No, this is not another timely post about the British Royal family.

It’s about Richard Borcherds’ “teapot test” for quantum computers.

A lot of money is being thrown at the quantum computing hype, causing people to leave academia for quantum computing firms. A recent example (hitting the press even in Belgium) being the move of Bob Coecke from Oxford University to Cambridge Quantum Computing.

Sure, quantum computing is an enticing idea, and we have fantastic quantum algorithms such as Shor’s factorisation algorithm and Grover’s search algorithm.

The (engineering) problem is building quantum computers with a large enough number of qubits, which is very difficult due to quantum decoherence. To an outsider it may appear that the number of qubits in a working quantum computer is growing at best linearly, if not logarithmic, in sharp contrast to Moore’s law for classical computers, stating that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles every two years.

Quantum computing evangelists assure us that this is nonsense, and that we should replace Moore’s law by Neven’s law claiming that the computing power of quantum computers will grow not just exponentially, but doubly exponentially!

What is behind these exaggerated claims?

In 2015 the NSA released a policy statement on the need for post-quantum cryptography. In the paper “A riddle wrapped in an enigma”, Neil Koblitz and Alfred Menezes carefully examined NSA’s possible strategies behind this assertion.

Can the NSA break PQC? Can the NSA break RSA? Does the NSA believes that RSA-3072 is much more quantum-resistant than ECC-256 and even ECC-384?, and so on.

Perhaps the most plausible of all explanations is this one : the NSA is using a diversion strategy aimed at Russia and China.

Suppose that the NSA believes that, although a large-scale quantum computer might eventually be built, it will be hugely expensive. From a cost standpoint it will be less analogous to Alan Turing’s bombe than to the Manhattan Project or the Apollo program, and it will be within the capabilities of only a small number of nation-states and huge corporations.

Suppose also that, in thinking about the somewhat adversarial relationship that still exists between the U.S. and both China and Russia, especially in the area of cybersecurity, the NSA asked itself “How did we win the Cold War? The main strategy was to goad the Soviet Union into an arms race that it could not afford, essentially bankrupting it. Their GNP was so much less than ours, what was a minor set-back for our economy was a major disaster for theirs. It was a great strategy. Let’s try it again.”

This brings us to the claim of quantum supremacy, that is, demonstrating that a programmable quantum device can solve a problem that no classical computer can solve in any feasible amount of time.

In 2019, Google claimed “to have reached quantum supremacy with an array of 54 qubits out of which 53 were functional, which were used to perform a series of operations in 200 seconds that would take a supercomputer about 10,000 years to complete”. In December 2020, a group based in USTC reached quantum supremacy by implementing a type of Boson sampling on 76 photons with their photonic quantum computer. They stated that to generate the number of samples the quantum computer generates in 20 seconds, a classical supercomputer would require 600 million years of computation.

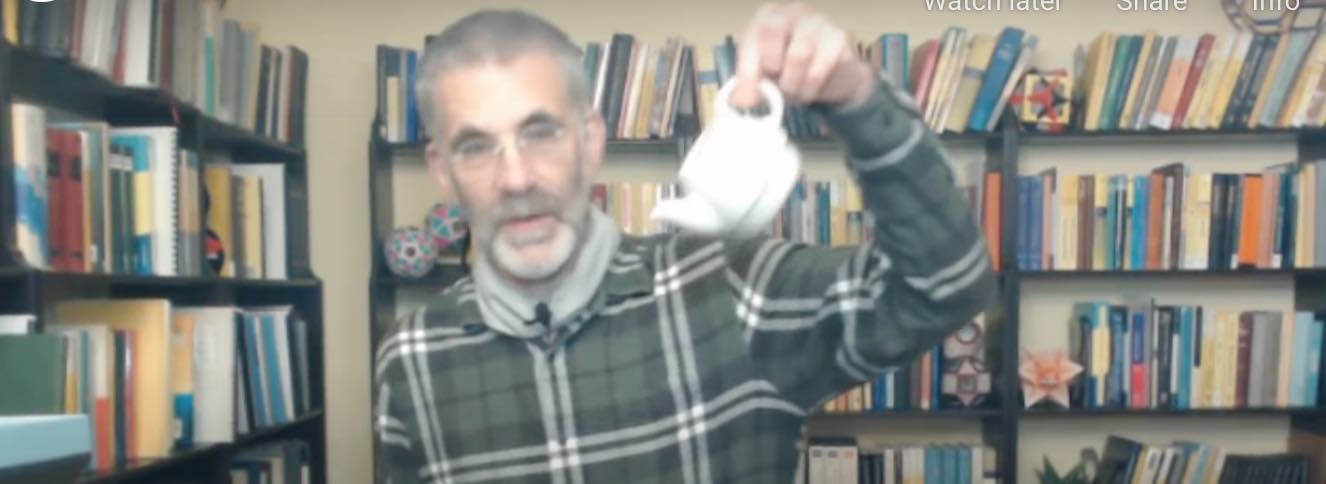

Richard Borcherds rants against the type of problems used to claim quantum ‘supremacy’. He proposes the ‘teapot problem’ which a teapot can solve instantaneously, but will be impossibly hard for classical (and even quantum) computers. That is, any teapot achieves ‘teapot supremacy’ over classical and quantum computers!

Another point of contention are the ‘real-life applications’ quantum computers are said to be used for. Probably he is referring to Volkswagen’s plan for traffic optimization with a D-Wave quantum computer in Lisbon.

“You could give these guys a time machine and all they’d use it for was going back to watch some episodes of some soap opera they missed”

Enjoy!

One Comment