There are only a handful of human activities where one goes to extraordinary lengths to keep a dream alive, in spite of overwhelming evidence : religion, theoretical physics, supporting the Belgian football team and … mathematics.

In recent years several people spend a lot of energy looking for properties of an elusive object : the field with one element $\mathbb{F}_1 $, or in French : “F-un”. The topic must have reached a level of maturity as there was a conference dedicated entirely to it : NONCOMMUTATIVE GEOMETRY AND GEOMETRY OVER THE FIELD WITH ONE ELEMENT.

In this series I’d like to find out what the fuss is all about, why people would like it to exist and what it has to do with noncommutative geometry. However, before we start two remarks :

The field $\mathbb{F}_1 $ does not exist, so don’t try to make sense of sentences such as “The ‘field with one element’ is the free algebraic monad generated by one constant (p.26), or the universal generalized ring with zero (p.33)” in the wikipedia-entry. The simplest proof is that in any (unitary) ring we have $0 \not= 1 $ so any ring must contain at least two elements. A more highbrow version : the ring of integers $\mathbb{Z} $ is the initial object in the category of unitary rings, so it cannot be an algebra over anything else.

The second remark is that several people have already written blog-posts about $\mathbb{F}_1 $. Here are a few I know of : David Corfield at the n-category cafe and at his old blog, Noah Snyder at the secret blogging seminar, Kea at the Arcadian functor, AC and K. Consani at Noncommutative geometry and John Baez wrote about it in his weekly finds.

The dream we like to keep alive is that we will prove the Riemann hypothesis one fine day by lifting Weil’s proof of it in the case of curves over finite fields to rings of integers.

The dream we like to keep alive is that we will prove the Riemann hypothesis one fine day by lifting Weil’s proof of it in the case of curves over finite fields to rings of integers.

Even if you don’t know a word about Weil’s method, if you think about it for a couple of minutes, there are two immediate formidable problems with this strategy.

For most people this would be evidence enough to discard the approach, but, we mathematicians have found extremely clever ways for going into denial.

The first problem is that if we want to think of $\mathbf{spec}(\mathbb{Z}) $ (or rather its completion adding the infinite place) as a curve over some field, then $\mathbb{Z} $ must be an algebra over this field. However, no such field can exist…

No problem! If there is no such field, let us invent one, and call it $\mathbb{F}_1 $. But, it is a bit hard to do geometry over an illusory field. Christophe Soule succeeded in defining varieties over $\mathbb{F}_1 $ in a talk at the 1999 Arbeitstagung and in a more recent write-up of it : Les varietes sur le corps a un element.

No problem! If there is no such field, let us invent one, and call it $\mathbb{F}_1 $. But, it is a bit hard to do geometry over an illusory field. Christophe Soule succeeded in defining varieties over $\mathbb{F}_1 $ in a talk at the 1999 Arbeitstagung and in a more recent write-up of it : Les varietes sur le corps a un element.

We will come back to this in more detail later, but for now, here’s the main idea. Consider an existent field $k $ and an algebra $k \rightarrow R $ over it. Now study the properties of the functor (extension of scalars) from $k $-schemes to $R $-schemes. Even if there is no morphism $\mathbb{F}_1 \rightarrow \mathbb{Z} $, let us assume it exists and define $\mathbb{F}_1 $-varieties by requiring that these guys should satisfy the properties found before for extension of scalars on schemes defined over a field by going to schemes over an algebra (in this case, $\mathbb{Z} $-schemes). Roughly speaking this defines $\mathbb{F}_1 $-schemes as subsets of points of suitable $\mathbb{Z} $-schemes.

But, this is just one half of the story. He adds to such an $\mathbb{F}_1 $-variety extra topological data ‘at infinity’, an idea he attributes to J.-B. Bost. This added feature is a $\mathbb{C} $-algebra $\mathcal{A}_X $, which does not necessarily have to be commutative. He only writes : “Par ignorance, nous resterons tres evasifs sur les proprietes requises sur cette $\mathbb{C} $-algebre.”

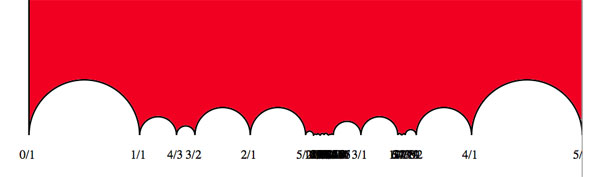

The algebra $\mathcal{A}_X $ originates from trying to bypass the second major obstacle with the Weil-Riemann-strategy. On a smooth projective curve all points look similar as is clear for example by noting that the completions of all local rings are isomorphic to the formal power series $k[[x]] $ over the basefield, in particular there is no distinction between ‘finite’ points and those lying at ‘infinity’.

The algebra $\mathcal{A}_X $ originates from trying to bypass the second major obstacle with the Weil-Riemann-strategy. On a smooth projective curve all points look similar as is clear for example by noting that the completions of all local rings are isomorphic to the formal power series $k[[x]] $ over the basefield, in particular there is no distinction between ‘finite’ points and those lying at ‘infinity’.

The completions of the local rings of points in $\mathbf{spec}(\mathbb{Z}) $ on the other hand are completely different, for example, they have residue fields of different characteristics… Still, local class field theory asserts that their quotient fields have several common features. For example, their Brauer groups are all isomorphic to $\mathbb{Q}/\mathbb{Z} $. However, as $Br(\mathbb{R}) = \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z} $ and $Br(\mathbb{C}) = 0 $, even then there would be a clear distinction between the finite primes and the place at infinity…

Alain Connes came up with an extremely elegant solution to bypass this problem in Noncommutative geometry and the Riemann zeta function. He proposes to replace finite dimensional central simple algebras in the definition of the Brauer group by AF (for Approximately Finite dimensional)-central simple algebras over $\mathbb{C} $. This is the origin and the importance of the Bost-Connes algebra.

We will come back to most of this in more detail later, but for the impatient, Connes has written a paper together with Caterina Consani and Matilde Marcolli Fun with $\mathbb{F}_1 $ relating the Bost-Connes algebra to the field with one element.

6 Comments