It’s been a while, so let’s include a recap : a (transitive) permutation representation of the modular group $\Gamma = PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ is determined by the conjugacy class of a cofinite subgroup $\Lambda \subset \Gamma $, or equivalently, to a dessin d’enfant. We have introduced a quiver (aka an oriented graph) which comes from a triangulation of the compactification of $\mathbb{H} / \Lambda $ where $\mathbb{H} $ is the hyperbolic upper half-plane. This quiver is independent of the chosen embedding of the dessin in the Dedeking tessellation. (For more on these terms and constructions, please consult the series Modular subgroups and Dessins d’enfants).

Why are quivers useful? To start, any quiver $Q $ defines a noncommutative algebra, the path algebra $\mathbb{C} Q $, which has as a $\mathbb{C} $-basis all oriented paths in the quiver and multiplication is induced by concatenation of paths (when possible, or zero otherwise). Usually, it is quite hard to make actual computations in noncommutative algebras, but in the case of path algebras you can just see what happens.

Moreover, we can also see the finite dimensional representations of this algebra $\mathbb{C} Q $. Up to isomorphism they are all of the following form : at each vertex $v_i $ of the quiver one places a finite dimensional vectorspace $\mathbb{C}^{d_i} $ and any arrow in the quiver

[tex]\xymatrix{\vtx{v_i} \ar[r]^a & \vtx{v_j}}[/tex] determines a linear map between these vertex spaces, that is, to $a $ corresponds a matrix in $M_{d_j \times d_i}(\mathbb{C}) $. These matrices determine how the paths of length one act on the representation, longer paths act via multiplcation of matrices along the oriented path.

A necklace in the quiver is a closed oriented path in the quiver up to cyclic permutation of the arrows making up the cycle. That is, we are free to choose the start (and end) point of the cycle. For example, in the one-cycle quiver

[tex]\xymatrix{\vtx{} \ar[rr]^a & & \vtx{} \ar[ld]^b \\ & \vtx{} \ar[lu]^c &}[/tex]

the basic necklace can be represented as $abc $ or $bca $ or $cab $. How does a necklace act on a representation? Well, the matrix-multiplication of the matrices corresponding to the arrows gives a square matrix in each of the vertices in the cycle. Though the dimensions of this matrix may vary from vertex to vertex, what does not change (and hence is a property of the necklace rather than of the particular choice of cycle) is the trace of this matrix. That is, necklaces give complex-valued functions on representations of $\mathbb{C} Q $ and by a result of Artin and Procesi there are enough of them to distinguish isoclasses of (semi)simple representations! That is, linear combinations a necklaces (aka super-potentials) can be viewed, after taking traces, as complex-valued functions on all representations (similar to character-functions).

In physics, one views these functions as potentials and it then interested in the points (representations) where this function is extremal (minimal) : the vacua. Clearly, this does not make much sense in the complex-case but is relevant when we look at the real-case (where we look at skew-Hermitian matrices rather than all matrices). A motivating example (the Yang-Mills potential) is given in Example 2.3.2 of Victor Ginzburg’s paper Calabi-Yau algebras.

Let $\Phi $ be a super-potential (again, a linear combination of necklaces) then our commutative intuition tells us that extrema correspond to zeroes of all partial differentials $\frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial a} $ where $a $ runs over all coordinates (in our case, the arrows of the quiver). One can make sense of differentials of necklaces (and super-potentials) as follows : the partial differential with respect to an arrow $a $ occurring in a term of $\Phi $ is defined to be the path in the quiver one obtains by removing all 1-occurrences of $a $ in the necklaces (defining $\Phi $) and rearranging terms to get a maximal broken necklace (using the cyclic property of necklaces). An example, for the cyclic quiver above let us take as super-potential $abcabc $ (2 cyclic turns), then for example

$\frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial b} = cabca+cabca = 2 cabca $

(the first term corresponds to the first occurrence of $b $, the second to the second). Okay, but then the vacua-representations will be the representations of the quotient-algebra (which I like to call the vacualgebra)

$\mathcal{U}(Q,\Phi) = \frac{\mathbb{C} Q}{(\partial \Phi/\partial a, \forall a)} $

which in ‘physical relevant settings’ (whatever that means…) turn out to be Calabi-Yau algebras.

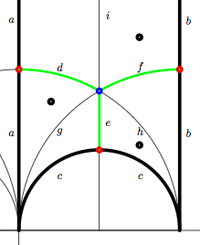

But, let us return to the case of subgroups of the modular group and their quivers. Do we have a natural super-potential in this case? Well yes, the quiver encoded a triangulation of the compactification of $\mathbb{H}/\Lambda $ and if we choose an orientation it turns out that all ‘black’ triangles (with respect to the Dedekind tessellation) have their arrow-sides defining a necklace, whereas for the ‘white’ triangles the reverse orientation makes the arrow-sides into a necklace. Hence, it makes sense to look at the cubic superpotential $\Phi $ being the sum over all triangle-sides-necklaces with a +1-coefficient for the black triangles and a -1-coefficient for the white ones. Let’s consider an index three example from a previous post

[tex]\xymatrix{& & \rho \ar[lld]_d \ar[ld]^f \ar[rd]^e & \\

i \ar[rrd]_a & i+1 \ar[rd]^b & & \omega \ar[ld]^c \\

& & 0 \ar[uu]^h \ar@/^/[uu]^g \ar@/_/[uu]_i &}[/tex]

In this case the super-potential coming from the triangulation is

$\Phi = -aid+agd-cge+che-bhf+bif $

and therefore we have a noncommutative algebra $\mathcal{U}(Q,\Phi) $ associated to this index 3 subgroup. Contrary to what I believed at the start of this series, the algebras one obtains in this way from dessins d’enfants are far from being Calabi-Yau (in whatever definition). For example, using a GAP-program written by Raf Bocklandt Ive checked that the growth rate of the above algebra is similar to that of $\mathbb{C}[x] $, so in this case $\mathcal{U}(Q,\Phi) $ can be viewed as a noncommutative curve (with singularities).

However, this is not the case for all such algebras. For example, the vacualgebra associated to the second index three subgroup (whose fundamental domain and quiver were depicted at the end of this post) has growth rate similar to that of $\mathbb{C} \langle x,y \rangle $…

I have an outlandish conjecture about the growth-behavior of all algebras $\mathcal{U}(Q,\Phi) $ coming from dessins d’enfants : the algebra sees what the monodromy representation of the dessin sees of the modular group (or of the third braid group).

I can make this more precise, but perhaps it is wiser to calculate one or two further examples…