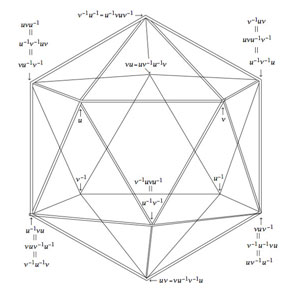

While the verdict on a neolithic Scottish icosahedron is still open, let us recall Kostant’s group-theoretic construction of the icosahedron from its rotation-symmetry group $A_5 $.

The alternating group $A_5 $ has two conjugacy classes of order 5 elements, both consisting of exactly 12 elements. Fix one of these conjugacy classes, say $C $ and construct a graph with vertices the 12 elements of $C $ and an edge between two $u,v \in C $ if and only if the group-product $u.v \in C $ still belongs to the same conjugacy class.

The alternating group $A_5 $ has two conjugacy classes of order 5 elements, both consisting of exactly 12 elements. Fix one of these conjugacy classes, say $C $ and construct a graph with vertices the 12 elements of $C $ and an edge between two $u,v \in C $ if and only if the group-product $u.v \in C $ still belongs to the same conjugacy class.

Observe that this relation is symmetric as from $u.v = w \in C $ it follows that $v.u=u^{-1}.u.v.u = u^{-1}.w.u \in C $. The graph obtained is the icosahedron, depicted on the right with vertices written as words in two adjacent elements u and v from $C $, as indicated.

Kostant writes : “Normally it is not a common practice in group theory to consider whether or not the product of two elements in a conjugacy class is again an element in that conjugacy class. However such a consideration here turns out to be quite productive.”

Still, similar constructions have been used in other groups as well, in particular in the study of the largest sporadic group, the monster group $\mathbb{M} $.

There is one important catch. Whereas it is quite trivial to multiply two permutations and verify whether the result is among 12 given ones, for most of us mortals it is impossible to do actual calculations in the monster. So, we’d better have an alternative way to get at the icosahedral graph using only $A_5 $-data that is also available for the monster group, such as its character table.

Let $G $ be any finite group and consider three of its conjugacy classes $C(i),C(j) $ and $C(k) $. For any element $w \in C(k) $ we can compute from the character table of $G $ the number of different products $u.v = w $ such that $u \in C(i) $ and $v \in C(j) $. This number is given by the formula

$\frac{|G|}{|C_G(g_i)||C_G(g_j)|} \sum_{\chi} \frac{\chi(g_i) \chi(g_j) \overline{\chi(g_k)}}{\chi(1)} $

where the sum is taken over all irreducible characters $\chi $ and where $g_i \in C(i),g_j \in C(j) $ and $g_k \in C(k) $. Note also that $|C_G(g)| $ is the number of $G $-elements commuting with $g $ and that this number is the order of $G $ divided by the number of elements in the conjugacy class of $g $.

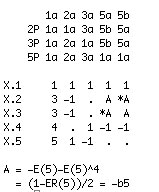

The character table of $A_5 $ is given on the left : the five columns correspond to the different conjugacy classes of elements of order resp. 1,2,3,5 and 5 and the rows are the character functions of the 5 irreducible representations of dimensions 1,3,3,4 and 5.

The character table of $A_5 $ is given on the left : the five columns correspond to the different conjugacy classes of elements of order resp. 1,2,3,5 and 5 and the rows are the character functions of the 5 irreducible representations of dimensions 1,3,3,4 and 5.

Let us fix the 4th conjugacy class, that is 5a, as our class $C $. By the general formula, for a fixed $w \in C $ the number of different products $u.v=w $ with $u,v \in C $ is equal to

$\frac{60}{25}(\frac{1}{1} + \frac{(\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2})^3}{3} + \frac{(\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2})^3}{3} – \frac{1}{4} + \frac{0}{5}) = \frac{60}{25}(1 + \frac{4}{3} – \frac{1}{4}) = 5 $

Because for each $x \in C $ also its inverse $x^{-1} \in C $, this can be rephrased by saying that there are exactly 5 different products $w^{-1}.u \in C $, or equivalently, that the valency of every vertex $w^{-1} \in C $ in the graph is exactly 5.

That is, our graph has 12 vertices, each with exactly 5 neighbors, and with a bit of extra work one can show it to be the icosahedral graph.

For the monster group, the Atlas tells us that it has exactly 194 irreducible representations (and hence also 194 conjugacy classes). Of these conjugacy classes, the involutions (that is the elements of order 2) are of particular importance.

There are exactly 2 conjugacy classes of involutions, usually denoted 2A and 2B. Involutions in class 2A are called “Fischer-involutions”, after Bernd Fischer, because their centralizer subgroup is an extension of Fischer’s baby Monster sporadic group.

There are exactly 2 conjugacy classes of involutions, usually denoted 2A and 2B. Involutions in class 2A are called “Fischer-involutions”, after Bernd Fischer, because their centralizer subgroup is an extension of Fischer’s baby Monster sporadic group.

Likewise, involutions in class 2B are usually called “Conway-involutions” because their centralizer subgroup is an extension of the largest Conway sporadic group.

Let us define the monster graph to be the graph having as its vertices the Fischer-involutions and with an edge between two of them $u,v \in 2A $ if and only if their product $u.v $ is again a Fischer-involution.

Because the centralizer subgroup is $2.\mathbb{B} $, the number of vertices is equal to $97239461142009186000 = 2^4 * 3^7 * 5^3 * 7^4 * 11 * 13^2 * 29 * 41 * 59 * 71 $.

From the general result recalled before we have that the valency in all vertices is equal and to determine it we have to use the character table of the monster and the formula. Fortunately GAP provides the function ClassMultiplicationCoefficient to do this without making errors.

gap> table:=CharacterTable("M");

CharacterTable( "M" )

gap> ClassMultiplicationCoefficient(table,2,2,2);

27143910000

Perhaps noticeable is the fact that the prime decomposition of the valency $27143910000 = 2^4 * 3^4 * 5^4 * 23 * 31 * 47 $ is symmetric in the three smallest and three largest prime factors of the baby monster order.

Robert Griess proved that one can recover the monster group $\mathbb{M} $ from the monster graph as its automorphism group!

As in the case of the icosahedral graph, the number of vertices and their common valency does not determine the monster graph uniquely. To gain more insight, we would like to know more about the sizes of minimal circuits in the graph, the number of such minimal circuits going through a fixed vertex, and so on.

As in the case of the icosahedral graph, the number of vertices and their common valency does not determine the monster graph uniquely. To gain more insight, we would like to know more about the sizes of minimal circuits in the graph, the number of such minimal circuits going through a fixed vertex, and so on.

Such an investigation quickly leads to a careful analysis which other elements can be obtained from products $u.v $ of two Fischer involutions $u,v \in 2A $. We are in for a major surprise, first observed by John McKay:

Printing out the number of products of two Fischer-involutions giving an element in the i-th conjugacy class of the monster,

where i runs over all 194 possible classes, we get the following string of numbers :

97239461142009186000, 27143910000, 196560, 920808, 0, 3, 1104, 4, 0, 0, 5, 0,

6, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

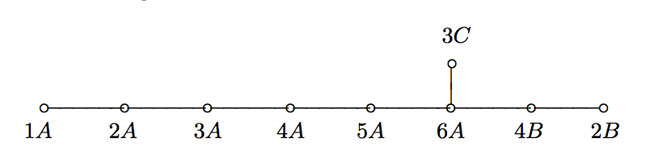

That is, the elements of only 9 conjugacy classes can be written as products of two Fischer-involutions! These classes are :

- 1A = { 1 } written in 97239461142009186000 different ways (after all involutions have order two)

- 2A, each element of which can be written in exactly 27143910000 different ways (the valency)

- 2B, each element of which can be written in exactly 196560 different ways. Observe that this is the kissing number of the Leech lattice leading to a permutation representation of $2.Co_1 $.

- 3A, each element of which can be written in exactly 920808 ways. Note that this number gives a permutation representation of the maximal monster subgroup $3.Fi_{24}’ $.

- 3C, each element of which can be written in exactly 3 ways.

- 4A, each element of which can be written in exactly 1104 ways.

- 4B, each element of which can be written in exactly 4 ways.

- 5A, each element of which can be written in exactly 5 ways.

- 6A, each element of which can be written in exactly 6 ways.

Let us forget about the actual numbers for the moment and concentrate on the orders of these 9 conjugacy classes : 1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,6. These are precisely the components of the fundamental root of the extended Dynkin diagram $\tilde{E_8} $!

This is the content of John McKay’s E(8)-observation : there should be a precise relation between the nodes of the extended Dynkin diagram and these 9 conjugacy classes in such a way that the order of the class corresponds to the component of the fundamental root. More precisely, one conjectures the following correspondence

This is similar to the classical McKay correspondence between finite subgroups of $SU(2) $ and extended Dynkin diagrams (the binary icosahedral group corresponding to extended E(8)). In that correspondence, the nodes of the Dynkin diagram correspond to irreducible representations of the group and the edges are determined by the decompositions of tensor-products with the fundamental 2-dimensional representation.

Here, however, the nodes have to correspond to conjugacy classes (rather than representations) and we have to look for another procedure to arrive at the required edges! An exciting proposal has been put forward recently by John Duncan in his paper Arithmetic groups and the affine E8 Dynkin diagram.

It will take us a couple of posts to get there, but for now, let’s give the gist of it : monstrous moonshine gives a correspondence between conjugacy classes of the monster and certain arithmetic subgroups of $PSL_2(\mathbb{R}) $ commensurable with the modular group $\Gamma = PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $. The edges of the extended Dynkin E(8) diagram are then given by the configuration of the arithmetic groups corresponding to the indicated 9 conjugacy classes! (to be continued…)

Leave a Comment