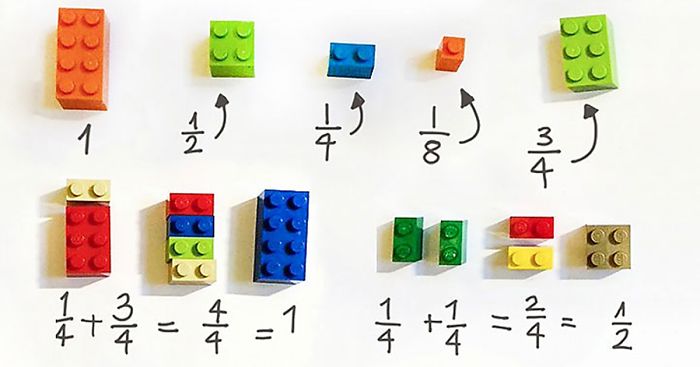

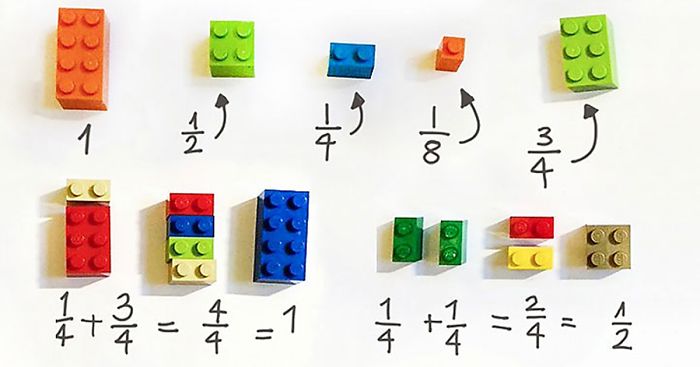

In 2001, Eugenia Cheng gave an interesting after-dinner talk Mathematics and Lego: the untold story. In it she compared math research to fooling around with lego. A quote:

“Lego: the universal toy. Enjoyed by people of all ages all over the place. The idea is simple and brilliant. Start with some basic blocks that can be joined together. Add creativity, imagination and a bit of ingenuity. Build anything.

Mathematics is exactly the same. We start with some basic building blocks and ways of joining them together. And then we use creativity, and, yes, imagination and certainly ingenuity, and try to build anything.”

She then goes on to explain category theory, higher dimensional topology, and the process of generalisation in mathematics, whole the time using lego as an analogy. But, she doesn’t get into the mathematics of lego, perhaps because the talk was aimed at students and researchers of all levels and all disciplines.

There are plenty of sites promoting lego in the teaching of elementary mathematics, here’s just one link-list-page: “27 Fantastic LEGO Math Learning Activities for All Ages”. I’m afraid ‘all ages’ here means: under 10…

Can one do better?

Everyone knows how to play with lego, which shapes you can build, and which shapes are simply impossible.

Can one tap into this subconscious geometric understanding to explain more advanced ideas such as symmetry, topological spaces, sheaves, categories, perhaps even topos theory… ?

Let’s continue our

[section_title text=”imaginary iterview”]

Question: What will be the opening scene of your book?

Alice posts a question on Lego-stackexchenge. She wants help to get hold of all imaginary lego shapes, including shapes impossible to construct in three-dimensional space, such as gluing two shapes over some internal common sub-shape, or Escher like constructions, and so on.

Question: And does she get help?

At first she only gets snide remarks, style: “brush off your French and wade through SGA4”.

Then, she’s advised to buy a large notebook and jot down whatever she can tell about shapes that one can construct.

If you think about this, you’ll soon figure out that you can only add new bricks along the upper or lower bricks of the shape. You may call these the boundary of the shape, and soon you’ll be doing topology, and forming coproducts.

These ‘legal’ lego shapes form what some of us would call a category, with a morphism from $A$ to $B$ for each different way one can embed shape $A$ into $B$.

Of course, one shouldn’t use this terminology, but rather speak of different instruction-manuals to get $B$ out of $A$ (the morphisms), stapling two sets of instructions together (the compositions), and the empty instruction-sheet (the identity morphism).

Question: But can one get to the essence of categorical results in this way?

Take Yoneda’s lemma. In the case of lego shapes it says that you know a shape once you know all morphisms into it from whatever shape.

For any coloured brick you’re given the number of ways this brick sits in that shape, so you know all the shape’s bricks. Then you may try for combination of two bricks, and so on. It sure looks like you’re going to be able to reconstruct the shape from all this info, but this quickly get rather messy.

But then, someone tells you the key argument in Yoneda’s proof: you only have to look for the shape to which the identity morphism is assigned. Bingo!

Question: Wasn’t your Alice interested in the ‘illegal’ or imaginary shapes?

Once you get to Yoneda, the rest follows routinely. You define presheaves on this category, figure out that you get a whole bunch of undesirable things, bring in Grothendieck topologies to be the policing agency weeding out that mess, and keep only the sheaves, which are exactly the desired imaginary shapes.

Question: Your book’s title is ‘Primes and other imaginary shapes’. How do you get from Lego shapes to prime numbers?

By the standard Gödelian trick: assign a prime number to each primitive coloured brick, and to a shape the product of the brick-primes.

That number is a sort of code of the shape. Shapes sharing the same code are made up from the same set of bricks.

Take the set of all strictly positive natural numbers partially ordered by divisibility, then this code is a functor from Lego shapes to numbers. If we extend this to imaginary shapes, we’ll rapidly end up at Connes’ arithmetic site, supernatural numbers, adeles and the recent realisation that the set of all prime numbers does have a geometric shape, but one with infinitely many dimensions.

Not sure yet how to include all of this, but hey, early days.

Question: So, shall we continue this interview at a later date?

No way, I’d better start writing.