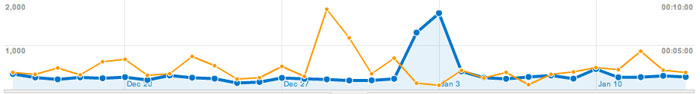

Sunday january 2nd around 18hr NeB-stats went crazy.

Referrals clarified that the post ‘What is the knot associated to a prime?’ was picked up at Reddit/math and remained nr.1 for about a day.

Now, the dust has settled, so let’s learn from the experience.

A Reddit-mention is to a blog what doping is to a sporter.

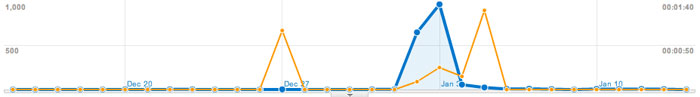

You get an immediate boost in the most competitive of all blog-stats, the number of unique vistors (blue graph), but is doesn’t result in a long-term effect, and, it may even be harmful to more essential blog-stats, such as the average time visitors spend on your site (yellow graph).

For NeB the unique vistors/day fluctuate normally around 300, but peaked to 1295 and 1733 on the ‘Reddit-days’. In contrast, the avg. time on site is normally around 3 minutes, but dropped the same days to 44 and 30 seconds!

Whereas some of the Reddits spend enough time to read the post and comment on it, the vast majority zap from one link to the next. Having monitored the Reddit/math page for two weeks, I’m convinced that post only made it because it was visually pretty good. The average Reddit/math-er is a viewer more than a reader…

So, should I go for shorter, snappier, more visual posts?

Let’s compare Reddits to those coming from the three sites giving NeB most referrals : Google search, MathOverflow and Wikipedia.

This is the traffic coming from Reddit/math, as always the blue graph are the unique visitors, the yellow graph their average time on site, blue-scales to the left, yellow-scales to the right.

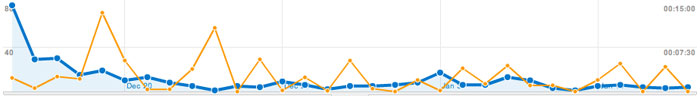

Here’s the same graph for Google search. The unique visitors/day fluctuate around 50 and their average time on site about 2 minutes.

The math-related search terms most used were this month : ‘functor of point approach’, ‘profinite integers’ and ‘bost-connes sytem’.

More rewarding to me are referrals from MathOverflow.

The number of visitors depends on whether the MathO-questions made it to the front-page (for example, the 80 visits on december 15, came from the What are dessins d’enfants?-topic getting an extra comment that very day, and having two references to NeB-posts : The best rejected proposal ever and Klein’s dessins d’enfant and the buckyball), but even older MathO-topics give a few referrals a day, and these people sure take their time reading the posts (+ 5 minutes).

Other MathO-topics giving referrals this month were Most intricate and most beautiful structures in mathematics (linking to Looking for F-un), What should be learned in a first serious schemes course? (linking to Mumford’s treasure map (btw. one of the most visited NeB-posts ever)), How much of scheme theory can you visualize? (linking again to Mumford’s treasure map) and Approaches to Riemann hypothesis using methods outside number theory (linking to the Bost-Connes series).

Finally, there’s Wikipedia

giving 5 to 10 referrals a day, with a pretty good time-on-site average (around 4 minutes, peaking to 12 minutes). It is rewarding to see NeB-posts referred to in as diverse Wikipedia-topics as ‘Fifteen puzzle’, ‘Field with one element’, ‘Evariste Galois’, ‘ADE classification’, ‘Monster group’, ‘Arithmetic topology’, ‘Dessin d’enfant’, ‘Groupoid’, ‘Belyi’s theorem’, ‘Modular group’, ‘Cubic surface’, ‘Esquisse d’un programme’, ‘N-puzzle’, ‘Shabat polynomial’ and ‘Mathieu group’.

What lesson should be learned from all this data? Should I go for shorter, snappier and more visual posts, or should I focus on the small group of visitors taking their time reading through a longer post, and don’t care about the appallingly high bounce rate the others cause?

8 Comments