Sooner or later, every generation of Bourbakistas is drawn to the natural beauty of the Auvergne-region, known for its mountain ranges and dormant volcanoes.

In the summer of 1935 the founding fathers created Nicolas Bourbaki during their congress in Besse-en-Chandesse.

Standing from left to right: Cartan, de Possel, Dieudonne, Weil and a local technician. Seated from left to right: Mirles (guinea pig), Chevalley and Mandelbrojt.

In August 1954, the remaining founding fathers gathered with second generation Bourbakistas and a bunch of guests at the Hotel des Pins in Murol.

Apart from Cartan, Chevalley, Delsarte, Dieudonne and Weil, present were of the second generation: Dixmier, Godement, Koszul, Eilenberg, Samuel, Schwartz and Serre. There was a guinea-pig (Serge Lang), an ‘efficiency expert’ (Saunders MacLane), two ‘foreign visitors’ (Hochschild and John Tate) and two ‘honorable foreign visitors’ (Iyanaga and Kosaku Yosida).

From left to right, Godement, Dieudonne, Weil, MacLane, and a smug looking Serre (he knew he would be awarded a Fields medal at the coming ICM in a few days time).

For the third generation, the Auvergne-spot of choice was Aumont-Aubrac, now part of Peyre en Aubrac. In Occitan Aumont-Aubrac is called Autmont from the Latin ‘altum montem’, haute montagne (high mountain), appropriate as the average elevation of the commune is 1045m.

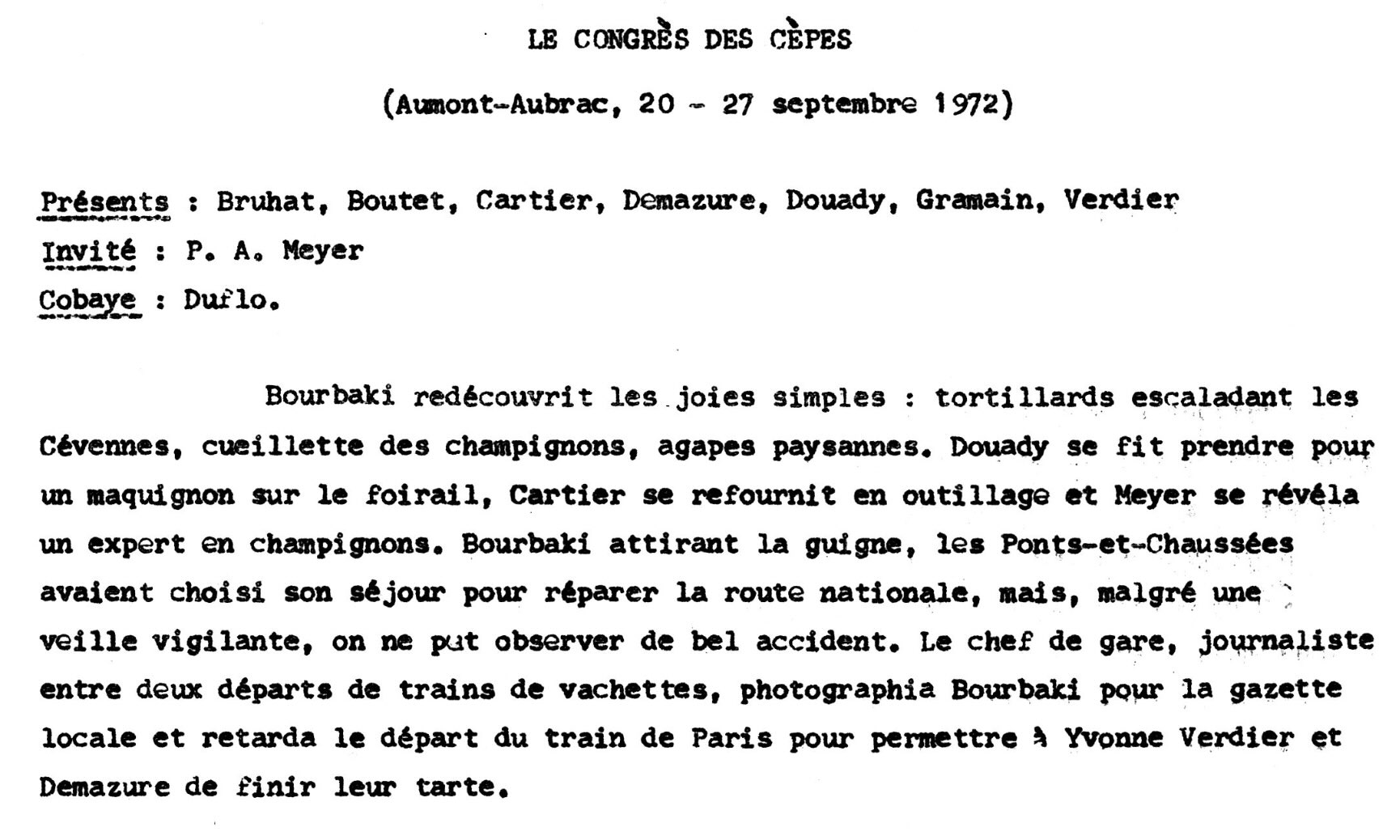

‘Tribu 86’ recounts their visit in the fall of 1972, and calls it ‘Le congres des cèpes‘ (the Porcini mushrooms congress).

Bourbaki rediscovered the simple joys: slow-moving trains climbing the Cévennes, mushroom picking, peasant feasts. Douady was mistaken for a horse dealer at the fairground, Cartier was restocking his tools, and Meyer revealed himself to be a mushroom expert.

Bourbaki attracted bad luck; the Ponts-et-Chaussées had chosen his stay to repair the main road, but, despite vigilant monitoring, no notable accidents were observed. The stationmaster, a journalist between two train departures, photographed Bourbaki for the local gazette, and delayed the departure of the train for Paris to allow Yvonne Verdier and Demazure to finish their pie.

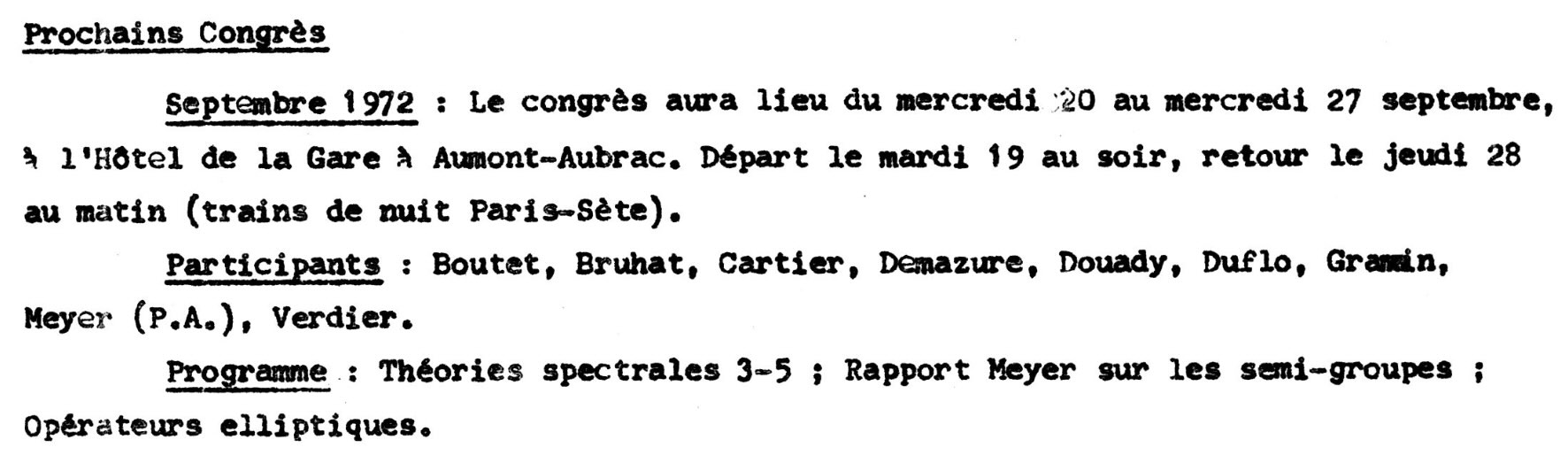

From ‘Tribu 85’ we learn that they stayed in ‘Hotel de la Gare’, and arrived by night-train from Paris.

The ‘Grand Hotel de la Gare’ aka ‘Grand Hotel Prouheze’ was run by the Prouheze family but is now closed.

‘Tribu 85’, which is the account of their previous summer congress in Cabris (called ‘The water congress’) contains:

The sky took it upon itself to suggest the title of the conference; one rarely sees so much rain at La Messuguière, perhaps to mourn its impending closure.

Perhaps it was due to the bad weather at Cabris last time, or the fear of unavailability of their favourite ‘Villa La Messuguière’, or their enjoyable stay at Aumont-Aubrac in the fall of 1972, anyway Bourbaki decided to have their summer 1973 congress again in Aumont-Aubrac, and again at the Hotel de la Gare (as we can learn from La Tribu 87).

A large group gathered on the evening of June 5th 1973, this time with their bicycles, to take the night train from Paris to Aumont-Aubrac: Hyman Bass, Louis Boutet de Monvel, François Bruhat, Pierre Cartier, Michel Demazure, Adrien Douady (with his wife Regine), André Gramain, Barry Mazur (with his wife Gretchen and their son Zeke), Michel Raynaud, Jean-Louis Verdier, and Jean-Marc Fontaine (with his wife Laurence).

Determined to get to know the real country in the absence of the p-adic country, Bourbaki returned a second time to his Auvergnian roots (Besse 1935!).

Thanks to the organisational progress of the SNCF, which now runs sleeper bike trains, and to the Fontaines who brought their car, Bourbaki did not lack means of transportation. They were necessary to ensure the connection between Bourbaki’s two bases.

Le Moulin, four kilometers from Aumont, increasingly better equipped, allowed for serious discussions to alternate with the sounds of bourrée and the sipping of lemonade and beer. A large fire chased away evil spirits and the threat of colds.

Bourbaki, ever the genius, chose as his base the pigs’ den, where he had ten thousand hectares of flowering and fragrant meadows.

‘Le Moulin’, Bourbaki’s ‘second base’ in the country is now the Chambres d’Hotes au Moulin du Chambon and lies indeed 4km from Aumont-Aubrac, and has indeed a large fireplace, a nice cantou.

Back then, it probably was a pub and the endpoint of several afternoon bicycle excursions for the Bourbakis.

The high point of the congress was their bicycle ‘tour du Gevaudan’. The Gevaudan is the old name of what is now the Lozère département. The name was derived from the Gabali, a Gallic tribe.

Today, the name Gevaudan lives on in the story of the beast of Gevaudan, which killed between 82 and 124 people between June 30, 1764 to June 19, 1767. There’s a statue of the beast in front of the Hotel-de-Ville in Aumont-Abrac.

Previously in this series

Comments closed