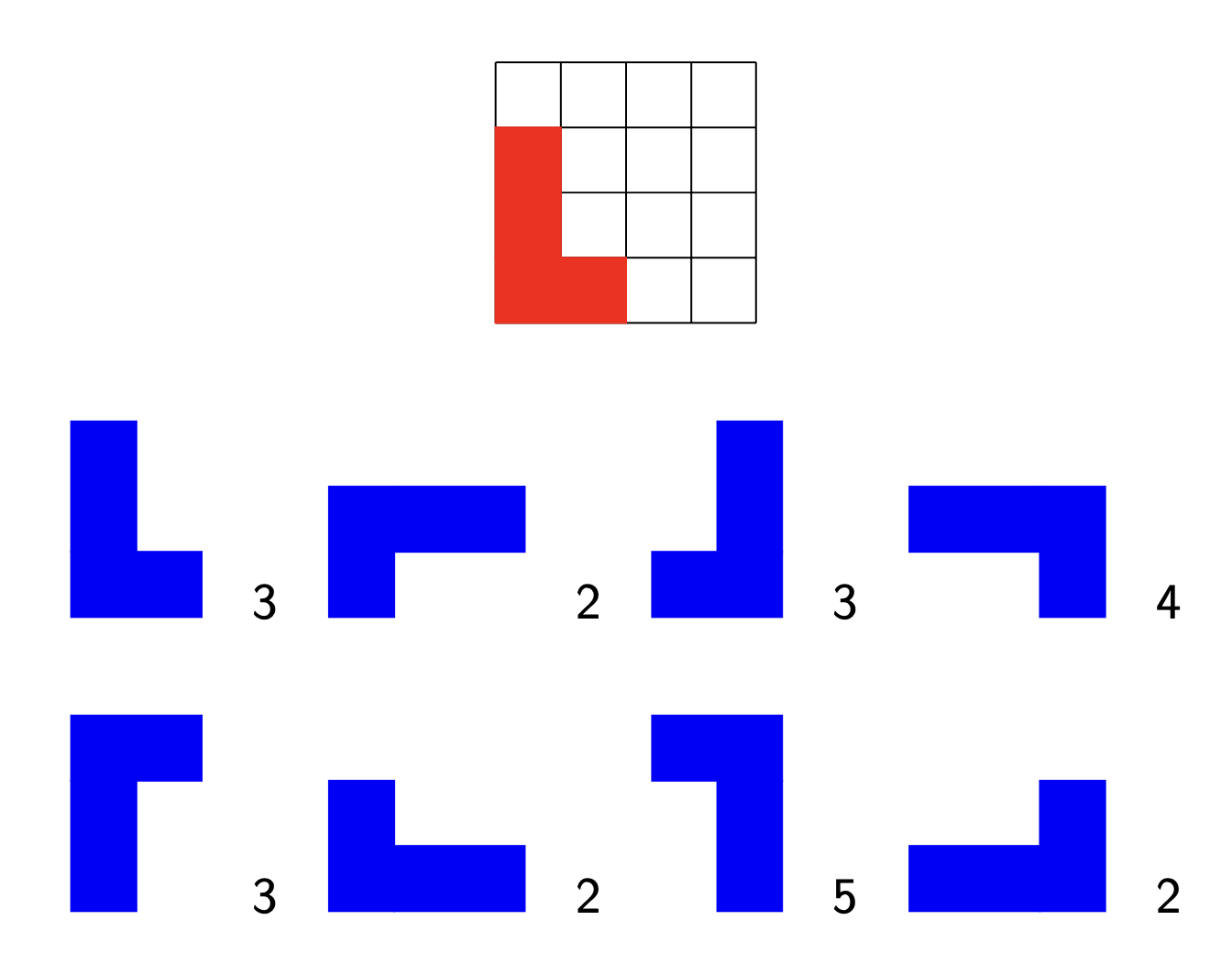

In total there are thus 24 possibilities to place the Blue L-piece in that case. We can repeat the same procedure for the remaining Red L-positions. Here are the number of possibilities for Blue in each case:

That is, there are 82 possibilities to place the two L-pieces if the Red one stands as a genuine L on the board.

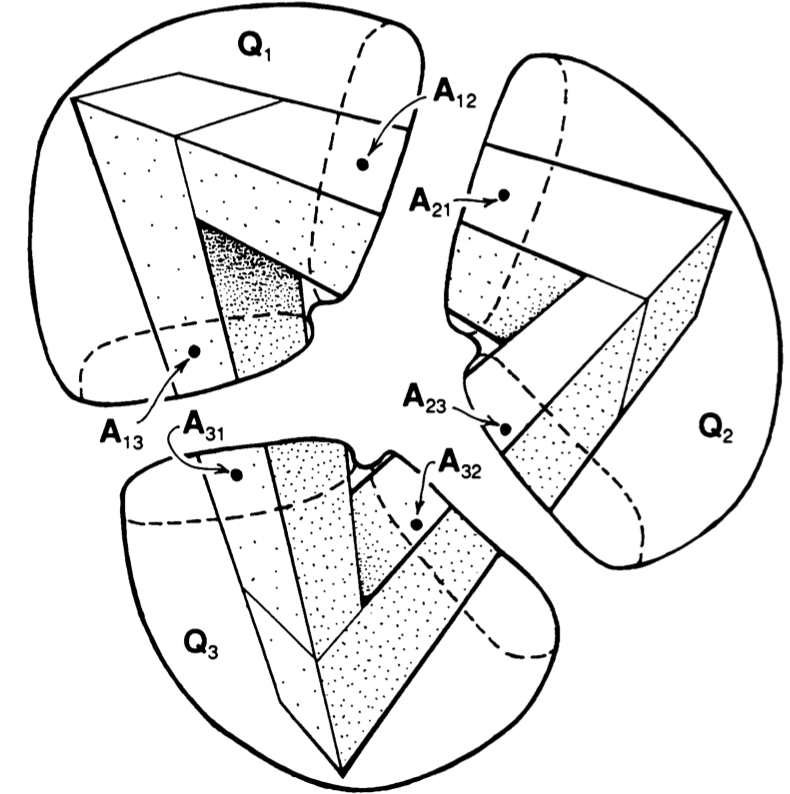

But then, the L-game has exactly $18368 = 8 \times 82 \times 28$ different positions, where the factor

- $8$ gives the number of symmetries of the square $4 \times 4$ grid.

- Using these symmetries we can put the Red L-piece on the grid as a genuine $L$ and we just saw that this leaves $82$ possibilities for the Blue L-piece.

- This leaves $8$ empty squares and so $28 = \binom{8}{2}$ different choices to place the remaining two neutral pieces.

The $2296 = 82 \times 28$ positions in which the red L-piece is placed as a genuine L can then be analysed by computer and the outcome is summarised in Winning Ways 2 pages 384-386 (with extras on pages 408-409).

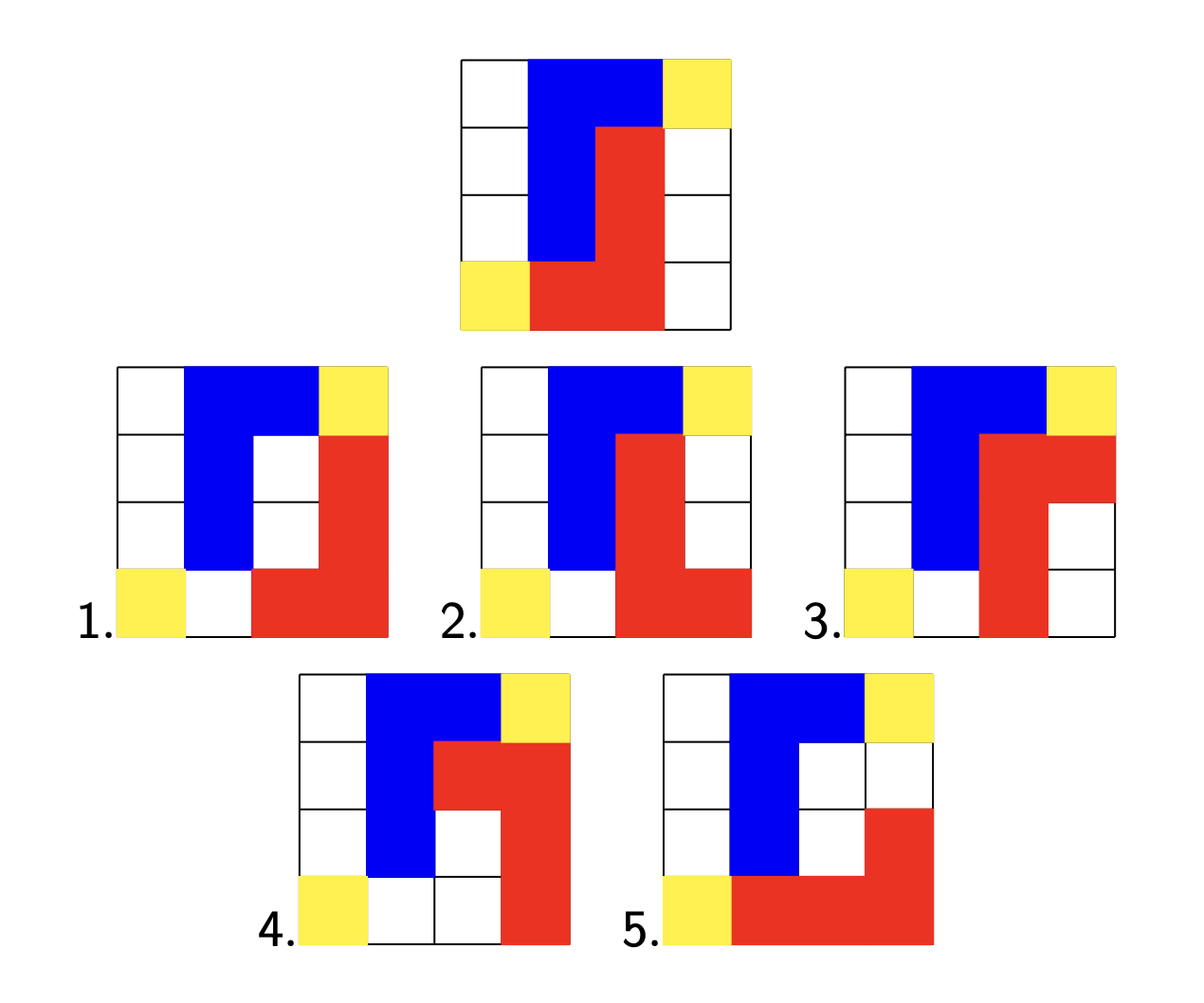

Of the $2296$ positions only $29$ are $\mathcal{P}$-positions, meaning that the next player (Red) will loose. Here are these winning positions for Blue

Here, neutral piece(s) should be put on the yellow square(s). A (potential) remaining neutral piece should be placed on one of the coloured squares. The different colours indicate the remoteness of the $\mathcal{P}$-position:

- Pink means remoteness $0$, that is, Red has no move whatsoever, so mate in $0$.

- Orange means remoteness $2$: Red still has a move, but will be mated after Blue’s next move.

- Purple stands for remoteness $4$, that is, Blue mates Red in $4$ moves, Red starting.

- Violet means remoteness $6$, so Blue has a mate in $6$ with Red starting

- Olive stands for remoteness $8$: Blue mates within eight moves.

Memorising these gives you a method to spot winning opportunities. After Red’s move image a board symmetry such that Red’s piece is a genuine L, check whether you can place your Blue piece and one of the yellow pieces to obtain one of the 29 $\mathcal{P}$-positions, and apply the reverse symmetry to place your piece.

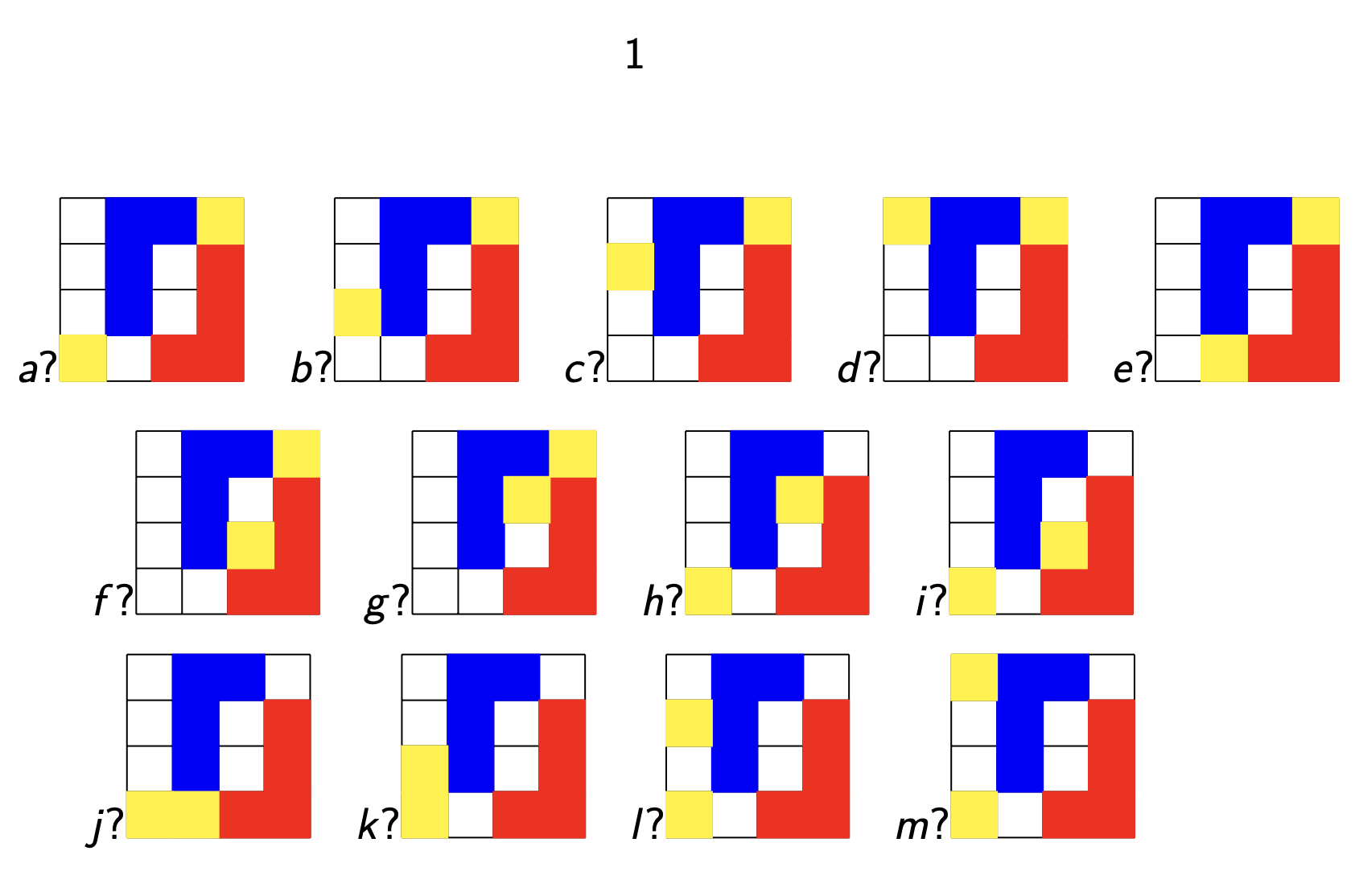

If you don’t know this, you can run into trouble very quickly. From the starting position, Red has five options to place his L-piece before moving one of the two yellow counters.

All possible positions of the first option loose immediately.

For example in positions $a,b,c,d,f$ and $l$, Blue wins by playing

Here’s my first attempt at an opening repertoire for the L-game. Question mark means immediate loss, question mark with a number means mate after that number of moves, x means your opponent plays a sensible strategy.

Surely I missed cases, and made errors in others. Please leave corrections in the comments and I’ll try to update the positions.

One Comment