There were some great comments by Peter before this post was taken offline. So, here they are, once again.

4 CommentsTag: bourbaki

If Bourbaki=WikiLeaks then Weil=Assange

Published May 17, 2011 by lievenlb

In an interview with readers of the Guardian, December 3rd 2010, Julian Assange made a somewhat surprising comparison between WikiLeaks and Bourbaki, sorry, The Bourbaki (sic) :

“I originally tried hard for the organisation to have no face, because I wanted egos to play no part in our activities. This followed the tradition of the French anonymous pure mathematians, who wrote under the collective allonym, “The Bourbaki”. However this quickly led to tremendous distracting curiosity about who and random individuals claiming to represent us. In the end, someone must be responsible to the public and only a leadership that is willing to be publicly courageous can genuinely suggest that sources take risks for the greater good. In that process, I have become the lightening rod. I get undue attacks on every aspect of my life, but then I also get undue credit as some kind of balancing force.”

Analogies are never perfect, but perhaps Assange should have taken it a bit further and studied the history of the pre-war Bourbakistas in order to avoid problems that led to the eventual split-up.

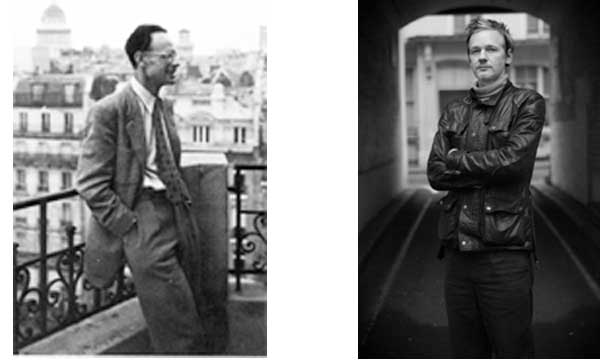

Clearly, if Bourbaki=WikiLeaks, then Assange plays the role of Andre Weil. Both of them charismatic leaders, convincing the group around them that for the job at hand to succeed, it is best to work as a collective so that individual contributions cannot be traced.

At first this works well. Both groups make progress and gain importance, also to the outside world. But then, internal problems surface, questioning the commitment of ‘the leader’ to the original project.

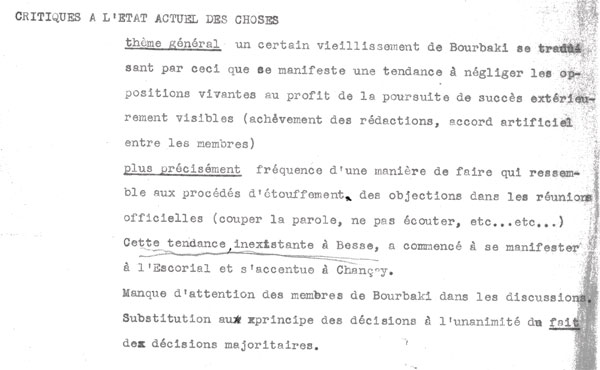

In the case of the Bourbakis, Claude Chevalley and Rene de Possel dropped that bombshell at the second Chancay-meeting in 1937 with a 2 page pamphlet 7 theses de Chancay.

“Criticism on the state of affairs :

- in general, a certain aging of Bourbaki, which manifests itself in a tendency to neglect internal lively opposition in favor of pursuing visible external succes ((failed) completion of versions, artificial agreement among members of the group).

- in particular, often the working method appears to be that of suffocating any objections in official meetings (via interruptions, not listening, etc. etc.). This tendency didn’t exist at the Besse meeting, began to manifest itself at the Escorial-meeting and got even worse here at Chancay. Bourbaki-members don’t pay attention to discussions and the principle of unanimous decision-making is replaced in reality by majority rule.”

Sounds familiar? Perhaps stretching the analogy a bit one might say that Claude Chevalley’s and Rene de Possel’s role within Bourbaki is similar to that of respectively Birgitta Jónsdóttir and Daniel Domscheit-Berg within WikiLeaks.

This criticism will be neglected and at the following Bourbaki-meeting in Dieulefit (neither Chevalley nor de Possel were present) hardly any work gets done, largely due to the fact that Andre Weil is more concerned about his personal safety and escapes during the meeting for a couple of days to Switserland, fearing an imminent invasion.

After the Dieulefit-meeting, even though Bourbaki’s fame is spreading, work on the manuscripts is halted because all members are reserve-officers in the French army and have to prepare for war.

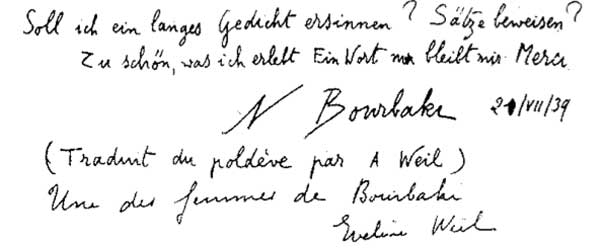

Except for Andre Weil, who’s touring the world with a clear “Bourbaki, c’est moi!” message, handing out Bourbaki name-cards or invitations to Betti Bourbaki’s wedding… That Andre and Eveline Weil are traveling as Mr. and Mrs. Bourbaki is perhaps best illustrated by the thank-you note, left on their journey through Finland.

If it were not for the fact that the other members had more pressing matters to deal with, Weil’s attitude would have resulted in more people dropping out of the group, or continuing the work under another name, a bit like what happens to WikiLeaks and OpenLeaks today.

Leave a CommentWhat happened on the Bourbaki wedding day?

Published May 15, 2011 by lievenlb

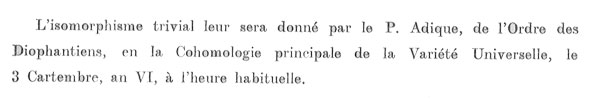

Early on in this series we deciphered part of the Bourbaki wedding invitation

The wedding was planned on “le 3 Cartembre, an VI” or, for non-Bourbakistas, June 3rd 1939. But, why did they choose that particular day?

Because the wedding-invitation-joke was concocted sometime between mid april and mid may 1939, the most probable explanation clearly is that they took a calendar and scheduled their fake wedding on a saturday not too far in the future.

Or, could it be that the invitation indeed contained a coded message pointing to an important event (at least as far as Bourbaki or the Weils were concerned) taking place in Paris on June 3rd 1939?

Unlikely? Well, what about this story:

André Malraux was a French writer and later statesman. He was noted especially for his novel La Condition Humaine (1933).

André Malraux was a French writer and later statesman. He was noted especially for his novel La Condition Humaine (1933).

During the 1930s, Malraux was active in the anti-fascist Popular Front in France. At the beginning of the Spanish Civil War he joined the Republican forces in Spain, serving in and helping to organize the small Spanish Republican Air Force. The Republic government circulated photos of Malraux’s standing next to some Potez 540 bombers suggesting that France was on their side, at a time when France and the United Kingdom had declared official neutrality.

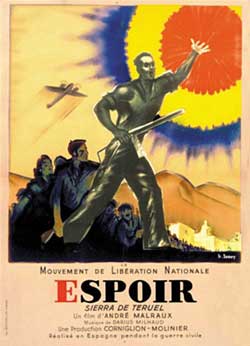

In 1938 he published L’Espoir, a novel influenced by his Spanish war experiences. In the same year, Malraux and Boris Peskine produced a movie based on the book, filmed in Spain (in Tarragon, Collbató and Montserrat) : sierra de Teruel (later called, L’Espoir)

This wikipedia-page claims that the movie was released June 13th, 1945. But this isn’t quite correct.

This wikipedia-page claims that the movie was released June 13th, 1945. But this isn’t quite correct.

The first (private) viewing of the film took place … on saturday june 3rd, 1939.

In august 1939 there was another private viewing for the Spanish Government-in-Exile, and Malraux wanted the public release to take place in september. However, after the invasion by Hitler of Poland and considerable pressure of the French amassador to Madrid, Philippe Petain, the distribution of the movie was forbidden by the government of Edouard Daladier IV.

For this reason the public release had to be postponed until after the war.

But let us return to the first viewing on Bourbaki’s wedding day. We know that a lot of authors were present. There’s evidence that Simone de Beauvoir attended and quite likely so did Simone Weil, Andre’s sister.

In 1936, despite her professed pacifism, Simone Weil fought in the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side. She identified herself as an anarchist and joined the Sébastien Faure Century, the French-speaking section of the anarchist militia.

According to her biography (p. 473) she was still in contact with Malraux and, at the time, tried in vain to convince him of the fact that the Stalin-regime was as oppressive as the fascist-regimes. So, it is quite likely she was invited to the viewing, or at least knew about it.

From Andre Weil’s auto-biography we know that letters (and even telegrams) were exchanged between him and his sister, when he was in England in the spring of 1939. So, it is quite likely that she told him about the Malraux-Sierra de Tenuel happening (see also the Escorial post).

According to the invitation the Bourbaki-wedding took place “en la Cohomologie Principale”. The private viewing of Malraux’ film took place in “Cinéma Le Paris” on the Champs Elysées.

Could it be that “Cohomologie Principale”=”Cinema Le Paris”?

Leave a Comment