Here’s a tiny problem illustrating our limited knowledge of finite fields : “Imagine an infinite queue of Knights ${ K_1,K_2,K_3,\ldots } $, waiting to be seated at the unit-circular table. The master of ceremony (that is, you) must give Knights $K_a $ and $K_b $ a place at an odd root of unity, say $\omega_a $ and $\omega_b $, such that the seat at the odd root of unity $\omega_a \times \omega_b $ must be given to the Knight $K_{a \otimes b} $, where $a \otimes b $ is the Nim-multiplication of $a $ and $b $. Which place would you offer to Knight $K_{16} $, or Knight $K_n $, or, if you’re into ordinals, Knight $K_{\omega} $?”

What does this have to do with finite fields? Well, consider the simplest of all finite field $\mathbb{F}_2 = { 0,1 } $ and consider its algebraic closure $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $. Last year, we’ve run a series starting here, identifying the field $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $, following John H. Conway in ONAG, with the set of all ordinals smaller than $\omega^{\omega^{\omega}} $, given the Nim addition and multiplication. I know that ordinal numbers may be intimidating at first, so let’s just restrict to ordinary natural numbers for now. The Nim-addition of two numbers $n \oplus m $ can be calculated by writing the numbers n and m in binary form and add them without carrying. For example, $9 \oplus 1 = 1001+1 = 1000 = 8 $. Nim-multiplication is slightly more complicated and is best expressed using the so-called Fermat-powers $F_n = 2^{2^n} $. We then demand that $F_n \otimes m = F_n \times m $ whenever $m < F_n $ and $F_n \otimes F_n = \frac{3}{2}F_n $. Distributivity wrt. $\oplus $ can then be used to calculate arbitrary Nim-products. For example, $8 \otimes 3 = (4 \otimes 2) \otimes (2 \oplus 1) = (4 \otimes 3) \oplus (4 \otimes 2) = 12 \oplus 8 = 4 $. Conway’s remarkable result asserts that the ordinal numbers, equipped with Nim addition and multiplication, form an algebraically closed field of characteristic two. The closure $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ is identified with the subfield of all ordinals smaller than $\omega^{\omega^{\omega}} $. For those of you who don’t feel like going transfinite, the subfield $~(\mathbb{N},\oplus,\otimes) $ is identified with the quadratic closure of $\mathbb{F}_2 $.

The connection between $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ and the odd roots of unity has been advocated by Alain Connes in his talk before a general public at the IHES : “L’ange de la géométrie, le diable de l’algèbre et le corps à un élément” (the angel of geometry, the devil of algebra and the field with one element). He describes its content briefly in this YouTube-video

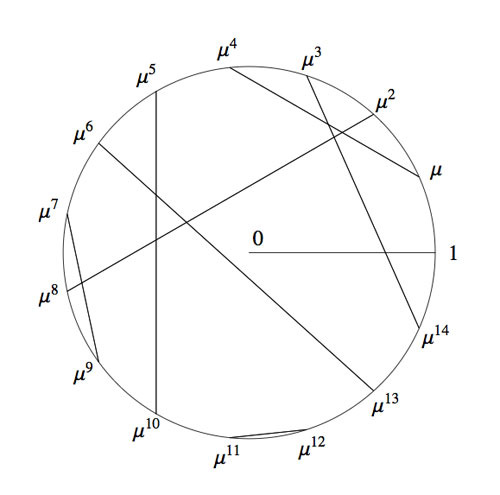

At first it was unclear to me which ‘coupling-problem’ Alain meant, but this has been clarified in his paper together with Caterina Consani Characteristic one, entropy and the absolute point. The non-zero elements of $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ can be identified with the set of all odd roots of unity. For, if x is such a unit, it belongs to a finite subfield of the form $\mathbb{F}_{2^n} $ for some n, and, as the group of units of any finite field is cyclic, x is an element of order $2^n-1 $. Hence, $\mathbb{F}_{2^n}- { 0 } $ can be identified with the set of $2^n-1 $-roots of unity, with $e^{2 \pi i/n} $ corresponding to a generator of the unit-group. So, all elements of $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ correspond to an odd root of unity. The observation that we get indeed all odd roots of unity may take you a couple of seconds (( If m is odd, then (2,m)=1 and so 2 is a unit in the finite cyclic group $~(\mathbb{Z}/m\mathbb{Z})^* $ whence $2^n = 1 (mod~m) $, so the m-roots of unity lie within those of order $2^n-1 $ )).

Assuming we succeed in fixing a one-to-one correspondence between the non-zero elements of $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ and the odd roots of unity $\mu_{odd} $ respecting multiplication, how can we recover the addition on $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $? Well, here’s Alain’s coupling function, he ties up an element x of the algebraic closure to the element s(x)=x+1 (and as we are in characteristic two, this is an involution, so also the element tied up to x+1 is s(x+1)=(x+1)+1=x. The clue being that multiplication together with the coupling map s allows us to compute any sum of two elements as $x+y=x \times s(\frac{y}{x}) = x \times (\frac{y}{x}+1) $.

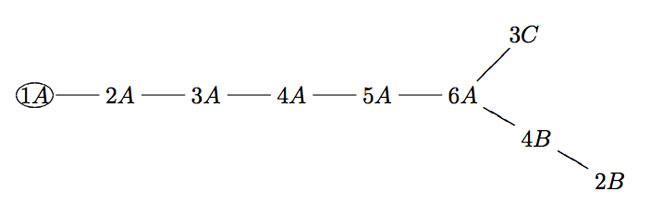

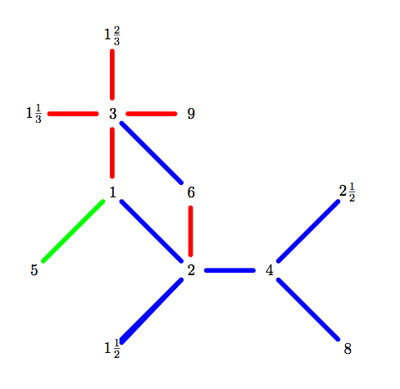

For example, all information about the finite field $\mathbb{F}_{2^4} $ is encoded in this identification with the 15-th roots of unity, together with the pairing s depicted as

Okay, we now have two identifications of the algebraic closure $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ : the smaller ordinals equipped with Nim addition and Nim multiplication and the odd roots of unity with complex-multiplication and the Connes-coupling s. The question we started from asks for a general recipe to identify these two approaches.

To those of you who are convinced that finite fields (LOL, even characteristic two!) are objects far too trivial to bother thinking about : as far as I know, NOBODY knows how to do this explicitly, even restricting the ordinals to merely the natural numbers!

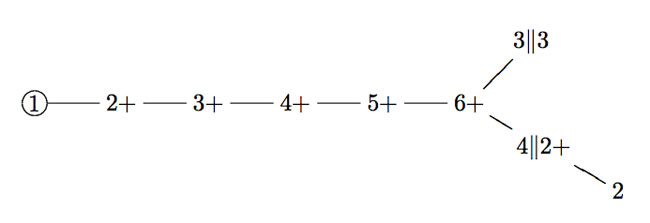

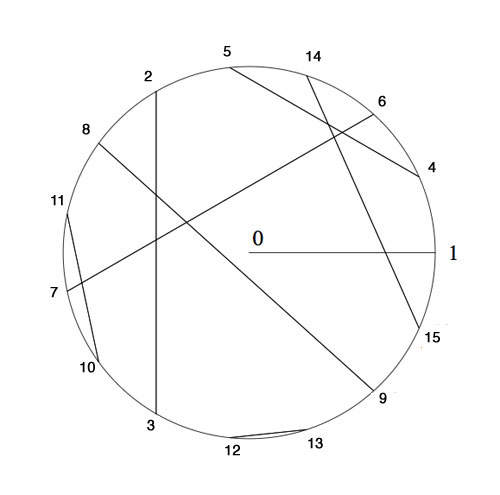

Please feel challenged! To get you started, I’ll show you how to place the first 15 Knights and give you a procedure (though far from explicit) to continue. Here’s the Nim-picture compatible with that above

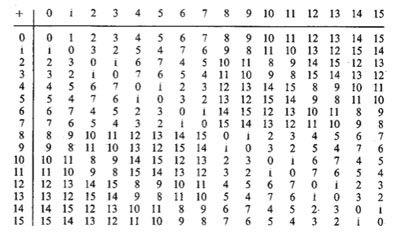

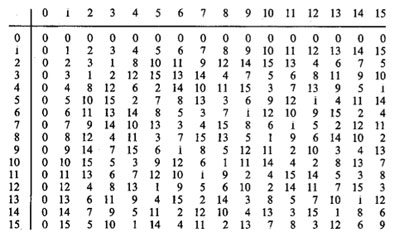

To verify this, and to illustrate the general strategy, I’d better hand you the Nim-tables of the first 16 numbers. Here they are

It is known that the finite subfields of $~(\mathbb{N},\oplus,\otimes) $ are precisely the sets of numbers smaller than the Fermat-powers $F_n $. So, the first one is all numbers smaller than $F_1=4 $ (check!). The smallest generator of the multiplicative group (of order 3) is 2, so we take this to correspond to the unit-root $e^{2 \pi i/3} $. The next subfield are all numbers smaller than $F_2 = 16 $ and its multiplicative group has order 15. Now, choose the smallest integer k which generates this group, compatible with the condition that $k^{\otimes 5}=2 $. Verify that this number is 4 and that this forces the identification and coupling given above.

The next finite subfield would consist of all natural numbers smaller than $F_3=256 $. Hence, in this field we are looking for the smallest number k generating the multiplicative group of order 255 satisfying the extra condition that $k^{\otimes 17}=4 $ which would fix an identification at that level. Then, the next level would be all numbers smaller than $F_4=65536 $ and again we would like to find the smallest number generating the multiplicative group and such that the appropriate power is equal to the aforementioned k, etc. etc.

Can you give explicit (even inductive) formulae to achieve this? I guess even the problem of placing Knight 16 will give you a couple of hours to think about… (to be continued).

Leave a Comment

This painting is among 32 works recently discovered and initially attributed to Pollock.

This painting is among 32 works recently discovered and initially attributed to Pollock.

Time to wrap up this series on

Time to wrap up this series on  They can be described using the mini-moonshine picture on the right. They are :

They can be described using the mini-moonshine picture on the right. They are :