I told you six months ago that I’ll be out of my office by the end of summer and will no longer have access to the webserver running this blog.

There’s a slight possibility that the new inhabitant is willing to inherit said iMac and as long as (s)he doesn’t shut it down, this site may be online for a few extra months.

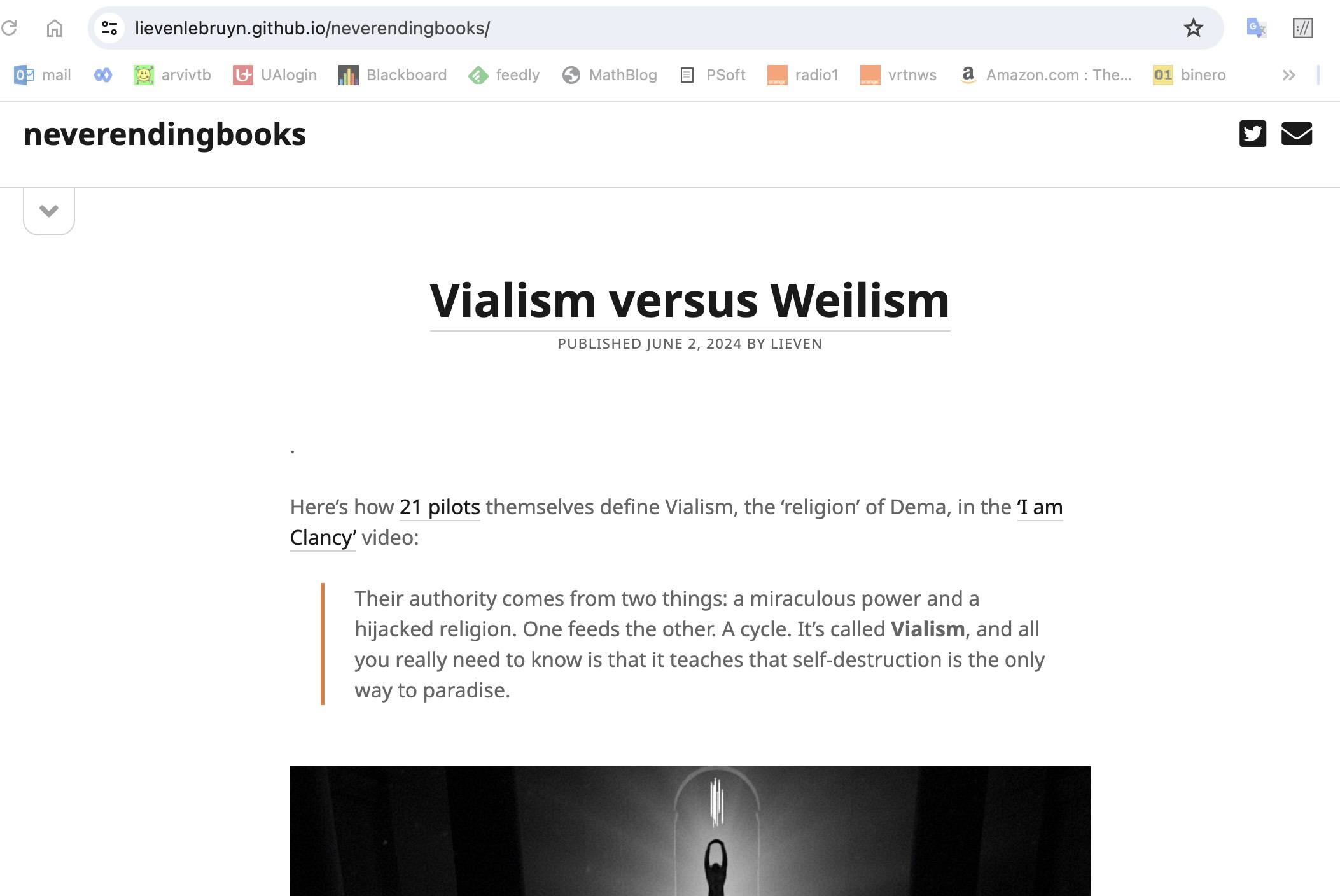

With help from Pieter Belmans I managed to create a static version of this blog on GitHub. Its URL is

https://lievenlebruyn.github.io/neverendingbooks

All internal links should work (if not, please tell me) and if you ever bookmarked a post here with URL something like

http://www.neverendingbooks.org/that_post

you’ll be able to view it till eternity comes using this URL: https://lievenlebruyn.github.io/neverendingbooks/that_post.

The more you link to the static GitHub version from now on, the more likely it is all static NeB posts will show up in a Google search.

I may even continue to blog and will update the GitHub repository whenever I can.

If you ever come in a similar situation (WordPress blogger, whose server will become unavailable, and want to set up a static version of your blog, with the possibility to keep on blogging) I’ll walk you through the main steps (and, if I could do this, anyone can).

1. Install Local.WP

On a computer you will continue to have access to, say your laptop (not serving to the web) install Local.WP which allows you to build local WordPress sites.

2. Clone your blog locally

Set up a default WP-blog, name it as your blog, say myblog, install all plugins you have on your regular blog and set it up to use your preferred theme.

Then. clone your blog with the export/import tool from WP. That is, export your blog and then import it in this local blog and delete the standard first post and page local.WP created.

Oh, and make sure you local site serves https (may be important later if you want to use the GitHub API). The local.wp helpfiles provide you with all info.

3. Get all internal links right

Install the Better search and replace plugin.

Use it to set all your internal links right. Assume your blog has address http://myblog.org and your local version serves it at https://myblog.local do a global search and replace of these two terms.

Check if indeed all local links (including images) work.

4. Make a GitHub repository

Set up a GitHub account, let’s call is myname and set up your first repository and name it after your blog myblog.

5. Do the Simply Static magic

Install on your local blog the Simply Static wordpress plugin.

In the general settings of Simply Static choose for replacing URLs ‘Absolute URLs’ and for scheme/host choose https://myname.github.io/myblog and force URL replacements.

Choose as your deployment method ‘ZIP archive’ and hit generate. When it finishes download the ZIP file.

6. Upload to GitHub pages

Upload the obtained folder to your GitHub repository and make it into a Github-page (lots of pages tell you how you can do both). You’re done, your static site is now available at https://myname.github.io/myblog.

If you would opt for the paid version of Simply Static the last step is done automatically (hence the importance of the https scheme on your local clone) and it promises to make even comments to your static site available as well as semi-automatic updates if you write a new post on your local blog.

Leave a Comment