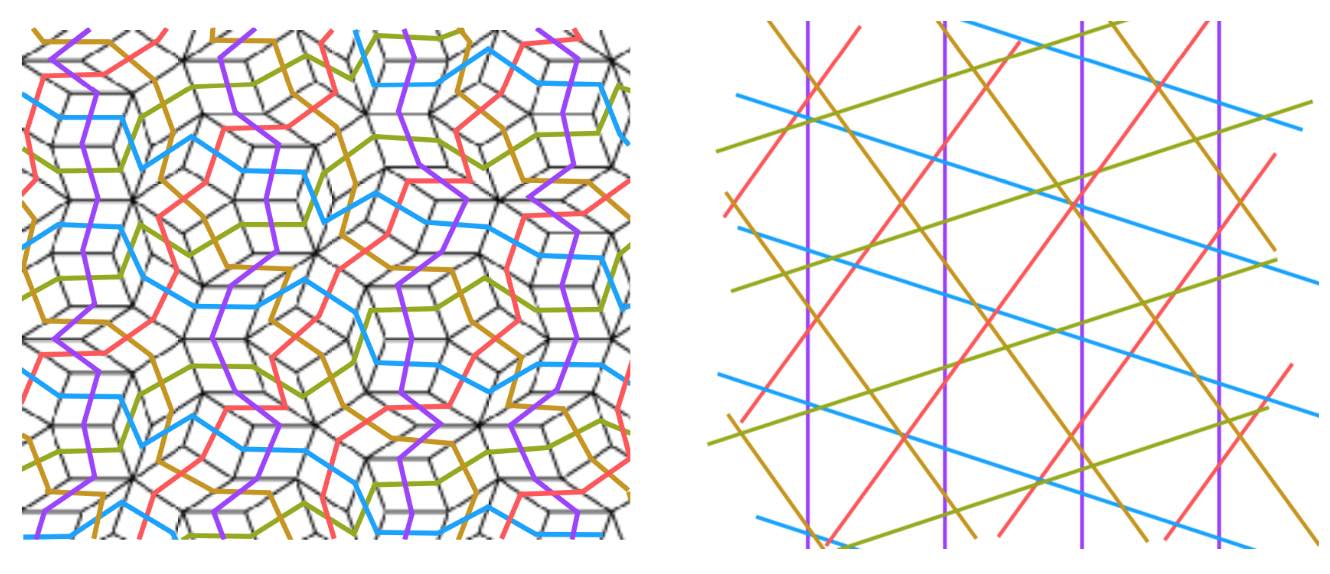

In a Rhombic tiling (aka a Penrose P3 tiling) we can identify five ribbons.

Opposite sides of a rhomb are parallel. We may form a ribbon by attaching rhombs along opposite sides. There are five directions taken by sides, so there are five families of ribbons that do not intersect, determined by the side directions.

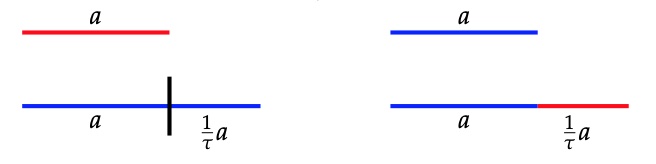

Every ribbon determines a skeleton curve through the midpoints of opposite sides of the rhombs. If we straighten these skeleton curves we get a de Bruijn’s pentagrid.

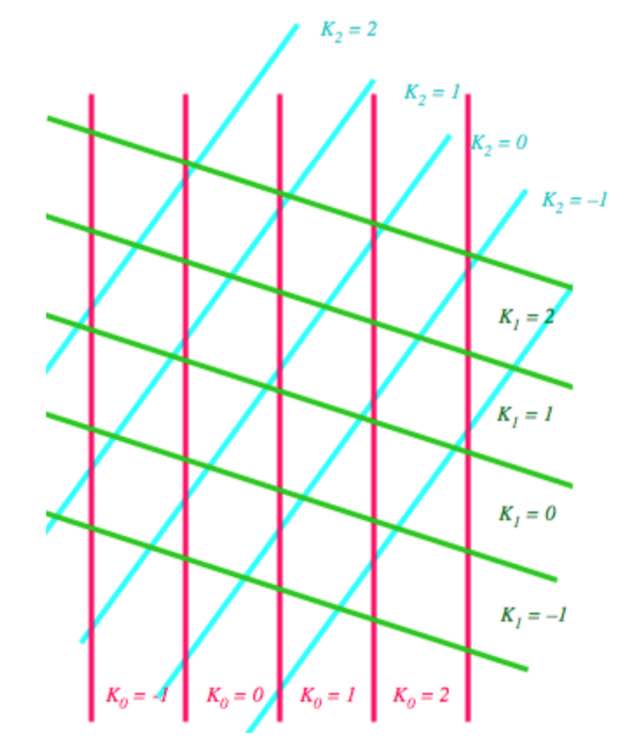

A pentagrid is a grid of the plane consisting of five families of parallel lines, at angles multiples of $72^o = 360^o/5$, and with each family consisting of parallel lines with a spacing given by a number $\gamma_i$ for $0 \leq i \leq 4$, satisfying

\[

\gamma_0+\gamma_1+\gamma_2+\gamma_3+\gamma_4=0 \]

The points of the plane in the $j$-th family of the pentagrid are

\[

\{ \vec{x} \in \mathbb{R}^2~|~\vec{x}.\vec{v}_j + \gamma_j \in \mathbb{Z} \} \]

where $\vec{v}_j = \zeta^j = (cos(2 \pi j/5),sin(2 \pi j/5))$.

A pentagrid is regular if no point in $\mathbb{R}^2$ belongs to more than two of the five grids. For almost all choices $\gamma_0,\dots,\gamma_4$ the corresponding pentagrid is regular. The pentagrid coordinates of a point $\vec{x} \in \mathbb{R}^2$ are the five integers $(K_0(\vec{x}),\dots,K_4(\vec{x}) \in \mathbb{Z}^5$ defined by

\[

K_j(\vec{x}) = \lceil \vec{x}.\vec{v}_j + \gamma_j \rceil \]

with $\lceil r \rceil$ the smallest integer greater of equal to $r$, and clearly the function $K_j(\vec{x})$ is constant in regions between the $j$-th grid lines.

With these pentagrid-coordinates one can associate a vertex to any point $\vec{x} \in \mathbb{R}^2$

\[

V(\vec{x}) = \sum_{j=0}^4 K_j(\vec{x}) \vec{v}_j \]

which is constant in regions between grid lines.

Here’s de Bruijn‘s result:

For $\vec{x}$ running over $\mathbb{R}^2$, the vertices $V(\vec{x})$ coming from a pentagrid determine a Rhombic tiling of the plane. Even better, every Rhombic tiling comes from a pentagrid.

We’ll prove this for regular pentagrids (the singular case follows from a small deformation).

Any intersection point $\vec{x}_0$ of the pentagrid belongs to exactly two families of parallel lines, so we have two integers $r$ and $s$ with $0 \leq r < s \leq 4$ and integers $k_r,k_s \in \mathbb{Z}$ such that $\vec{x}_0$ is determined by the equations \[ \begin{cases} \vec{x}.\vec{v}_r + \gamma_r = k_r \\ \vec{x}.\vec{v}_s + \gamma_s = k_s \end{cases} \] In a small neighborhood of $\vec{x}_0$, $V(\vec{x})$ takes the values of four vertices of a rhomb. These vertices are associated to the $5$-tuples in $\mathbb{Z}^5$ given by \[ (K_0(\vec{x}_0),\dots,K_4(\vec{x}_0))+\epsilon_1 (\delta_{0r},\dots,\delta_{4r})+\epsilon_2 (\delta_{0s},\dots,\delta_{4s}) \] with $\epsilon_1,\epsilon_2 \in \{ 0,1 \}$. So, the intersection points of the regular pentagrid lines correspond to rhombs, and the regions between the grid lines (which are called meshes) correspond to vertices, whose positions are given by $V(\vec{x})$.

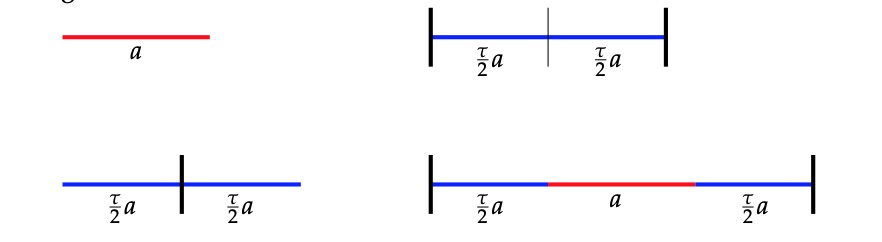

Observe that these four vertices give a thin rhombus if the angle between $\vec{v}_r$ and $\vec{v}_s$ is $144^o$ and determine a thick rhombus if the angle is $72^o$.

Not all pentagrid coordinates $(k_0,\dots,k_4)$ occur in the tiling though. For $\vec{x} \in \mathbb{R}^2$ we have

\[

K_j(\vec{x}) = \vec{x}.\vec{v}_j + \gamma_j + \lambda_j(\vec{x}) \]

with $0 \leq \lambda_j(\vec{x}) < 1$. In a regular pentagrid at most two of the $\lambda_j(\vec{x})$ can be zero and so we have

\[

0 < \lambda_0(\vec{x}) + \dots + \lambda_4(\vec{x}) < 5 \]

and we have assumed that $\gamma_0 + \dots + \gamma_4 = 0$, giving us

\[

\sum_{j=0}^4 K_j(\vec{x}) = \vec{x}.(\sum_{j=0}^4 \vec{v}_j) + \sum_{j=0}^4 \gamma_j + \sum_{j=0}^4 \lambda_j(\vec{x}) = \sum_{j=0}^4 \lambda_j(\vec{x}) \]

The left hand side must be an integers and the right hand side a number strictly between $0$ and $5$. This defines the index of a vertex

\[

ind(\vec{x}) = \sum_{j=0}^4 K_j(\vec{x}) \in \{ 1,2,3,4 \} \]

Therefore, every vertex in the tiling may be represented as

\[

k_0 \vec{v}_0 + \dots + k_4 \vec{v}_4 \]

with $(k_0,\dots,k_4) \in \mathbb{Z}^5$ satisfying $\sum_{j=0}^4 k_j \in \{ 1,2,3,4 \}$. If we move a point along the edges of a rhombus, we note that the index increases by $1$ in the directions of $\vec{v}_0,\dots,\vec{v}_4$ and decreases by $1$ in the directions $-\vec{v}_0,\dots,-\vec{v}_4$.

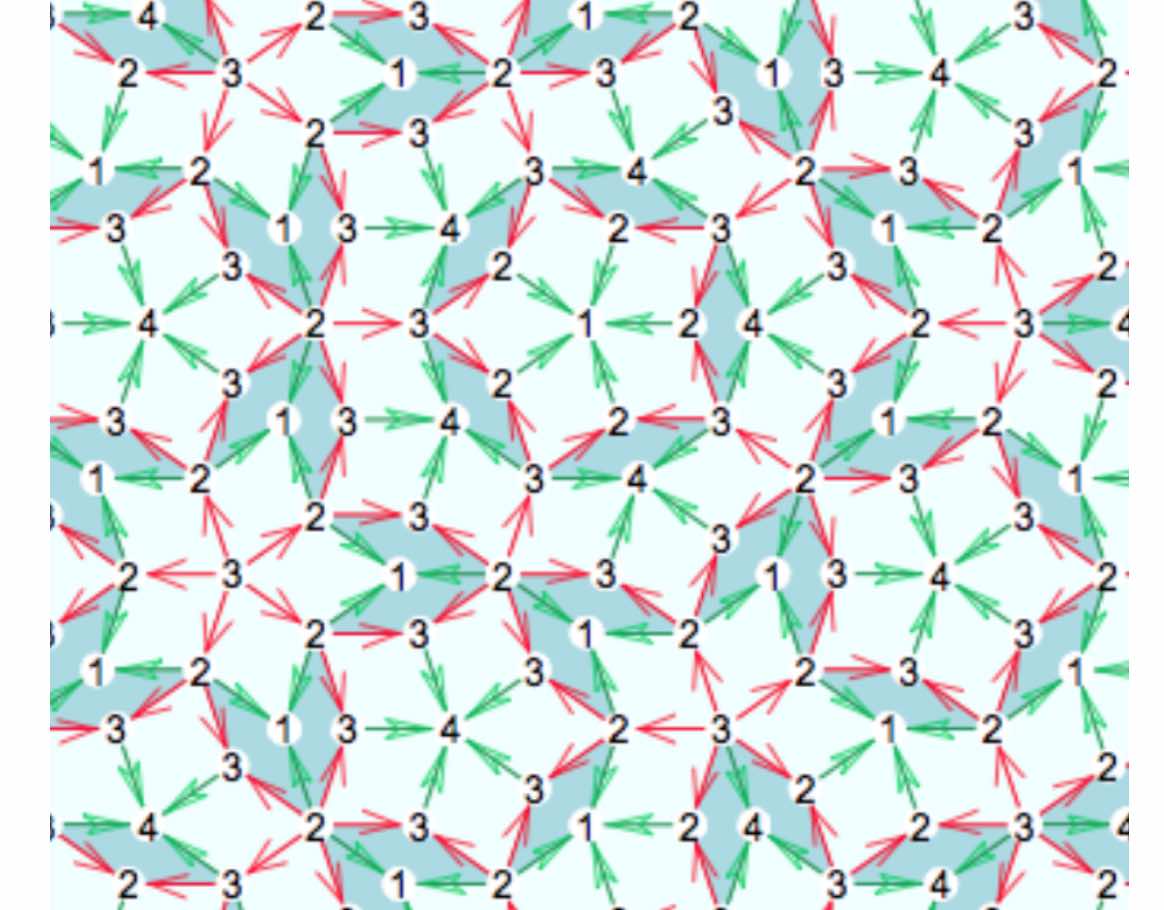

It follows that the index-values of the vertices of a thick rhombus are either $1$ and $3$ at the $72^o$ angles and $2$ at the $108^o$ angles, or they are $2$ and $4$ at the $72^o$ angles, and $3$ at the $108^o$ angles. For a thin rhombus the index-values must be either $1$ and $3$ at the $144^o$ angles and $2$ at the $36^o$ angles, or $2$ and $4$ at the $144^o$ angles and $3$ at the $36^o$ angles.

We still have to show that this gives a legal Rhombic tiling, that is, that the gluing restrictions of Penrose’s rhombs are satisfied.

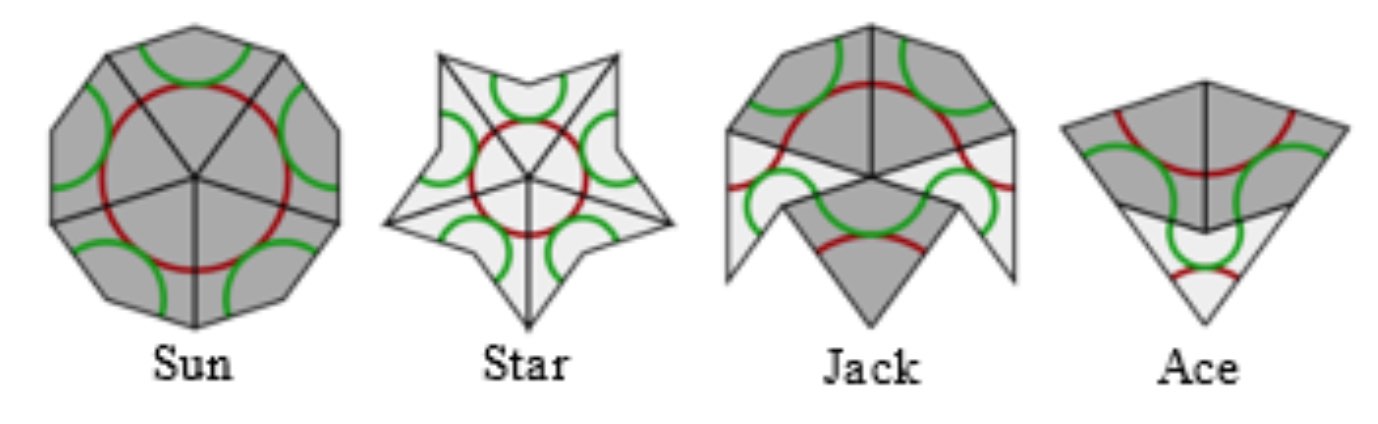

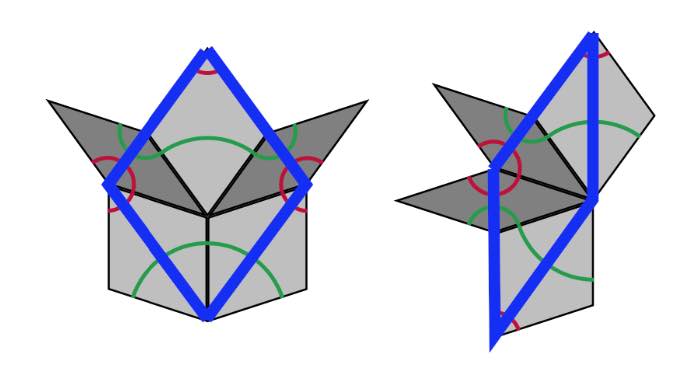

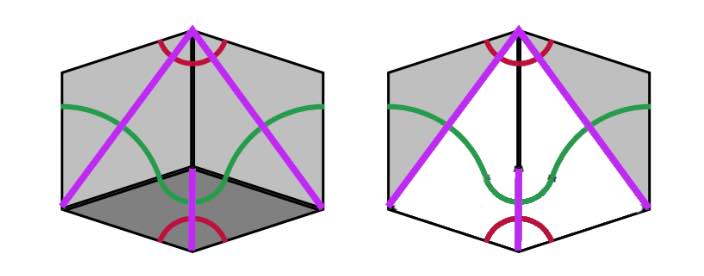

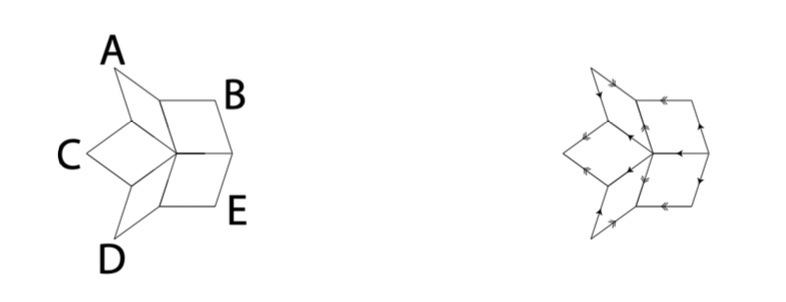

We do this by orienting and colouring the edges of the thin and thick rhombus towards the vertex defined by the semi-circles on the rhombus-pieces. Edges connecting a point of index $3$ to a point of index $2$ are coloured red, edges connecting a point of index $1$ to a point of index $2$, or connecting a point of index $3$ to one of index $4$ are coloured blue.

We orient green edges pointing from index $2$ to index $1$, or from index $3$ to index $4$. As this orientation depends only on the index-values of the vertices, two rhombs sharing a common green edge also have the same orientation on that edge.

On each individual rhomb, knowing the green edges and their orientation forced the red edges and their orientation, but we still have to show that if two rhombs share a common red edge, this edge has the same orientation on both (note in the picture above that a red edge can both flow from $2$ to $3$ as well as from $3$ to $2$).

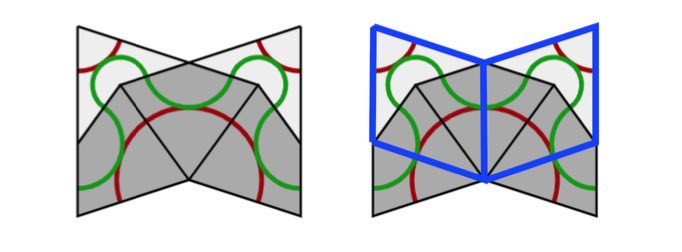

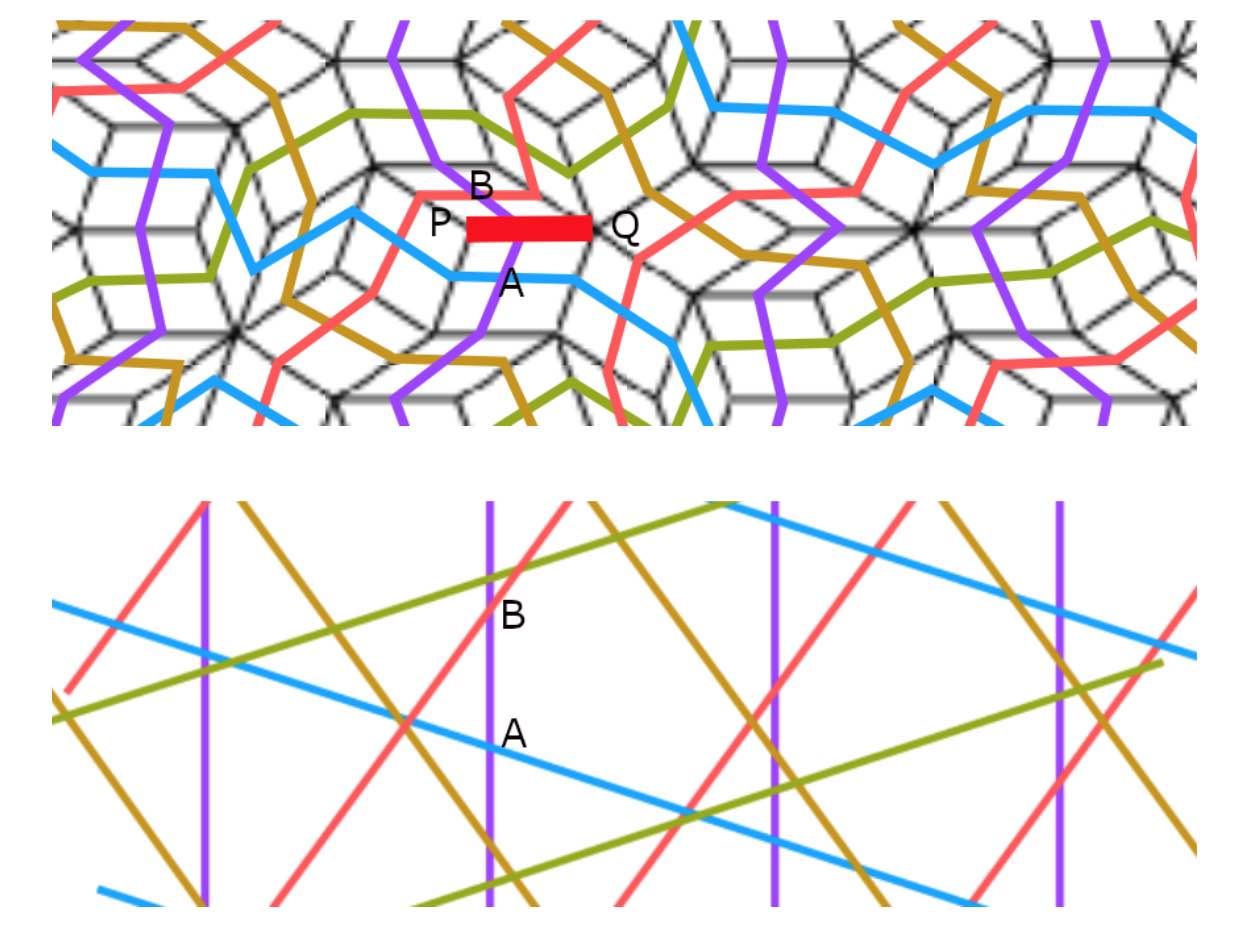

From the gluing conditions of Penrose’s rhombs we see that if $PQ$ be a red edge, in common to two rhombs, and these rhombs have angle $\alpha$ resp. $\beta$ in $P$, then $\alpha$ and $\beta$ must be both less that $90^o$ or both bigger than $90^o$. We translate this in terms of the pentragrid.

The two rhombs correspond to two intersection points $A$ and $B$, and we may assume that they both lie on a line $l$ of family $0$ of parallel lines (other cases are treated similarly by cyclic permutation), and that $A$ is an intersection with a family $p$-line and $B$ with a family $q$-line, with $p,q \in \{ 1,2,3,4 \}$. The interval $AB$ crosses the unique edge common to the two rhombs determined by $A$ and $B$, and we call the interval $AB$ red if $\sum_j K_j(\vec{x})$ is $2$ on one side of $AB$ and $3$ on the other side. The claim about the angles $\alpha$ and $\beta$ above now translates to: if $AB$ is red, then $p+q$ is odd (in the picture above $p=1$ and $q=2$).

By a transformation we may assume that $\gamma_0=0$ and that $l$ is the $Y$-axis. For every $y \in \mathbb{R}$ we then get

\[

\begin{cases}

K_1(0,y) = \lceil y .sin(2 \pi/5) + \gamma_1 \rceil \\

K_2(0,y) = \lceil y .sin(4 \pi/5) + \gamma_2 \rceil \\

K_3(0,y) = \lceil -y .sin(4 \pi/5) + \gamma_3 \rceil \\

K_4(0,y) = \lceil -y .sin(2 \pi/5) + \gamma_4 \rceil

\end{cases}

\]

and $\gamma_1+\gamma_4$ and $\gamma_2+\gamma_3$ are not integers (otherwise the pentagrid is not regular). If $y$ runs from $-\infty$ to $+\infty$ we find that

\[

K_1(0,y)+K_4(0,y) – \lceil \gamma_1 + \gamma_4 \rceil = \begin{cases} 0 \\ 1 \end{cases} \]

with jumps from $0$ to $1$ at places where $(\lceil \gamma_1 + \gamma_4 \rceil – \gamma_1)/sin(2 \pi/5) \in \mathbb{Z}$ and from $1$ to $0$ when $\gamma_4/sin(2 \pi/5) \in \mathbb{Z}$. (A similar result holds replacing $K_1,K_4,\gamma_1,\gamma_4,sin(2 \pi/5)$ by $K_2,K_3,\gamma_2,\gamma_3,sin(4 \pi/5)$.

Because the points on $l$ intersecting with $1$-family and $4$-family gridlines alternate (and similarly for $2$- and $3$-family gridlines) we know already that $p \not= q$. If we assume that $p+q$ is even, we have two possibilities, either $\{p,g \}=\{ 1,3 \}$ or $\{ 2,4 \}$. As $\gamma_0=0$ we have $\gamma_1+\gamma_2+\gamma_3+\gamma_4=0$ and therefore

\[

\lceil \gamma_1 + \gamma_4 \rceil + \lceil \gamma_2+\gamma_3 \rceil = 1 \]

It then follows that $K_1(0,y)+K_2(0,y)+K_3(0,y)+K_4(0,y) = 1$ or $3$ between the points $A$ and $B$. Therefore $K_0(y,0) + \dots + K_4(0,y)$ is either $1$ on the left side and $2$ on the right side, or is $3$ on the left side and $4$ on the right side, so $AB$ must be green, a contradiction. Therefore, $p+q$ is odd, and the orientation of the red edge in both rhombs is the same. Done!

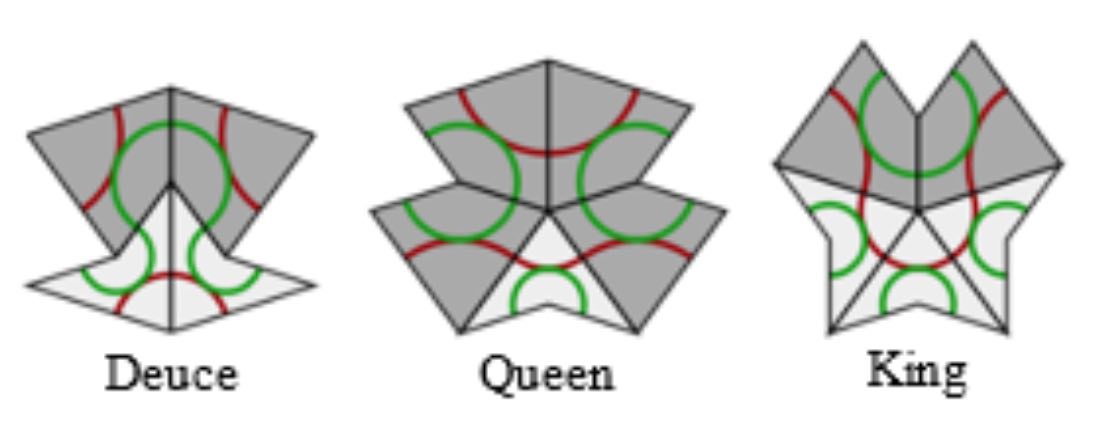

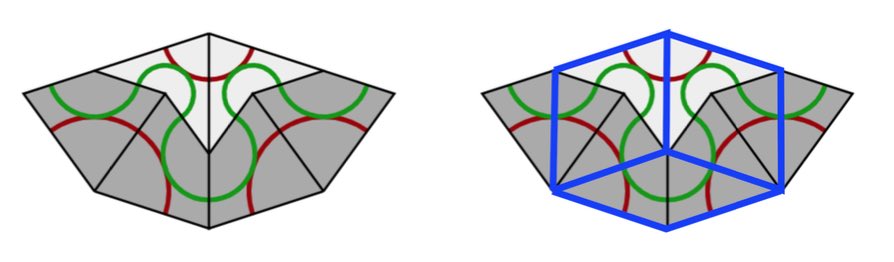

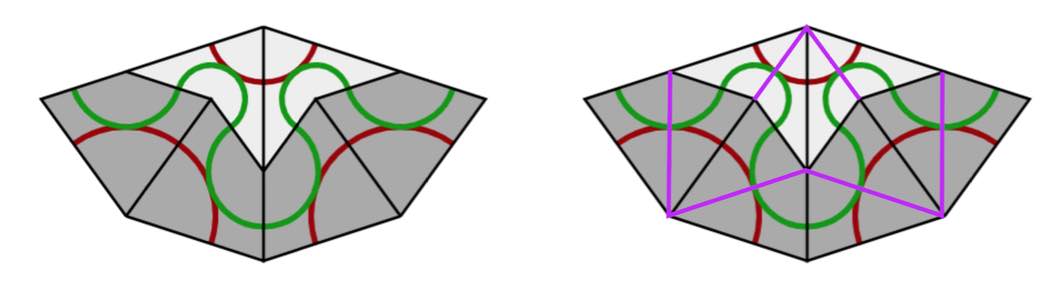

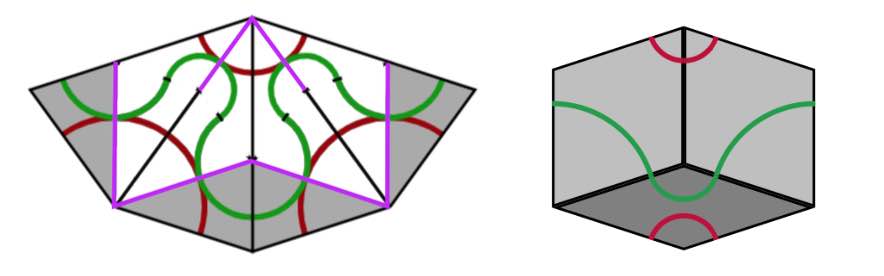

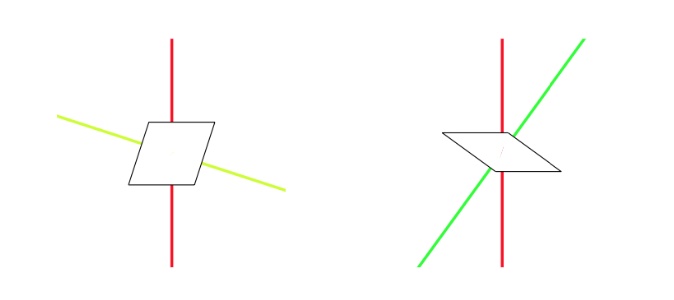

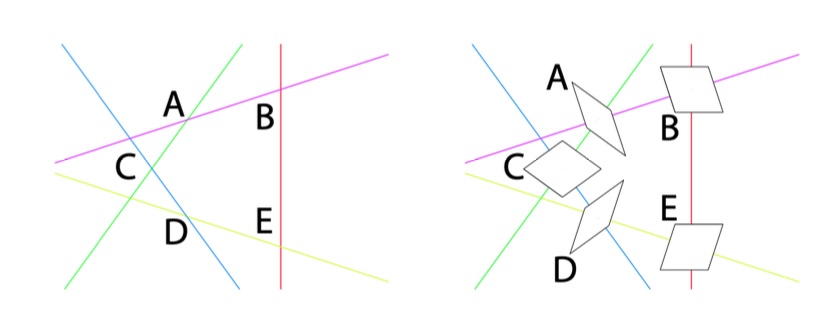

An alternative way to see this correspondence between regular pentagrids and Rhombic tilings as as follows. To every intersection of two gridlines we assign a rhombus, a thin one if they meet at an acute angle of $36^o$ and a thich one if this angle is $72^o$, with the long diagonal dissecting the obtuse angle.

Do this for all intersections, surrounding a given mesh.

Attach the rhombs by translating them towards the mesh, and finally draw the colours of the edges.

Another time, we will connect this to the cut-and-project method, using the representation theory of $D_5$.

One Comment