Since wednesday, as mentioned last time, the book by Alain Connes and Patrick Gauthier-Lafaye: “A l’ombre de Grothendieck et de Lacan, un topos sur l’inconscient” is available in the better bookshops.

There’s no need to introduce Alain Connes on this blog. Patrick Gauthier-Lafaye is a French psychiatrist and psycho-analyst, working in Strassbourg.

The book is a lengthy dialogue in which the authors try to find a use for topos theory in Jaques Lacan’s psycho-analytical view of the unconscious.

If you are a complete Lacanian virgin, it may be helpful to browse through “Lacan, a beginners guide” (by Lionel Bailly) first.

If this left you bewildered, for example by Lacan’s strange (ab)use of mathematics, rest assured, you’re not alone.

It is no coincidence that Lacan’s works are the first case-study in the book “Fashionable Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals’ Abuse of Science” by Alan Sokal (the one of the hoax) and Jean Bricmont. You can download the book from this link.

If now you feel that Sokal and Bricmont are way too harsh on Lacan, I urge you to have a go at the book “Writing the structures of the subject, Lacan and topology” by Will Greenshields.

If you don’t have the time or energy for this, let me give you one illustrative example: the topological explanation of Lacan’s formula of fantasy:

\[

\$~\diamond~a \]

Loosely speaking this formula says “the barred subject stands within a circular relationship to the objet petit a (the object of desire), one part of which is determined by alienation, the other by separation”.

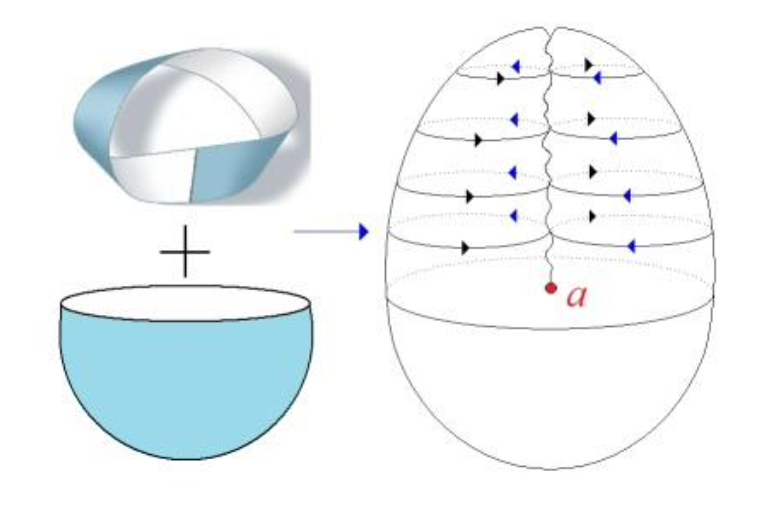

Lacan was obsessed with the immersion of the projective plane $\mathbb{P}^2(\mathbb{R})$ into $\mathbb{R}^3$ as the cross-cap. Here’s an image of it from his 1966-67 seminar on ‘Logique du fantasme’ (213 pages).

This image includes the position of the objet petit $a$ as the end point of the self-intersection curve, which itself is referred to as the ‘castration’, or the ‘phallus’, or whatever.

Brace yourself for the ‘explanation’ of $\$~\diamond~a$: if you walk twice around $a$ this divides the cross-cap into a disk and a Mobius-strip!

The mathematics is correct but I fail to see how this helps the psycho-analyst in her therapy. But hey, everyone will tell you I have absolutely no therapeutic talent.

Let’s return to the brand new book by Alain Connes and Patrick Gauthier-Lafaye: “A l’ombre de Grothendieck et de Lacan, un topos sur l’inconscient”.

It was to be expected that they would defend Lacan’s exploitation of (surface) topology by saying that he was just unfortunate not to have the more general notion of toposes available, as well as their much subtler logic. Perhaps someone should write a fictional parody on Greenshields book: “Lacan and the topos”…

Connes’ first attempt to construct the topos of unconsciousness was also not much of a surprise. According to Lacan the unconscious is ‘structured like a language’.

So, a natural approach might be to start with a ‘dictionary’-category (words and relations between them) or any other known use of a category in linguistics. A good starting point to read up on this is the blog post A new application of category theory in linguistics.

Eventually they settled for a much more ambitious project. To Connes and Gauthier-Lafaye every individual has her own topos and corresponding logic.

They don’t specify how to construct these individual toposes, but postulate that they are all connected to a classifying topos, which is their incarnation of the world of ‘myths’ and ‘fantasies’.

Surely an idea Lacan would have liked. Underlying the unconscious must be, according to Connes and Gauthier-Lafaye, a geometric theory! That is, it can be fully described by first order sentences.

Lacan himself used already some first order sequences in his teachings, such as in his logic of sexuation:

\[

\forall x~(\Phi~x)~\quad \text{but also} \quad \exists x~\neg~(\Phi~x) \]

where $\Phi~x$ is the phallic function. Quoting from Greenshield’s book:

“While all (the sons) are subject to ($\forall x$) the law of castration ($\Phi~x$), we also learn that this law nevertheless resides upon an exception: there exists a subject ($\exists x$) that is not subject to this law ($\neg \Phi~x$). This exception is embodied by the despotic father who, not being subject to the phallic function, experiences an impossible mode of totalised jouissance (he enjoys all the women). He is, quite simply, the exception that proves the law a necessary beyond that enables the law’s geometric bounds to be defined.”

It will be quite hard (but probably great fun for psycho-analysts) to turn the whole of Lacanian theory on the unconscious into a coherent geometric theory, construct its classifying topos, and apply the Joyal-Reyes theorem to get at the individual cases/toposes.

I’m sure there are much deeper insights to be gained from Connes’ and Gauthier-Lafaye’s book, but this is what i got from a first, fast, cursory reading of it.

Leave a Comment