Until now, we’ve looked at actions of groups (such as the $T/I$ or $PLR$-group) or (transformation) monoids (such as Noll’s monoid) on special sets of musical elements, in particular the twelve pitch classes $\mathbb{Z}_{12}$, or the set of all $24$ major and minor chords.

Elephant-lovers recognise such settings as objects in the presheaf topos on the one-object category $\mathbf{M}$ corresponding to the group or monoid. That is, we look at contravariant functors $\mathbf{M} \rightarrow \mathbf{Sets}$.

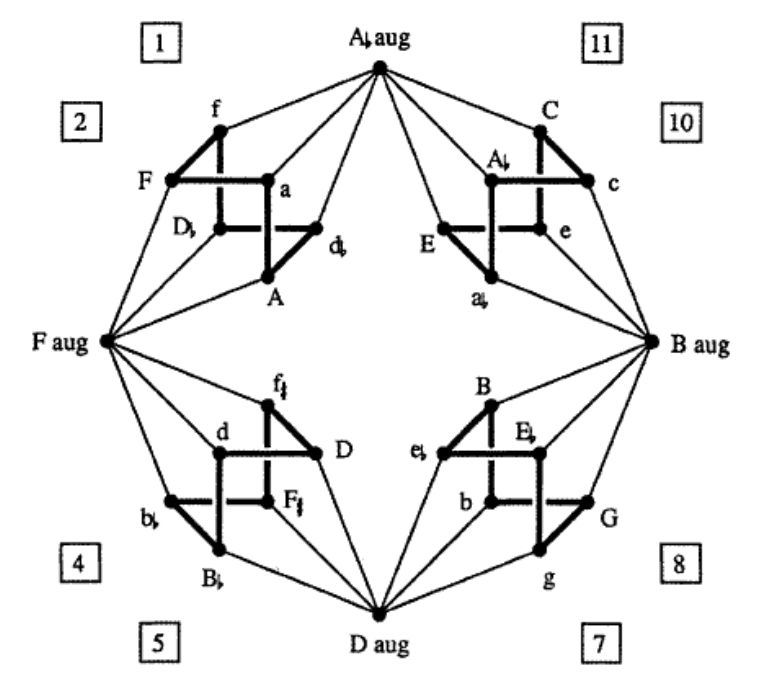

Last time we’ve encountered the ‘Cube Dance Grap’ which depicts a particular relation among the major, minor, and augmented chords.

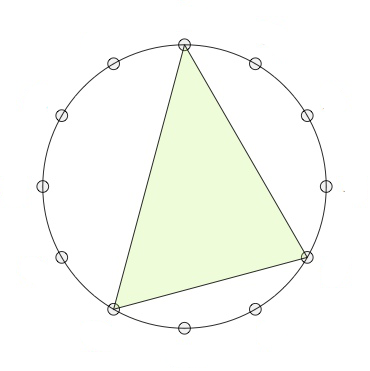

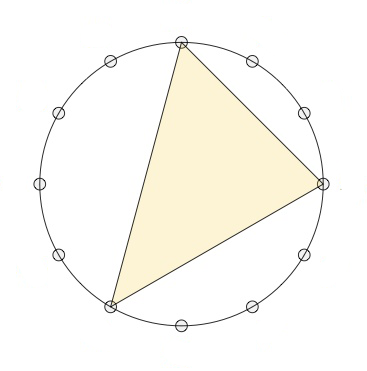

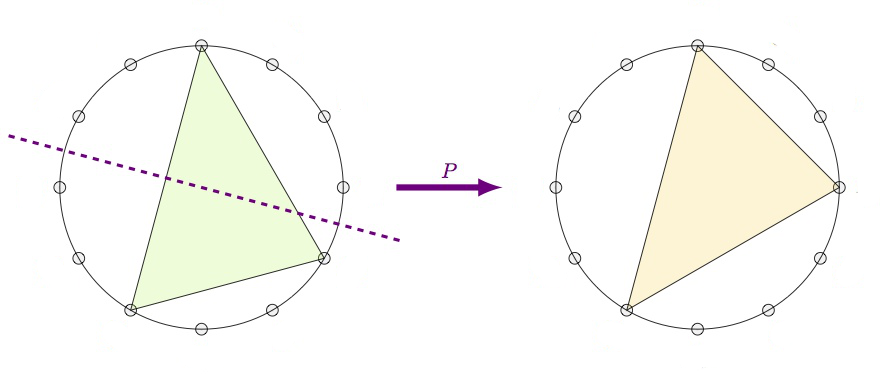

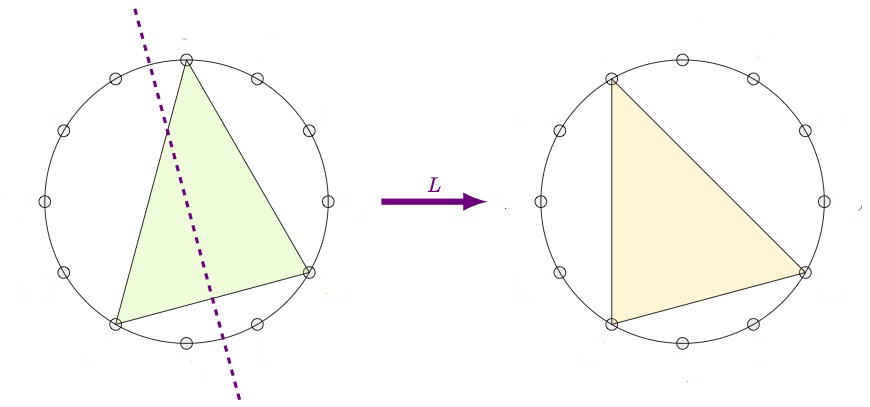

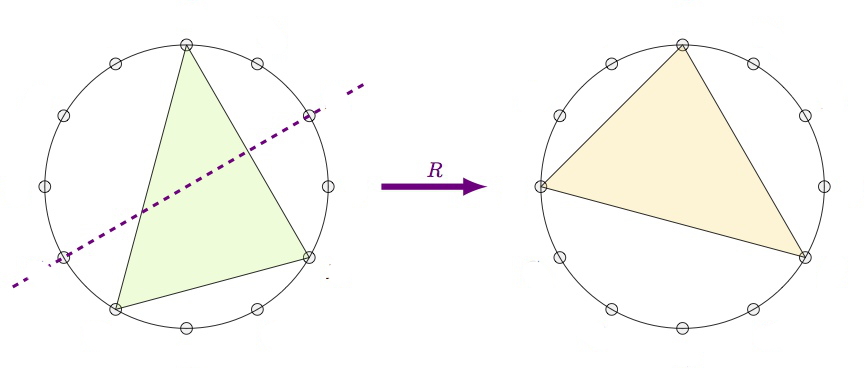

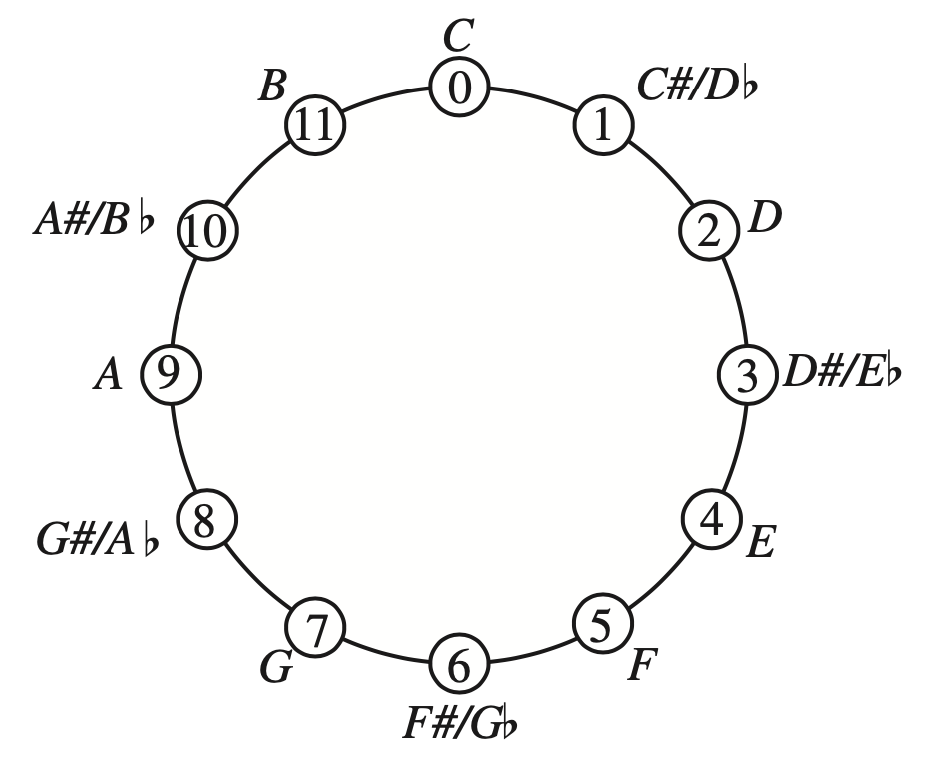

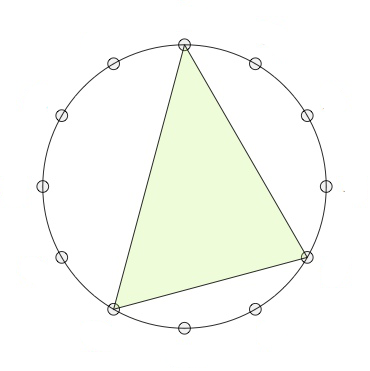

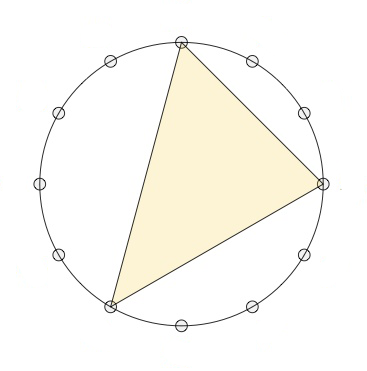

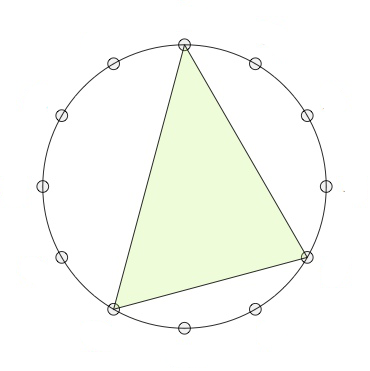

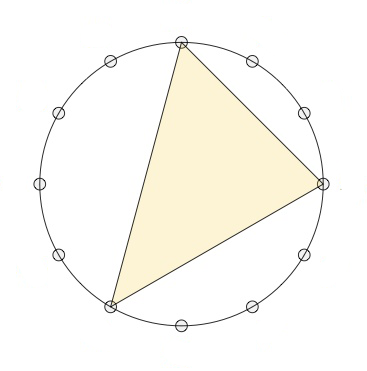

Recall that the twelve major chords (numbered for $1$ to $12$) are the ordered triples of tones in $\mathbb{Z}_{12}$ of the form $(n,n+4,n+7)$ (such as the triangle on the left). The twelve minor chords (numbered from $13$ to $24$) are the ordered triples $(n,n+3,n+7)$ (such as the middle triangle). The four augmented chords (numbered from $25$ to $28$) are the triples of the form $(n,n+4,n+8)$ (such as the rightmost triangle).

The Cube Dance Graph relates two of these chords when they share two tones (pitch classes) whereas the remaining tones differ by a halftone.

Picture modified from this post.

We can separate this symmetric binary relation into three sub-relations: the extension of the $P$ and $L$-operations on major and minor chords to the augmented ones (these are transformations), and the remaining relation $U$ which connects the major and minor chords to the augmented chords (and which is not a transformation).

Binary relations on the same set can be composed, so we get a monoid $\mathbf{M}$ generated by the three relations $P,L$ and $U$. The action of $\mathbf{M}$ on the $28$ chords no longer gives us an ordinary presheaf (because $U$ is not a transformation), but a relational presheaf as in the paper On the use of relational presheaves in transformational music theory by Alexandre Popoff.

That is, the action defines a contravariant functor $\mathbf{M} \rightarrow \mathbf{Rel}$ where $\mathbf{Rel}$ is the category (actually a $2$-category) of sets, but with binary relations as morphisms (that is, $Hom(X,Y)$ is all subsets of $X \times Y$), and the natural notion of composition of such relations. The $2$-morphism between relations is that of inclusion.

To compute with monoids generated by binary relations in GAP one needs to download, compile and load the package semigroups, and to represent the binary relations as partitioned binary relations as in the paper by Martin and Mazorchuk.

This is a bit more complicated than working with ordinary transformations:

P:=PBR([[-13],[-14],[-15],[-16],[-17],[-18],[-19],[-20],[-21],[-22],[-23],[-24],[-1],[-2],[-3],[-4],[-5],[-6],[-7],[-8],[-9],[-10],[-11],[-12],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28]],[[13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[25],[26],[27],[28]]);

L:=PBR([[-17],[-18],[-19],[-20],[-21],[-22],[-23],[-24],[-13],[-14],[-15],[-16],[-9],[-10],[-11],[-12],[-1],[-2],[-3],[-4],[-5],[-6],[-7],[-8],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28]],[[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[13],[14],[15],[16],[9],[10],[11],[12],[1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[25],[26],[27],[28]]);

U:=PBR([[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-17,-21,-13,-4,-8,-12],[-5,-1,-9,-18,-14,-22],[-2,-6,-10,-15,-23,-19],[-24,-16,-20,-11,-3,-7]],[[26],[27],[28],[25],[26],[27],[28],[25],[26],[27],[28],[25],[25],[26],[27],[28],[25],[26],[27],[28],[25],[26],[27],[28],[17,21,13,4,8,12],[5,1,9,18,14,22],[2,6,10,15,23,19],[24,16,20,11,3,7]]);

But then, GAP quickly tells us that $\mathbf{M}$ is a monoid consisting of $40$ elements.

gap> M:=Semigroup([P,L,U]);

gap> Size(M);

40

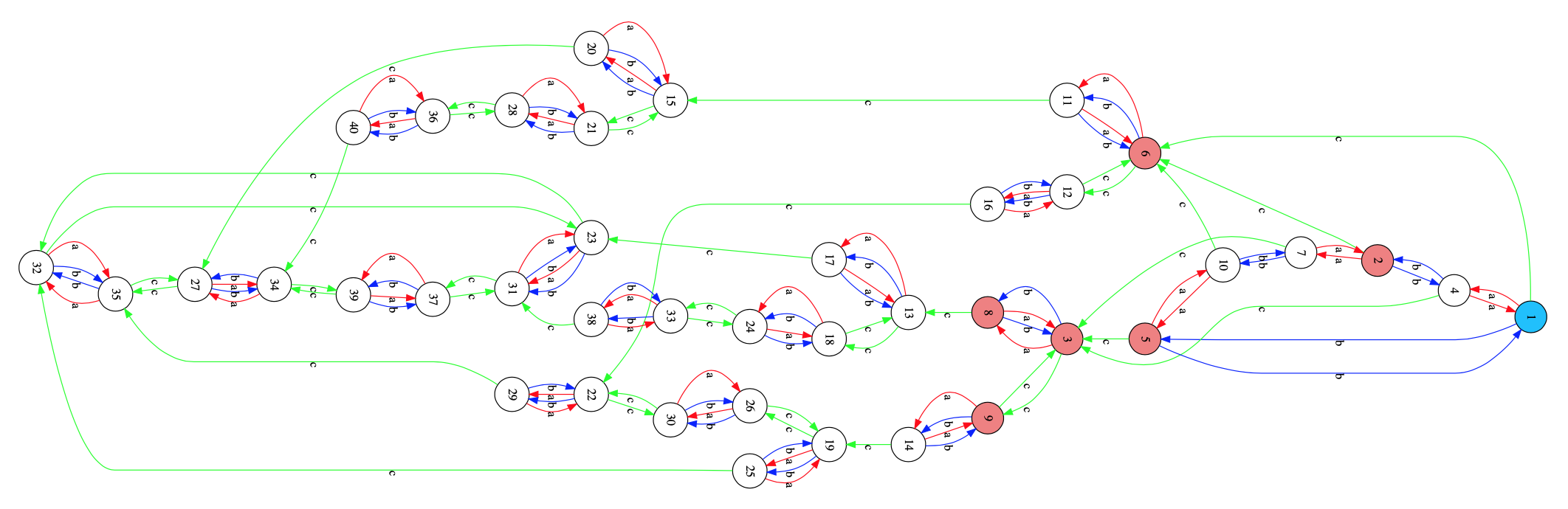

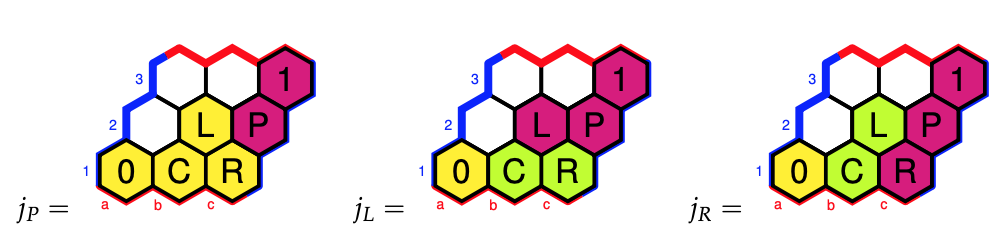

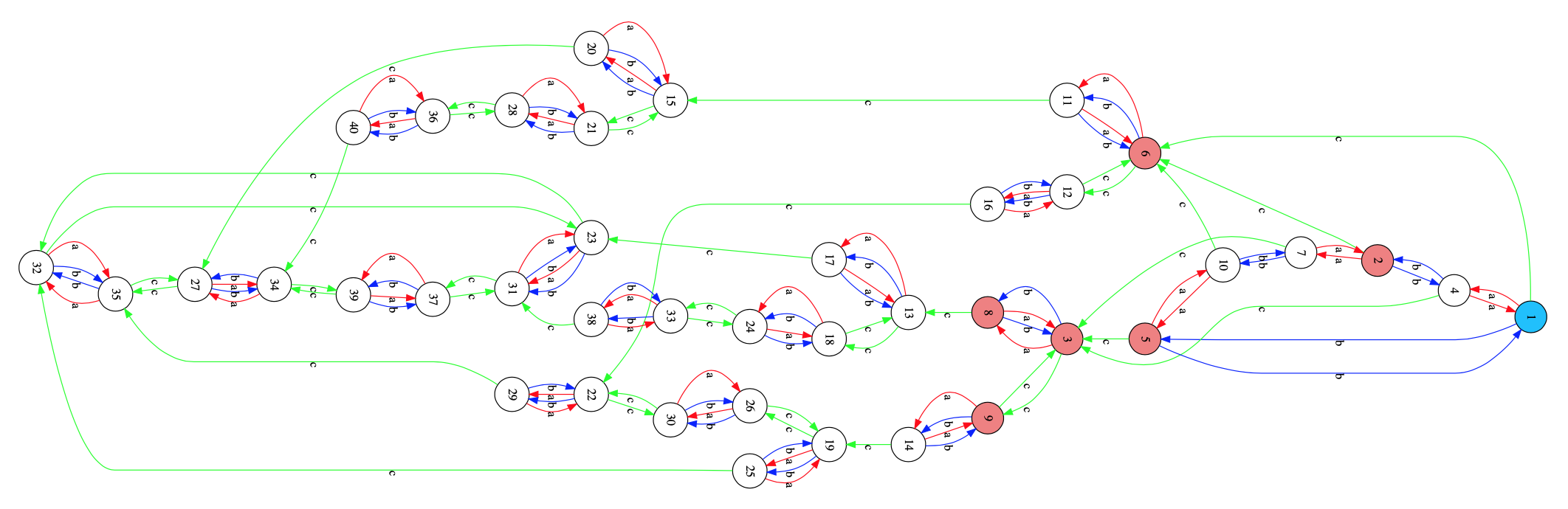

The Semigroups-package can also compute Green’s relations and tells us that there are seven such $R$-classes, four consisting of $6$ elements, two of four, and one of eight elements. These are also visible in the Cayley graph, exactly as last time.

Or, if you prefer the cleaner picture of the Cayley graph from the paper Relational poly-Klumpenhouwer networks for transformational and voice-leading analysis by Popoff, Andreatta and Ehresmann.

This then allows us to compute the Heyting algebra of the subobject classifier, and all the Grothendieck topologies, at least for the ordinary presheaf topos of $\mathbf{M}$-sets, not for the relational presheaves we need here.

We can consider the same binary relation on the larger set of triads when we add the suspended triads. These are the ordered triples in $\mathbb{Z}_{12}$ of the form $(n,n+5,n+7)$, as in the rightmost triangle below.

There are twelve suspended chords (numbered from $29$ to $40$), so we now have a binary relation $T$ on a set of $40$ triads.

The relation $T$ is too coarse, and the art is to subdivide $T$ is disjoint sub-relations which are musically significant, between major and minor triads, between major/minor and augmented triads, and so on.

For each such partition we can then consider the monoids generated by these sub-relations.

In his paper, Popoff suggest relevant sub-relations $P,L,T_U,T_V$ and $T_U \cup T_V$ of $T$ which in our numbering of the $40$ chords can be represented by these PBR’s (assuming I made no mistakes…ADDED march 24th: I did make a mistake in the definition of L, see comment by Alexandre Popoff, below the corect L):

P:=PBR([[-13],[-14],[-15],[-16],[-17],[-18],[-19],[-20],[-21],[-22],[-23],[-24],[-1],[-2],[-3],[-4],[-5],[-6],[-7],[-8],[-9],[-10],[-11],[-12],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-36],[-37],[-38],[-39],[-40],[-29],[-30],[-31],[-32],[-33],[-34],[-35]],[[13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[25],[26],[27],[28],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33]]);

L:=PBR([[-17],[-18],[-19],[-20],[-21],[-22],[-23],[-24],[-13],[-14],[-15],[-16],[-9],[ -10],[-11],[-12],[-1],[-2],[-3],[-4],[-5],[-6],[-7],[-8],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-29], [-30],[-31],[-32],[-33],[-34],[-35],[-36],[-37],[-38],[-39],[-40]],[[17], [18], [19], [ 20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[13],[14],[15],[16],[9],[10],[11],[12],[1],[2],[3],[4],[5], [6], [7],[8],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40] ]);

TU:=PBR([[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-25],[-26],[-27],[-28],[-4,-8,-12,-13,-17,-21],[-1,-5,-9,-14,-18,-22],[-2,-6,-10,-15,-19,-23],[-3,-7,-11,-16,-20,-24],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[]],[[26],[27],[28],[25],[26],[27],[28],[25],[26],[27],[28],[25],[25],[26],[27],[28],[25],[26],[27],[28],[25],[26],[27],[28],[4,8,12,13,17,21],[1,5,9,14,18,22],[2,6,10,15,19,23],[3,7,11,16,20,24],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[],[]]);

TV:=PBR([[-29],[-30],[-31],[-32],[-33],[-34],[-35],[-36],[-37],[-38],[-39],[-40],[-36],[-37],[-38],[-39],[-40],[-29],[-30],[-31],[-32],[-33],[-34],[-35],[],[],[],[],[-1,-18],[-2,-19],[-3,-20],[-4,-21],[-5,-22],[-6,-23],[-7,-24],[-8,-13],[-9,-14],[-10,-15],[-11,-16],[-12,-17]],[[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[],[],[],[],[1,18],[2,19],[3,20],[4,21],[5,22],[6,23],[7,24],[8,13],[9,14],[10,15],[11,16],[12,17]]);

TUV:=PBR([[-26,-29],[-27,-30],[-28,-31],[-25,-32],[-26,-33],[-27,-34],[-28,-35],[-25,-36],[-26,-37],[-27,-38],[-28,-39],[-25,-40],[-25,-36],[-26,-37],[-27,-38],[-28,-39],[-25,-40],[-26,-29],[-27,-30],[-28,-31],[-25,-32],[-26,-33],[-27,-34],[-28,-35],[-4,-8,-12,-13,-17,-21],[-1,-5,-9,-14,-18,-22],[-2,-6,-10,-15,-19,-23],[-3,-7,-11,-16,-20,-24],[-1,-18],[-2,-19],[-3,-20],[-4,-21],[-5,-22],[-6,-23],[-7,-24],[-8,-13],[-9,-14],[-10,-15],[-11,-16],[-12,-17]],[[26,29],[27,30],[28,31],[25,32],[26,33],[27,34],[28,35],[25,36],[26,37],[27,38],[28,39],[25,40],[25,36],[26,37],[27,38],[28,39],[25,40],[26,29],[27,30],[28,31],[25,32],[26,33],[27,34],[28,35],[4,8,12,13,17,21],[1,5,9,14,18,22],[2,6,10,15,19,23],[3,7,11,16,20,24],[1,18],[2,19],[3,20],[4,21],[5,22],[6,23],[7,24],[8,13],[9,14],[10,15],[11,16],[12,17]]);

The resulting monoids are huge:

gap> G:=Semigroup([P,L,TU,TV]);

gap> Size(G);

473293

gap> H:=Semigroup([P,L,TUV]);

gap> Size(H);

994624

In Popoff’s paper these monoids have sizes respectively $473,293$ and $994,624$. Strangely, the offset is in both cases $144=12^2$. (Added march 24: with the correct L I get the same sizes as in Popoff’s paper).

Perhaps we should try to transform such relational presheaves to ordinary presheaves.

One approach is to use the Grothendieck construction and associate to a set with such a relational monoid action a directed graph, coloured by the elements of the monoid. That is, an object in the presheaf topos of the category

\[

\xymatrix{C & E \ar[l]^c \ar@/^2ex/[r]^s \ar@/_2ex/[r]_t & V} \]

and then we should consider the slice topos over the one-vertex bouquet graph with one loop for each element in the monoid.

If you want to have more details on the musical side of things, for example if you want to know what the opening twelve chords of “Take a Bow” by Muse have to do with the Cube Dance graph, here are some more papers:

A categorical generalization of Klumpenhouwer networks, A. Popoff, M. Andreatta and A. Ehresmann.

From K-nets to PK-nets: a categorical approach, A. Popoff, M. Andreatta and A. Ehresmann.

From a Categorical Point of View: K-Nets as Limit Denotators, G. Mazzola and M. Andreatta.