In the first half of 1937, Andre Weil visited Princeton and introduced some of the postdocs present (notably Ralph Boas, John Tukey, and Frank Smithies) to Poldavian lore and Bourbaki’s early work.

In 1935, Bourbaki succeeded (via father Cartan) to get his paper “Sur un théorème de Carathéodory et la mesure dans les espaces topologiques” published in the Comptes Rendus des Séances Hebdomadaires de l’Académie des Sciences.

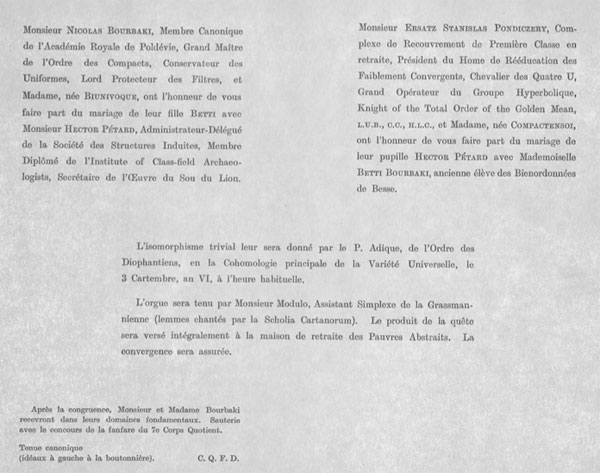

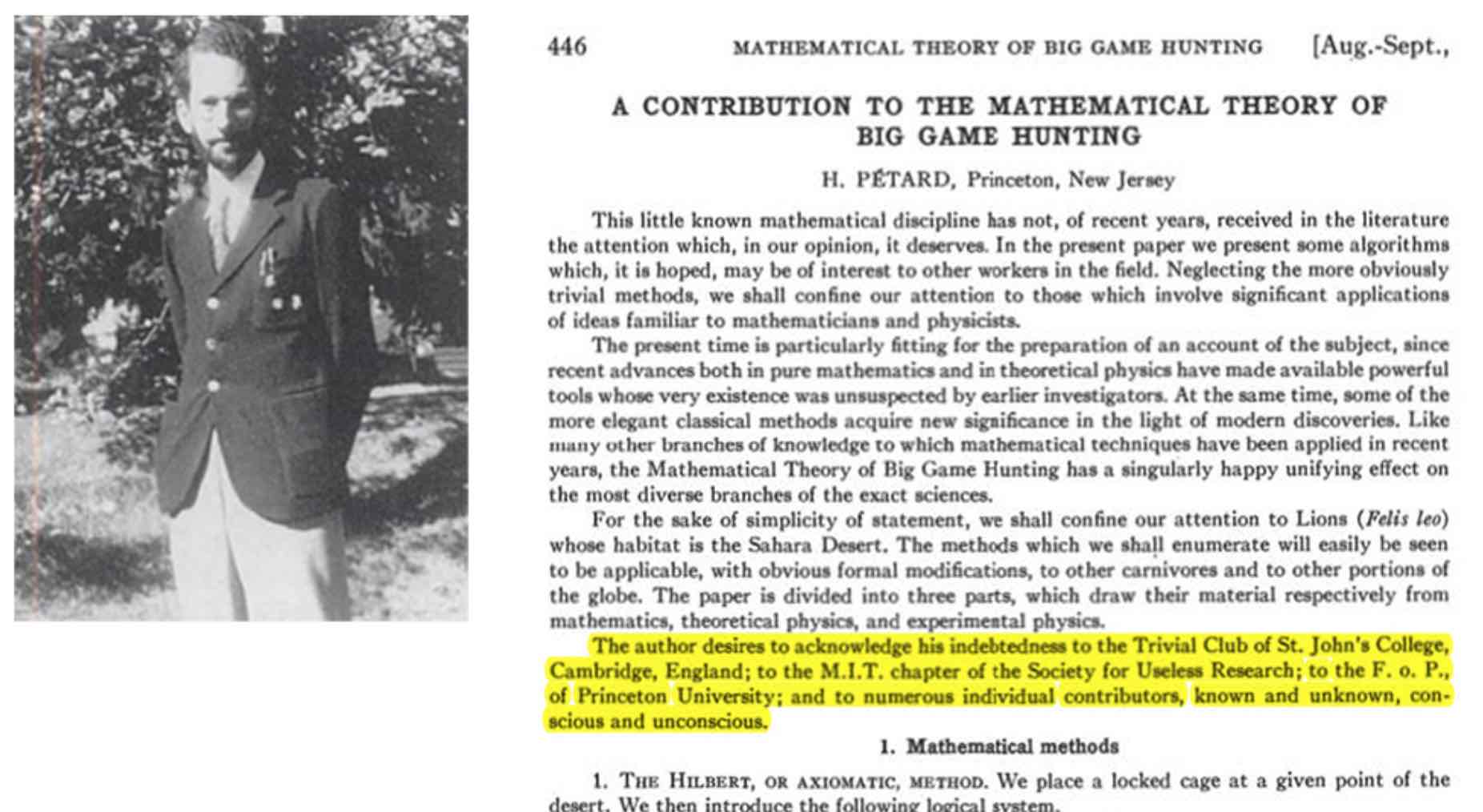

Inspired by this, the Princeton gang decided to try to get a compilation of their mathematical ways to catch a lion in the American Mathematical Monthly, under the pseudonym H. Petard, and accompanied by a cover letter signed by another pseudonym, E. S. Pondiczery.

By the time the paper “A contribution to the mathematical theory of big game hunting” appeared, Boas and Smithies were in cambridge pursuing their postdoc work, and Boas reported back to Tukey: “Pétard’s paper is attracting attention here,” generating “subdued chuckles … in the Philosophical Library.”

On the left, Ralph Boas in ‘official’ Pondiczery outfit – Photo Credit.

The acknowledgment of the paper is in true Bourbaki-canular style.

The author desires to acknowledge his indebtedness to the Trivial Club of St. John’s College, Cambridge, England; to the M.I.T. chapter of the Society for Useless Research; to the F. o. P., of Princeton University; and to numerous individual contributors, known and unknown, conscious and unconscious.

The Trivial Club of St. John’s College probably refers to the Adams Society, the St. John’s College mathematics society. Frank Smithies graduated from St. John’s in 1933, and began research on integral equations with Hardy. After his Ph. D., and on a Carnegie Fellowship and a St John’s College studentship, Smithies then spent two years at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, before returning back ‘home’.

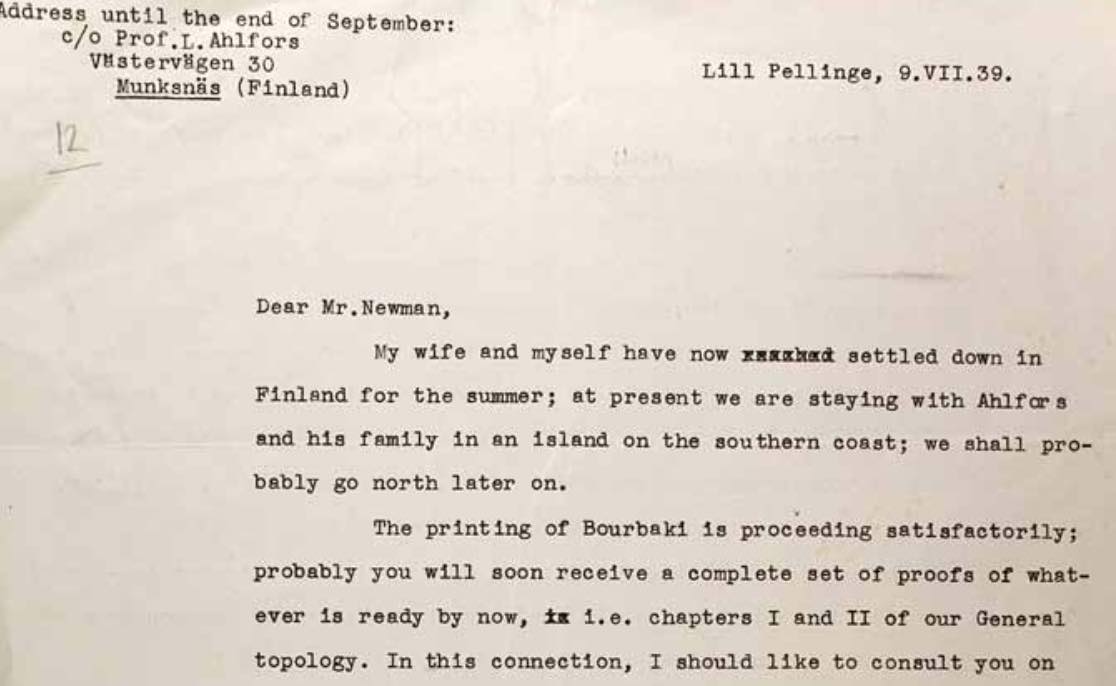

In the previous post, I assumed that Weil’s visit to Cambridge was linked to Trinity College. This should probably have been St. John’s College, his contact there being (apart from Smithies) Max Newman, a fellow of St. John’s. There are two letters from Weil (summer 1939, and summer 1940) in the Max Newman digital library.

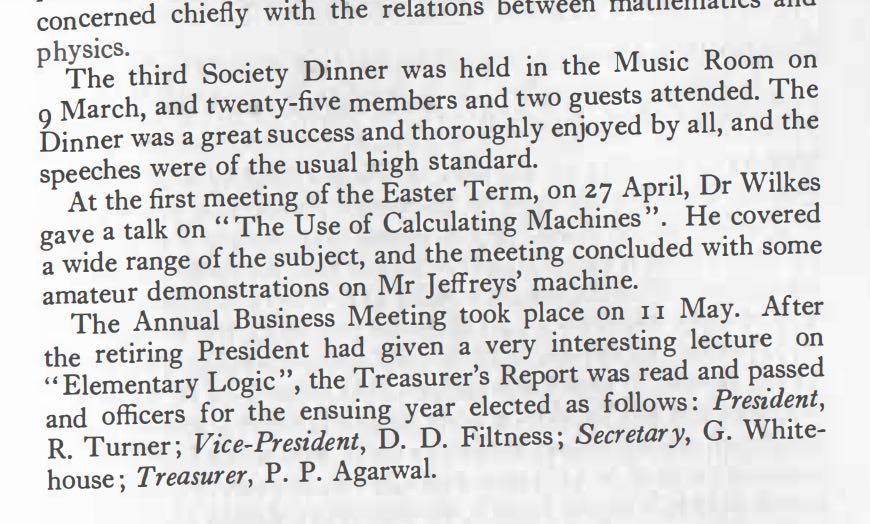

The Eagle Scanning Project is the online digital archive of The Eagle, the Journal of St. John’s College. Last time I wanted to find out what was going on, mathematically, in Cambridge in the spring of 1939. Now I know I just had to peruse the Easter 1939 and Michaelmas 1939 volumes of the Eagle, focussing on the reports of the Adams Society.

In the period Andre Weil was staying in Cambridge, they had a Society Dinner in the Music Room on March 9th, a talk about calculating machines (with demonstration!) on April 27th, and the Annual Business Meeting on May 11th, just two days before their punting trip to Grantchester,

The M.I.T. chapter of the Society for Useless Research is a different matter. The ‘Useless Research’ no doubt refers to Extrasensory Perception, or ESP. Pondiczery’s initials E. S. were chosen with a future pun in mind, as Tukey said in a later interview:

“Well, the hope was that at some point Ersatz Stanislaus Pondiczery at the Royal Institute of Poldavia was going to be able to sign something ESP RIP.”

What was the Princeton connection to ESP research?

Well, Joseph Banks Rhine conducted experiments at Duke University in the early 1930s on ESP using Zener cards. Amongst his test-persons was Hubert Pearce, who scored an overall 40% success rate, whereas chance would have been 20%.

Pearce and Joseph Banks Rhine (1932) – Photo Credit

In 1936, W. S. Cox tried to repeat Rhine’s experiment at Princeton University but failed. Cox concluded “There is no evidence of extrasensory perception either in the ‘average man’ or of the group investigated or in any particular individual of that group. The discrepancy between these results and those obtained by Rhine is due either to uncontrollable factors in experimental procedure or to the difference in the subjects.”

As to the ‘MIT chapter of the society for useless research’, a chapter usually refers to a fraternity at a University, but I couldn’t find a single one on the list of MIT fraternities involved in ESP, now or back in the late 1930s.

However, to my surprise I found that there is a MIT Archive of Useless Research, six boxes full of amazing books, pamphlets and other assorted ‘literature’ compiled between 1900 and 1940.

The Albert G. Ingalls pseudoscience collection (its official name) comprises collections of books and pamphlets assembled by Albert G. Ingalls while associate editor of Scientific American, and given to the MIT Libraries in 1940. Much of the material rejects contemporary theories of physical sciences, particularly theoretical and planetary physics; a smaller portion builds upon contemporary science and explores hypotheses not yet accepted.

I don’t know whether any ESP research is included in the collection, nor whether Boas and Tukey were aware of its existence in 1938, but it sure makes a good story.

The final riddle, the F. o. P., of Princeton University is an easy one. Of course, this refers to the “Friends of Pondiczery”, the circle of people in Princeton who knew of the existence of their very own Bourbaki.

Leave a Comment