Chasing one story, one sometimes tumbles into a different one. For some time I’m trying to debunk the story that Wolfgang Krull was close to inventing the notion of schemes in the early 1930’s.

I guess my first encounter with it was through The Rising Sea: Grothendieck

on simplicity and generality I by Colin McLarty which contains:

“From Emmy Noether’s viewpoint, then, it was natural to look at prime ideals instead of classical and generic points as we would more likely say today, to identify points with prime ideals. Her associate Wolfgang Krull did this. He gave a lecture in Paris before the Second World War on algebraic geometry taking all prime ideals as points, and using a Zariski topology. He did this over any ring, not only polynomial rings like $\mathbb{C}[x, y]$. The generality was obvious from the Noether viewpoint, since all the properties needed for the definition are common to all rings. The expert audience laughed at him and he abandoned the idea.”

The story seems to be due to Jurgen Neukirch’s ‘Erinnerungen an Wolfgang Krull’ published in ‘Wolfgang Krull : Gesammelte Abhandlungen’ (P. Ribenboim, editor).

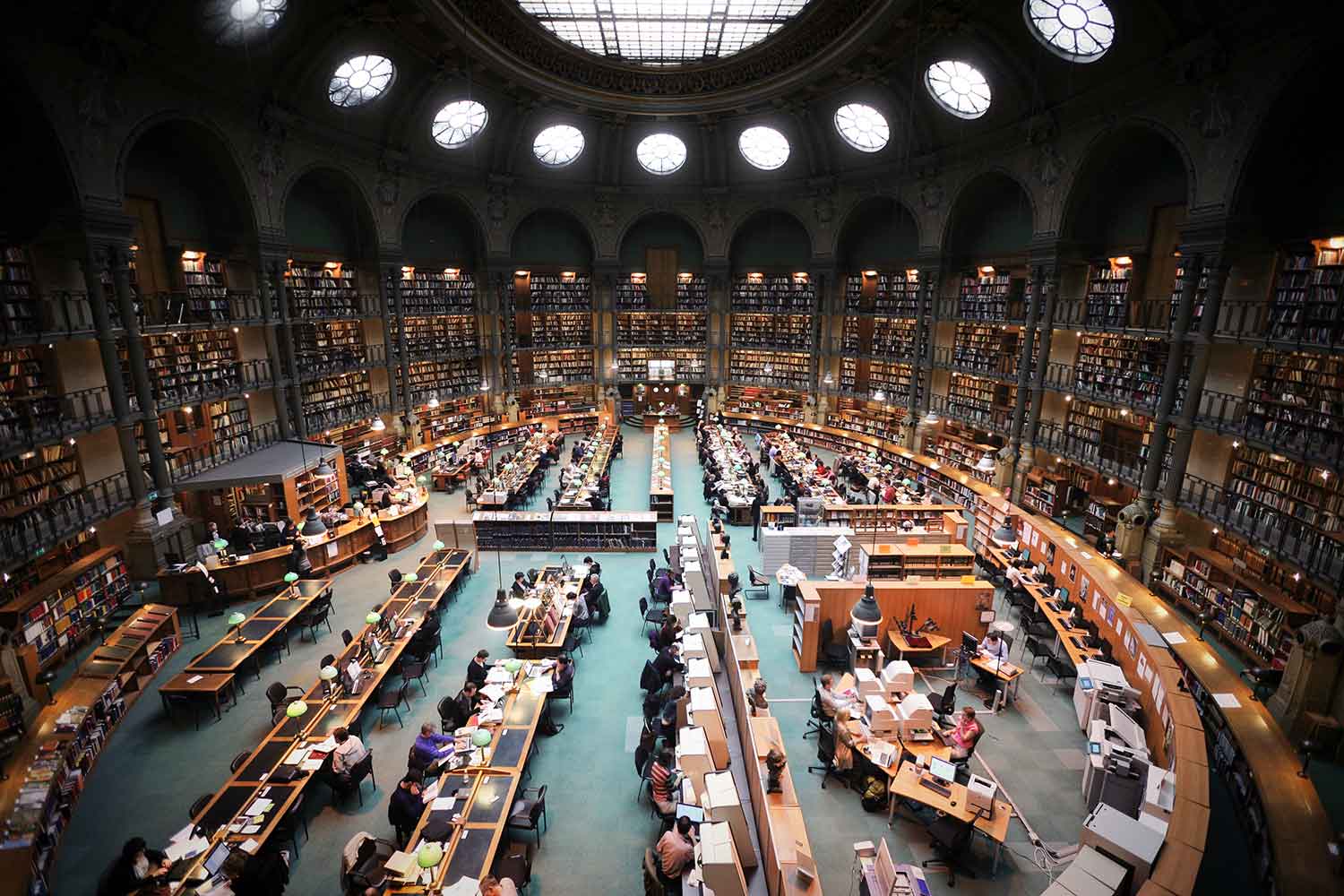

This rumour is quickly ruled out as Parisian pre-war mathematical life only involves the Hadamard- and Julia-seminars and they are very well documented.

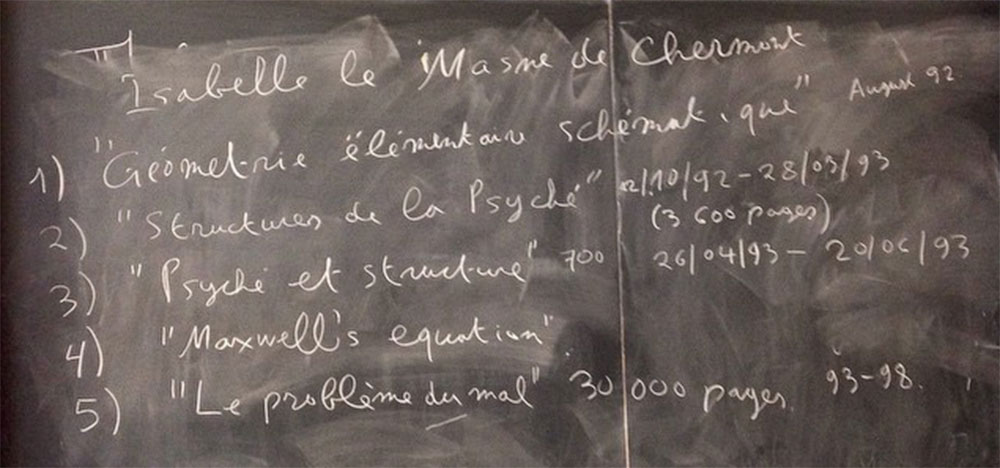

A more thorough investigation was carried out by Theo Raedschelders who contacted Karl-Otto Stöhr (a former student of Krull) and this is what he had to say about it:

“I remember that Prof. Krull once told to me, that in the early thirties he proposed in a talk that in algebraic geometry a larger number of points should be taken in consideration, namely points corresponding to the prime ideals of commutative rings. I always thought that this talk did happen at some place in Germany. He further mentioned that the mathematician Nöbeling in the audience argued that this idea would not be of any help to understand italian algebraic geometry.”

I had never heard of Nöbeling, so here’s where this story takes a turn…

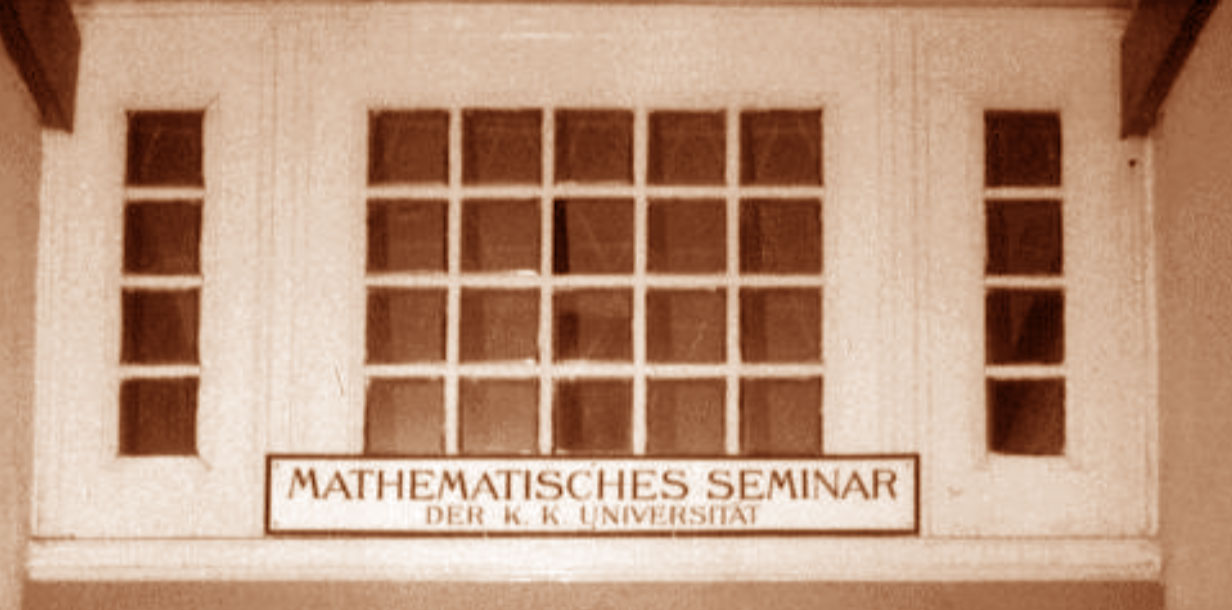

[section_title text=”The Vienna Mathematical Seminar”]

Wien 1938 und der Exodus der Mathematik is a fascinating account of Vienna mathematical life in the years leading up to WW2.

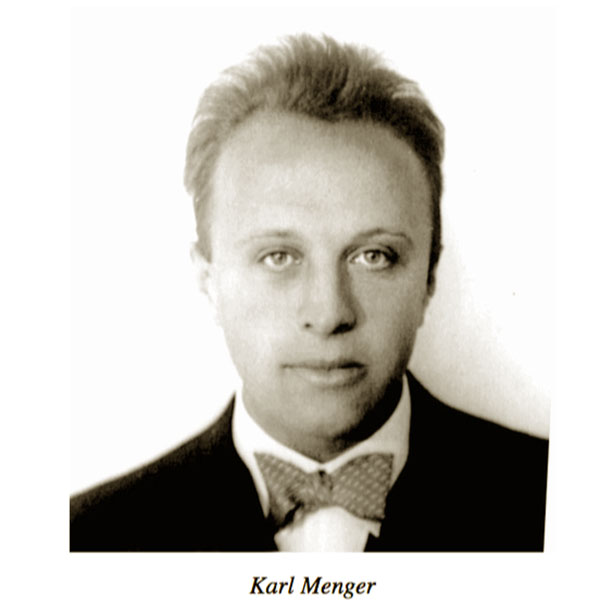

Karl menger was a central figure in the Vienna Mathematical Institute and founded its Mathematical Seminar. He gathered around him a brilliant group of young mathematicians including Kurt Gödel, Abraham Wald, Franz Alt and Olga Taussky.

Merger made important contributions to topology, including the “Menger sponge” and mathematical logic.

He seems to have been the first person to raise the idea of a point-free definition of the concept of topological space (aka ‘pointless topology’). In his 1928 book Dimensionstheorie, he defined the concept of space without referring to the points of an underlying set, but rather using pieces or, as he liked to say, “lumps”.

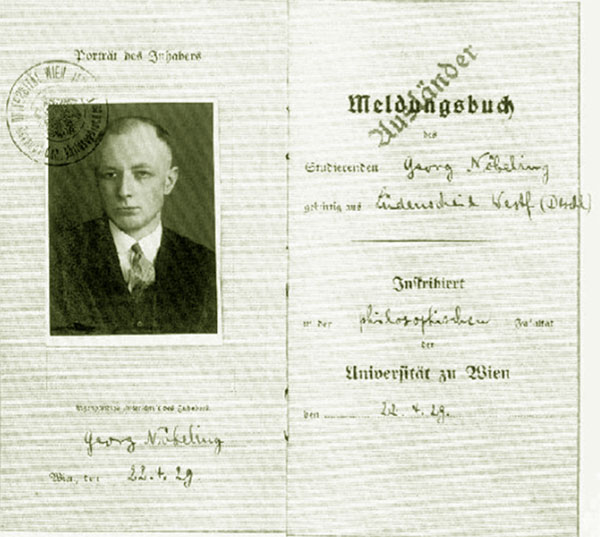

Georg Nöbeling was one of the first students and closest collaborators of Menger, finishing his Ph.D. in 1931 on a generalisation of Menger’s embedding problem.

In 1933 he moved to Erlangen, where Krull was a professor at the time. No doubt they discussed Krull’s invention of what we now know as the Zariski topology and Nöbeling may have said he didn’t believe it to be of any use in studying Italian geometry.

In Peter Johnstone’s historical account of the pre-history of topos theory The point of pointless topology there is no mention of Menger’s work. To him, the idea that points are secondary in a topological space required the prior development of lattice theory, which was developed in the mid 30-ties by Stone.

Stone’s lattice-theoretical approach to general topology found its final presentation in Georg Nöbeling’s 1954 book “Grundlagen der analytischen Topologie”. In fact, Nöbeling’s book could be seen as marking the end of the lattice-theoretical phase of pointless topology. A couple of years later locales and toposes where introduced.

So, did Nöbeling invent topos theory as some say Krull invented scheme theory? No, of course not, they both lacked the crucial ingredient of sheaf theory.

Still, it is fair to say that the Zariski topology was probably discovered by Krull in the early 30-ties and that Menger introduced ‘pointless topology’ in the late 20-ties, years ahead of the lattice-theoretic approach.

If you want to read more on this, please consult the paper by Mathieu Bélanger and Jean-Pierre MarquisMenger and Nöbeling on pointless topology.

Leave a Comment