After the death of Grothendieck in November 2014, about 30.000 pages of his writings were found in Lasserre.

Since then I’ve been trying to follow what happened to them:

- Where are Grothendieck’s writings?

- Where are Grothendieck’s writings? (2)

- Grothendieck’s gribouillis

- Grothendieck’s gribouillis (2)

- Grothendieck’s gribouillis (3)

- Grothendieck’s gribouillis (4)

- Grothendieck’s gribouillis (5)

So, what’s new?

Well, finally we have closure!

Last Friday, Grothendieck’s children donated the 30.000 Laserre pages to the Bibliotheque Nationale de France.

Via Des manuscrits inédits du génie des maths Grothendieck entrent à la BnF (and Google-translate):

“The singularity of these manuscripts is that they “cover many areas at the same time” to form “a whole, a + cathedral work +, with undeniable literary qualities”, analyzes Jocelyn Monchamp, curator in the manuscripts department of the BnF.

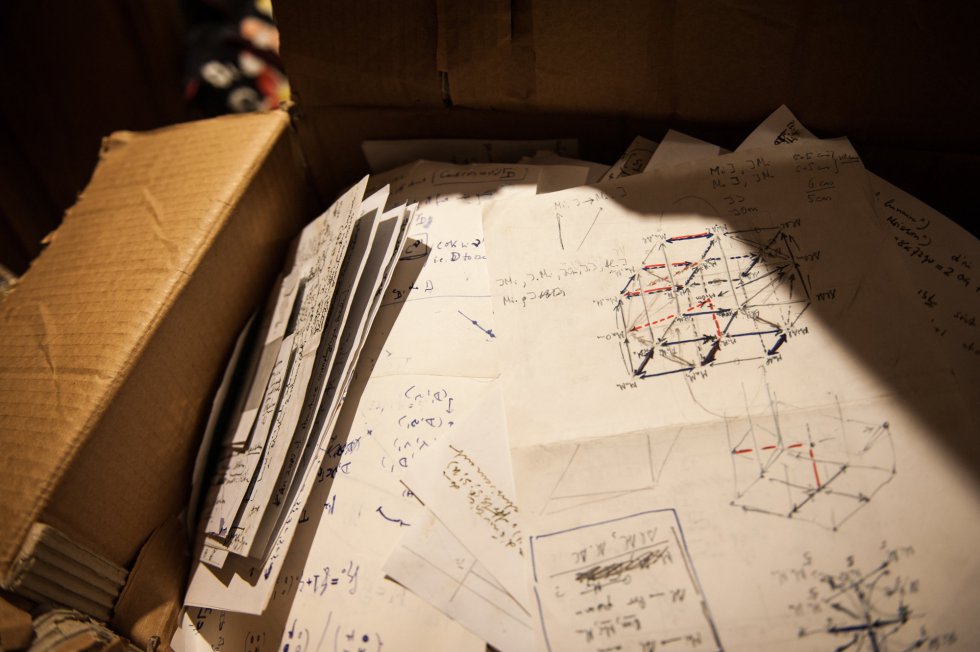

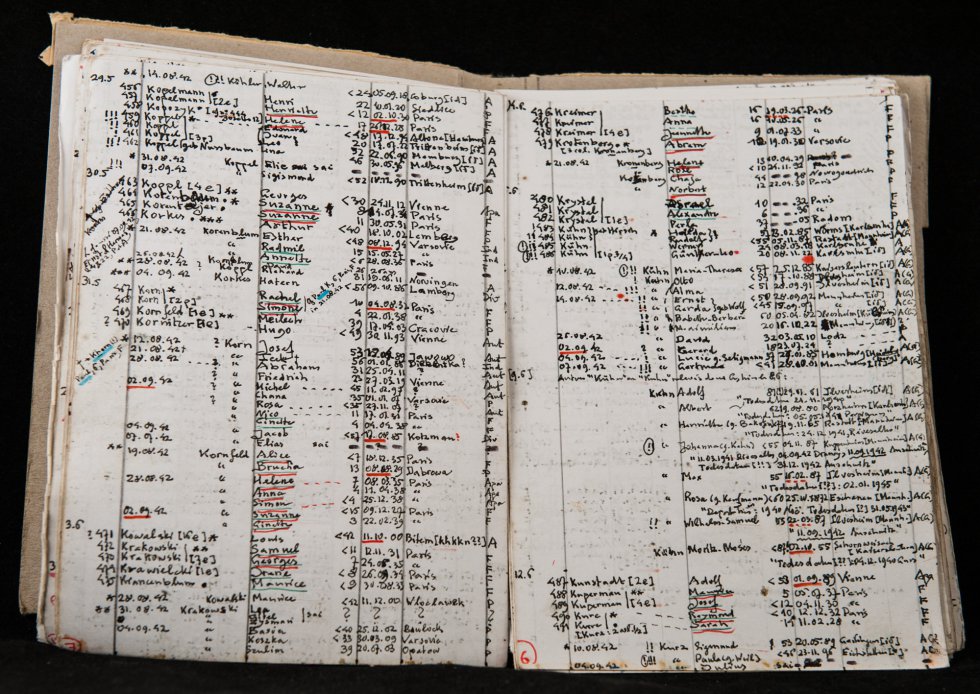

More than in “Récoltes et semailles”, very autobiographical, the author is “in a metaphysical retreat”, explains the curator, who has been going through the texts with passion for a month. A long-term task as the writing, in fountain pen, is dense and difficult to decipher. “I got used to it… And the advantage for us was that the author had methodically paginated and dated the texts.” One of the parts, entitled “Structures of the psyche”, a book of enigmatic diagrams translating psychology into algebraic language. In another, “The Problem of Evil”, he unfolds over 15,000 pages metaphysical meditations and thoughts on Satan. We sense a man “caught up by the ghosts of his past”, with an adolescence marked by the Shoah, underlines Johanna Grothendieck whose grandfather, a Russian Jew who fled Germany during the war, died at Auschwitz.

The deciphering work will take a long time to understand everything this genius wanted to say.

On Friday, the collection joined the manuscripts department of the Richelieu site, the historic cradle of the BnF, alongside the writings of Pierre and Marie Curie and Louis Pasteur. It will only be viewable by researchers.“This is a unique testimony in the history of science in the 20th century, of major importance for research,” believes Jocelyn Monchamp.

During the ceremony, one of the volumes was placed in a glass case next to a manuscript by the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid.”

Probably, the recent publication of Récoltes et Semailles clinched the deal.

Also, it is unclear at this moment whether the Istituto Grothendieck, which harbours The centre for Grothendieck studies coordinated by Mateo Carmona (see this post) played a role in the decision making, nor what role the Centre will play in the further studies of Grothendieck’s gribouillis.

For other coverage on this, see Hermit ‘scribblings’ of eccentric French math genius unveiled.

3 Comments